Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

Saunterings: Walking in North-West England

Saunterings is a set of reflections based upon walks around the counties of Cumbria, Lancashire and

North Yorkshire in North-West England

(as defined in the Preamble).

Here is a list of all Saunterings so far.

If you'd like to give a comment, correction or update (all are very welcome) or to

be notified by email when a new item is posted - please send an email to johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com.

11. The Struggle over Boulsworth Hill

I set off to walk from Colne up Boulsworth Hill, following in the footsteps of mill-workers of over a century ago.

Colne was the birthplace in the 1890s of the

Co-operative Holidays Association (CHA), a fact that will not mean

much to most ramblers of North-West England today. We have been led to believe that we owe our modern right

and keenness to walk on the mountains and moors entirely to the influence of William Wordsworth and fellow

poets of the Lake District. It was they who changed our cultural perception of mountains. No longer should

we regard the mountains with trepidation but we should walk upon them in order to appreciate their lustrous scenery.

So pervasive was Wordsworth’s influence that for a time the region was commonly called Wordsworthshire.

Boulsworth Hill from near Trawden, on the way from Colne

However, the struggle for access to the mountains and moors was fought not in the Lake District but

in the South Pennines and the Peak District, in industrial towns such as Colne. Landowners in the

Lake District had always accepted that people could walk on the mountains, as they knew that very

few people would choose to do so. A few poets tripping about, polishing their triplets, did not

change that. Even if they did inspire others to come to see the daffodils and the mountains,

there were not many people within easy access of the Lake District to do so.

It was different in the Pennines. By that time, the 19th century, millions of working people had moved from rural areas to live and work in the grit and grime of industrial cities such as Manchester and Sheffield. They could not just up sticks and move to the Lake District and spend days walking around it, as Wordsworth and friends did. However, many of those workers felt an equal, if not greater, need for fresh open air and fine scenery – and probably appreciated it as much even if they didn’t write poems about it. The many ‘rambling clubs’ that formed in industrial cities to help worker-walkers into the countryside emphasised fellowship – the chance to walk and talk with others away from the noise of factories – rather than wandering lonely as a cloud. This communal aspect was the foundation for the famous mass trespasses that played a key role in changing access legislation (eventually).

From Boulsworth Hill, looking south.

From Boulsworth Hill, looking south.

The CHA was a leading player in this movement but with a slightly different emphasis. It welcomed male and female

members, which was somewhat controversial for the time. It also had a broader aim than just rambling, providing what would

nowadays be called ‘adventure holidays’. CHA was founded by Thomas Leonard, who went on to help establish the Youth Hostels

Association and the Ramblers’ Association. There is, a touch ironically perhaps, a

memorial to him, as a pioneer of the

open-air movement, on Catbells near Derwent Water. Colne does not seem to remember Leonard at all – but then Leonard did

refer to Colne as a “bleak upland township” in his memoirs.

Would-be ramblers were not asking for a new right. They were asking for the restoration of the right to walk freely on uncultivated land, on common land, and on centuries-old rights of way – a right that their ancestors had taken for granted. This right was disappearing for two reasons. First, the many Enclosure Acts had led to the consolidation of land ownership within the hands of a relatively few wealthy people. Those owners increasingly felt that, just as they wouldn’t allow anyone to walk through the corridors of their mansions, so they wouldn’t allow them to walk across their fields. Secondly, the uncultivated land that previously had been worthless – and therefore not made worth less by allowing anyone to walk on it – had now become valuable, because people were keen to pay handsomely for the fun of killing grouse and deer.

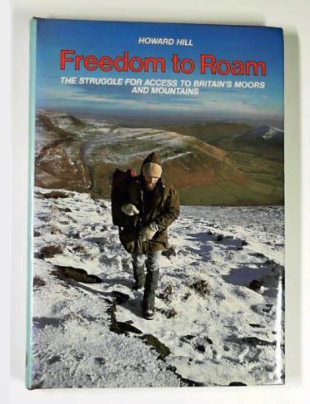

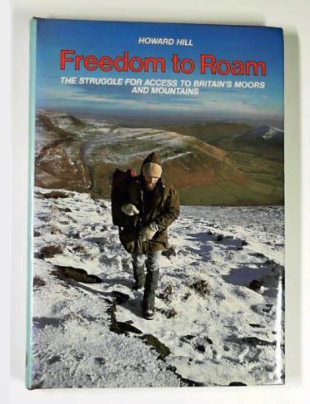

The struggle for access was extraordinarily protracted, as described by Hill (1980). The first Access to Mountains Bill was in 1884. A solution acceptable to ramblers was not found until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000. The thousands of worker-walkers were up against the ruling landed gentry, the views of which can be gauged from comments in 1932 by the Duke of Atholl, who owned 140,000 acres of deer forests. He considered the then Access to Mountains Bill to be “a crank’s measure, which would injure farming, sport [by which he meant deer-killing], and rateable values” and that “there was not the slightest desire on the part of the general public to go on these hills”.

The struggle for access was extraordinarily protracted, as described by Hill (1980). The first Access to Mountains Bill was in 1884. A solution acceptable to ramblers was not found until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000. The thousands of worker-walkers were up against the ruling landed gentry, the views of which can be gauged from comments in 1932 by the Duke of Atholl, who owned 140,000 acres of deer forests. He considered the then Access to Mountains Bill to be “a crank’s measure, which would injure farming, sport [by which he meant deer-killing], and rateable values” and that “there was not the slightest desire on the part of the general public to go on these hills”.

