Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Hills

Lakes

Dales

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

Saunterings: Walking in North-West England

Saunterings is a set of reflections based upon walks around the counties of Cumbria, Lancashire and

North Yorkshire in North-West England

(as defined in the Preamble).

Here is a list of all Saunterings so far.

If you'd like to give a comment, correction or update (all are very welcome) or to

be notified by email when a new item is posted - please send an email to johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com.

201. An Erratic Saunter from Austwick

The walk from Austwick to the Norber erratics will be familiar to any Dales walker – but

not to a five-year-old new to the Dales. So we took him (Cassius) and his parents

(our daughter and partner) on this walk.

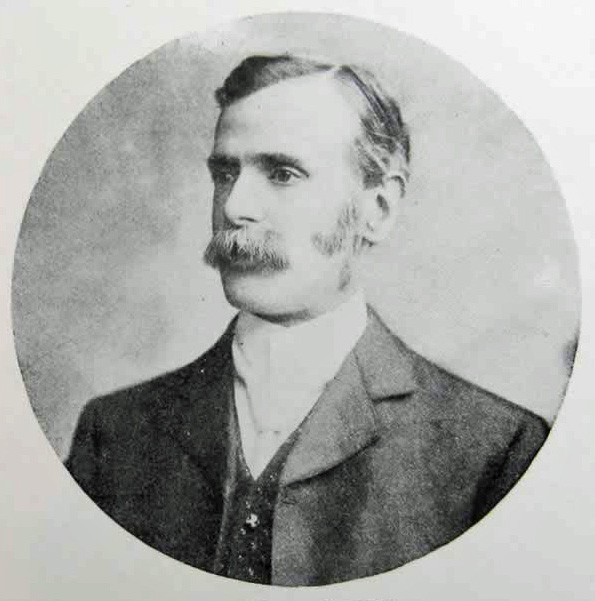

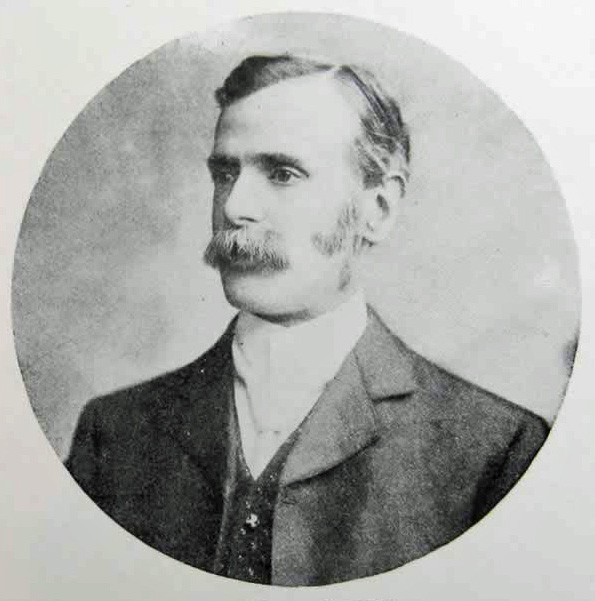

Harry Speight began Chapter XII of his classic book The Craven and North-West Yorkshire

Highlands (Speight 1895) with these words:

Harry Speight began Chapter XII of his classic book The Craven and North-West Yorkshire

Highlands (Speight 1895) with these words:

“Today there is a rich treat in store: a delightful walk, and just as long or as short,

as rough or as easy, as we like to make it. We intend to go through Austwick to Norber,

and where in England can you match the sight that is presented on the cliffs of Norber? It

is, as an open-air phenomenon of the operation of once Arctic Yorkshire, absolutely unrivalled.

To the non-geological mind, also, the scene is hardly less striking … Under the rosy aspects

of a fair day the whole scene is bewitching, and we feel that our first acquaintance with the

spot is, indeed, a case of love at first sight.”

Austwick must be a contender for best-kept village of the Dales. All house-owners, be it of

cottage or mansion, must maintain their house and garden with pride and skill or else be

shamed, shunned and sent to Coventry or at least to Ingleton. Perhaps Austwick still only

allows in suitable house-owners. It is an old tradition that Austwickians feigned gormlessness

to discourage anyone from outside moving in. For example, there’s the legend that

Austwick folk built a wall around cuckoos to prevent them leaving in the belief that their

departure brought the end of summer, not realising that cuckoos can fly over a wall.

Nowadays Austwick holds a Cuckoo Festival (it was the week before we visited). Speight

gave a number of examples of Austwickian stupidity – but without suggesting that it was

feigned.

We walked through Austwick and along the public footpath through someone’s garden

and then onto the fields, with distant views opening out of

the erratics speckling the hills of Norber and of Moughton across Crummackdale.

