Home Preamble Index Areas References Me

Swaledale, looking downriver, with the River Swale hidden in the trees to the left and with Muker hidden to the right

Kisdon itself is an isolated hill reaching 499 metres. It forms a rough triangle of high ground, with the small villages of Muker, Keld and Thwaite at its corners. Along the sides of the triangle are the River Swale to the east, the small stream of Skeb Skeugh to the west, where the Swale used to flow before being diverted during the last Ice Age, and Straw Beck to the south.

Swaledale, looking upriver, with the River Swale to the left and with Swinner Gill ahead

It also gathers the water from Swinner Gill, a ravine to the north, up which we walked next on a thin path through young bracken. The path is high above the beck, which had sufficient water to create a series of attractive waterfalls. The signs of the old lead mines are gradually disappearing. It is no longer a grim, barren valley, as the spoil heaps become overgrown and the cliffs seem more natural. We didn’t locate the footbridge shown on the map but on closer inspection of the map now I suspect that we didn’t go quite far enough up the valley. The fact that there was no need for a footbridge had lured us to cross the beck too early. Not finding the footbridge meant that we didn’t immediately find the footpath on the northern slopes that leads to it. So we scrambled up through the bracken and rocks until we eventually reached the path. We always like a bit of off-piste scrambling to enliven our outings.

Swinner Gill

Passing the ruins of Crackpot Hall, we joined the wide, well-worn path, with a good number of sunny summer Sunday walkers, to reach Keld. The name Crackpot was originally Crakepot, from the old English word for crow. The hall was built as a shooting lodge and then became a farm until literally undermined by all the mining hereabouts. Now its ruins enhance a photogenic view along the Swale valley towards Muker and across to the hill of Kisdon.

Crackpot Hall and Swaledale, with Kisdon to the right

Keld is a more scattered community than Muker, with most of the houses lying on a side-road that drops down from the B6270 to the river. From Keld we walked south on a path that crossed countless fields, small enough that at each wall we could usually see the stile in the wall ahead. In any case, the path has enough walkers to make the direction clear on the ground. It passed several fine barns and provided excellent views of Kisdon, eventually reaching the third corner of our triangle, the village of Thwaite. Here we had a decision to make: should we walk the two miles through more fields back to Muker or should we pause for a tea break at the Thwaite tearoom and catch the bus from the corner of the Buttertubs road?

Thwaite, with Kisdon to the right

It was a hot day and the drink was very welcome. I had looked at the website of the Kearton Country Hotel and tearoom beforehand and had been surprised not to find any explanation there of its name. So I asked the man at the bar and was relieved that he knew that it was named after the Kearton brothers, pioneer photographers and naturalists who were born in Thwaite. However, I sensed that he was somewhat jaundiced about this association. He waved towards a row of the Keartons’ books high on a shelf, inaccessible to all, and mentioned that there were portraits in the hotel lounge. I went to have a look. There were indeed two portraits but not really much about their work. He referred to the ‘bandwagon’ of people who have lately become interested in the Keartons as a result of David Attenborough saying that they had been an inspiration to him in his younger days. I suppose I was on that bandwagon so I retreated to our table outside.

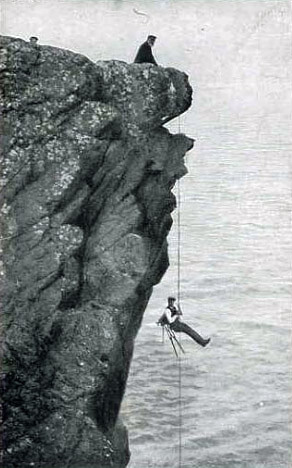

Nowadays every wildlife TV programme ends with a section showing us the lengthy, harrowing ordeals

suffered by the film crew while struggling to record, say, fifteen seconds of a snow leopard. However,

these crews are lucky that they weren’t working in about 1900 when cameras were much heavier, noisier

and slower. The Kearton brothers, Richard (1862-1928) and Cherry (1871-1940), had to

invent many techniques to enable them to photograph the natural world. For example, they developed an

elongated tripod that required one of the brothers to stand on the shoulders of the other to

take photographs. They also had a dead ox hollowed out by a taxidermist so that they could position

it in a field and then crawl into the belly of the ox, with a camera lens poking through its head.

They called this object their ‘stuffed ox’, although it wasn’t stuffed until one of them crawled inside.

Judging from their

Wild Nature's Ways

(1903), the word ‘hide’ was not yet used for a hidden

observation position – otherwise they might have called it an ox-hide.

Nowadays every wildlife TV programme ends with a section showing us the lengthy, harrowing ordeals

suffered by the film crew while struggling to record, say, fifteen seconds of a snow leopard. However,

these crews are lucky that they weren’t working in about 1900 when cameras were much heavier, noisier

and slower. The Kearton brothers, Richard (1862-1928) and Cherry (1871-1940), had to

invent many techniques to enable them to photograph the natural world. For example, they developed an

elongated tripod that required one of the brothers to stand on the shoulders of the other to

take photographs. They also had a dead ox hollowed out by a taxidermist so that they could position

it in a field and then crawl into the belly of the ox, with a camera lens poking through its head.

They called this object their ‘stuffed ox’, although it wasn’t stuffed until one of them crawled inside.

Judging from their

Wild Nature's Ways

(1903), the word ‘hide’ was not yet used for a hidden

observation position – otherwise they might have called it an ox-hide.

Home Preamble Index Areas References Me

© John Self, 2018-

Top photo: The western Howgills from Dillicar; Bottom photo: Blencathra from Great Mell Fell