Concessions were extracted like very reluctant bad teeth. Moor owners might concede access – but only outside the nesting and shooting seasons – which they then defined to be almost the whole year. Sometimes there was a ludicrous aspect to the proposed access agreements. For example, a proposal for access to Rombalds Moor, which includes Ilkley Moor, included a clause that there must be no singing on the moor. If there is one moor that we should be allowed to sing on then it is surely Ilkley Moor.

If an Access to Mountains Bill ever became an Act it was only after it had passed through lengthy parliamentary

committee discussions to emasculate it. For example, the eventual

1939 Act bore little resemblance to the original Bill.

It ended up providing no access rights whatsoever. On the other hand, it did somehow come to include a ‘trespass clause’

that for the first time ever in England made it a criminal offence merely to be on wild moorland. Moreover, it gave

gamekeepers the legal right to demand names and addresses of anyone found there, with those refusing to give them being

liable to a fine of £5. The legacy of this rather astonishing assumption that gamekeepers were part of the law enforcement

process, and hence above the law themselves, is with us today, causing difficulties in tackling wildlife crime.

There was therefore a class and political dimension to the struggle, a dimension that did not trouble Wordsworth and his friends much. They were relatively well-to-do and no doubt mingled with the higher strata of Lake District society. The factory worker never met the Duke of Wherever who owned the local moors. As the ‘co-operative’ in CHA’s title indicates, there were affiliations with the growing labour and socialist movements. Indeed, some of the activists were known to be communists, which did not help their cause when, as in the Kinder Scout mass trespass of 1932, they were charged with assaulting a gamekeeper.

Boulsworth Hill, near Colne, is an interesting case study, as detailed by Hill (1980). Today’s OS map for Boulsworth Hill shows no green dotted lines denoting public footpaths. There never were any. There are plenty of public footpaths heading from Colne but they all end abruptly at the foot of the moor. I headed that way myself but, as Colne and Trawden have more or less merged now, it no doubt took me longer to reach open countryside than it used to.

In 1956 the councils of Colne, Keighley and Trawden, infiltrated as they were by local landowners, resisted pressure

to allow access to Boulsworth Hill, arguing at a public enquiry that the public should be content to gaze at it. No doubt,

some intrepid Colne walkers trespassed thereon. In 1956 they may have hoped that they wouldn’t need to trespass for much

longer because the County Council was obliged under the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act to impose

an access order. It was in fact the first one ever issued. However, it took another 22 years before a path to the summit

was opened, and this was on water authority land, not on land for shooting grouse. Today, of course, it is all open access land.

I walked up to Lad Law (517 metres), the highest point of Boulsworth Hill. Some might think that the view thereby

attained is somewhat desolate. Ahead, to the south, there are dull heather moors enlivened only by occasional millstone

grit outcrops (shown above). Behind, however, to the west, north and east, there are fine panoramas, although not as clear for me as they can be.

Pendle was prominent, but the outline of Ingleborough was only dimly discernible and the promised sight of Blackpool

Tower non-existent.

Colne and Trawden from Lad Law on Boulsworth Hill

Having conquered Boulsworth Hill and paid my respects to the pioneering trespassers, I gave myself a bonus by heading for

Wycoller, a tiny, tidy village known to visitors for the ruined

Wycoller Hall (which, frankly, didn’t interest me much)

and three old bridges: in the order met on this walk, a ‘clam’ bridge, a clapper bridge, and a packhorse bridge.

The first two of these are not that exciting

to look at, being just great slabs across the beck, but the packhorse bridge is charming and skilfully built. It has two

arches, a width of a mere 66 centimetres and parapets only 25 centimetres high. According to Hinchliffe (1994), it has survived 700-800 years.

In the circumstances, I think we can forgive the slightly wonky brow of the right eye.

The Wycoller packhorse bridge

Date: May 10th 2018

Start: SD912388, Trawden (Map: OL21)

Route: S, SE – Lodge Moss Farm, Boulsworth Dyke Farm – SW, SE – Lad Law – NE – Saucer Hole –

N – Saucer Hill Clough – NW through Turnhole Clough – Wycoller – W on road, S, W, S – Trawden

Distance: 8 miles; Ascent: 355 metres

Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

© John Self, Drakkar Press, 2018-

Top photo: The western Howgills from Dillicar;

Bottom photo: Blencathra from Great Mell Fell

From Boulsworth Hill, looking south.

From Boulsworth Hill, looking south.

The struggle for access was extraordinarily protracted, as described by Hill (1980). The first Access to Mountains Bill was in 1884. A solution acceptable to ramblers was not found until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000. The thousands of worker-walkers were up against the ruling landed gentry, the views of which can be gauged from comments in 1932 by the Duke of Atholl, who owned 140,000 acres of deer forests. He considered the then Access to Mountains Bill to be “a crank’s measure, which would injure farming, sport [by which he meant deer-killing], and rateable values” and that “there was not the slightest desire on the part of the general public to go on these hills”.

The struggle for access was extraordinarily protracted, as described by Hill (1980). The first Access to Mountains Bill was in 1884. A solution acceptable to ramblers was not found until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000. The thousands of worker-walkers were up against the ruling landed gentry, the views of which can be gauged from comments in 1932 by the Duke of Atholl, who owned 140,000 acres of deer forests. He considered the then Access to Mountains Bill to be “a crank’s measure, which would injure farming, sport [by which he meant deer-killing], and rateable values” and that “there was not the slightest desire on the part of the general public to go on these hills”.