A distant view of the Norber erratics

A view across Crummackdale to Moughton

Eventually we reached the hundreds of boulders, some of considerable size, scattered about the

fields and tried to explain to Cassius why these stones are here (the glaciers having

transported them along Crummackdale to deposit here) but it takes some believing,

doesn’t it? After all, nobody believed it two hundred years ago.

Among the erratics

Exactly a hundred years ago two gentlemen, named P.E. Kendall and H.E. Wroot, explained that some of the

stones are balanced on pedestals because rainwater, which is slightly acidic, dissolves the

limestone (the ground rock), thereby lowering the general ground level, except where it is

protected under the greywacke erratics. It is an appealingly simple explanation that has been

repeated verbatim ever since.

Right: One of the Norber erratics. (The head that accidentally appears on the boulder's

shoulder is mine. I was sitting on a rock beyond.)

Right: One of the Norber erratics. (The head that accidentally appears on the boulder's

shoulder is mine. I was sitting on a rock beyond.)

However, research by Helen Goldie (Goldie, 2005) suggests that

several refinements are needed:

• According to the 1924 theory, the limestone

had eroded by as much as 50 cm since the boulders were deposited at the end of the Ice Age,

about 14,000 years ago. However, Goldie’s studies (and I don’t know the exact nature of her

studies) suggested that the normal erosion rate is 3 to 13 cm in 14,000 years.

• Perhaps the erratics were deposited

earlier – but in that case why didn’t later glaciers shift them away?

• Whatever the erosion rate at Norber was,

why is it that only a few of the erratics are on pedestals? They are the most

photogenic ones but they are not typical. Most of the boulders lie flat on the ground.

• In fact, many of the erratics that look

like they are on pedestals when viewed from below turn out to be resting on ground on their

higher side. The Norber erratics don’t lie in a flat field, where you might assume erosion

to be uniform – they lie on a slope, steeper at the top, with terraces. Rainwater

percolates downward and presumably causes more erosion at lower levels.

• The limestone surface is likely to

have been in a somewhat battered state at the end of the Ice Age. Some parts will have

been more fractured than others and therefore more liable to further erosion. Perhaps

the pedestalled erratics happen to have been deposited on particularly damaged limestone.

• Also rainwater dissolution is not the

only erosive force. In particular, when water within crevices freezes it will force

those crevices wider. Fractured limestone will be more liable to frost erosion. Even

the greywacke erratics can be split by frost.

• Another factor may be the animals (in

particular, the sheep) that shelter behind and under these stones. Their urine contains

more acid than any rainwater. This will presumably increase erosion, as will the fact

that the animal’s feet will remove grass and expose mud by the rocks.

We didn’t try to discuss any of this with Cassius. We had other

questions for him to ponder. For example, why is it that among all the green fields

we could see there were two that were bright yellow? In fact, they were fields left without

sheep in which buttercups were dominant. At least, I assume so – we saw a similar

yellow field on the way back to Austwick.

On the way we had good views of Robin Proctor’s Scar. A name on a map always

prompts the question: who? The legend is that one Robin Proctor rode his horse

over this cliff in fog, to their deaths. In case that seems apocryphal,

Johnson (2008) says that the Clapham Burial Register of 12 August 1667 records the

death of one Robert Procter ‘falling from a cliff at Norber’. (There’s no mention

of a horse but then horses aren’t usually recorded in Burial Registers.) If that’s him

the map should spell his name correctly.

Robin Proctor's Scar (to the left) and Nappa Scars (to the right)

I have made it a rule not to discuss in these Saunterings any hostelry I might happen to

visit on these outings – because I don’t visit enough of them to make fair judgements

and, in any case, the turnover of staff soon renders any judgement invalid. I’ll just

advise that if you visit the Game Cock don’t have supper in the back garden during midge season.

They will have as much of a meal as you.

I don’t know if our five-year-old experienced love at first sight but he enjoyed the scramble.

Date: June 1st 2024

Start: SD768683, road by The Traddock, Austwick (Map: OL2)

Route: NW, NE on Main Street , N on Townhead Lane, N on fields across

Thwaite Lane and Norber Sike – Crummack Lane – W, NW among boulders, S, SE – Thwaite Lane – S,

SW – Game Cock – SE

Distance: 4 miles; Ascent: 150 metres

Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Hills

Lakes

Dales

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

© John Self, Drakkar Press, 2018-

Top photo: Rainbow over Kisdon in Swaledale;

Bottom photo: Ullswater

Harry Speight began Chapter XII of his classic book The Craven and North-West Yorkshire

Highlands (Speight 1895) with these words:

Harry Speight began Chapter XII of his classic book The Craven and North-West Yorkshire

Highlands (Speight 1895) with these words:

Right: One of the Norber erratics. (The head that accidentally appears on the boulder's

shoulder is mine. I was sitting on a rock beyond.)

Right: One of the Norber erratics. (The head that accidentally appears on the boulder's

shoulder is mine. I was sitting on a rock beyond.)