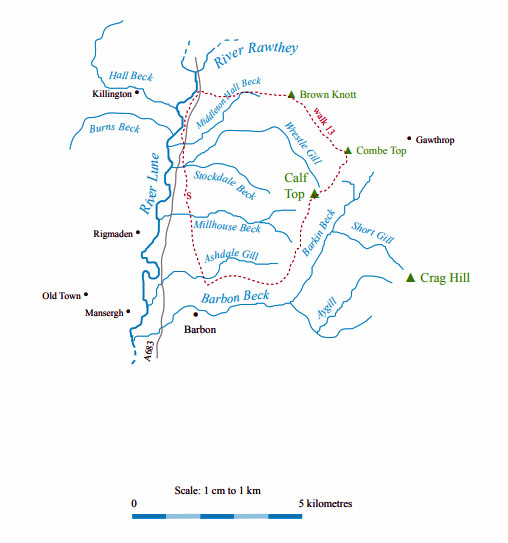

Walk 13: Middleton Fell

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: A lay-by on the east side of the A683, just north of where it swings away from the line of the Roman road, at

Jordan Lane (631892).

Walk south a short distance and cross a field to join the road east to Fellside (demolished and rebuilt in 2007). Beyond

Fellside you are on the open fell and will probably see nobody for the next three hours or so. There are many tracks but follow

one east to reach the ridge near Brown Knott, for a view of Sedbergh and the Howgills beyond.

Follow the ridge wall southeast. Above Combe Scar there is a new slab stile in the wall that is worth crossing for a short

detour to peek at the scar and gain a bird’s-eye view of Dent. Return by the stile.

Continue round the ridge, with a continuously evolving panorama of hills, eventually heading southwest, to reach Calf Top.

From Calf Top, turn at right angles right, walking slightly north of west. It is important to take the correct ridge. Aim for the aerial

that can be seen across the Lune valley on Park Hill. You need to reach the wall where there is a thin wood alongside Brow Gill.

(If you swing too far south you may be tempted to head for Mill House, where the OS map shows an apparent exit from CRoW

land. There are however a few metres of adamantly private land separating CRoW land from the public footpath. Which is a pity.

If you go too far north you may as well continue back the way you came, past Fellside.)

Follow the wall north for 200m to reach a gate (at 642868) where a sign says that a permissive path begins. This path goes

by Brow Gill, north along the old railway line for 300m, and then by Stockdale Beck to reach the quiet High Road.

Walk north for 500m to Middleton Hall Bridge, with the hall to your right. Cross the A683 and take the path across the field

and between Low Waterside and the Lune. Continue on this path, which eventually rises through a wood to the A683.

[Update: The walk description here does not correspond to the red-dotted

walk shown on the map at the end of this chapter. Sorry about that. I found out about the permissive path

just before the book was published and changed the walk description to use it but forgot to change the red dots as well.

For the walk as described the start point is at the north-west corner of the red dots and the red dots

should proceed west, not south, from Calf Top. Unfortunately I am no longer able to change the map.]

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk to Brown Knott. Now head southwest over pathless ground to reach the wall corner

where Luge Gill leaves CRoW land. Follow the wall at the boundary of CRoW land for 1.5 km until you reach the gate (at

642868) where the sign indicates the start of the permissive path. Then return to the lay-by as for the long walk.

Left: Orchid on New Park, Killington

Left: Orchid on New Park, Killington

Right: Killington Hall

Right: Killington Hall

Left: High Stockdale Bridge

Left: High Stockdale Bridge

Left: The Roman milestone near Hawking Hall

Left: The Roman milestone near Hawking Hall

Right: Kitmere

Right: Kitmere

Right: Terrybank Tarn

Right: Terrybank Tarn

Right: The head of Barbondale

Right: The head of Barbondale

Left: The wood near Barbon Manor

Left: The wood near Barbon Manor

Right: St Bartholomew’s Church, Barbon

Right: St Bartholomew’s Church, Barbon