The Land of the Lune

Chapter 5: Lower Rawtheydale and Dentdale

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Upper Rawtheydale)

The Next Chapter (Middleton Fell)

Deepdale and Dentdale

The Rawthey from the Clough ...

Right: Stone Hall, near Sedbergh

Right: Stone Hall, near Sedbergh

The Clough, having travelled much the same

distance as the Rawthey up to this point, almost

doubles the size of the Rawthey, which now

changes character and relaxes into a double bed, as

it were, some 50m wide. Opposite the junction is the

old Stone Hall, with a three-storeyed porch and large

round chimneys, the latter also to be seen at nearby

Hollin Hill. I have not seen such chimneys elsewhere

in Loyne and, being an inquisitive soul, I have tried to

find an explanation. I understand that they are ‘Flemish

chimneys’ and that there is a preponderance of similar

chimneys in Pembrokeshire, for some reason, and

presumably also in Flanders. Why they are here I have

been unable to discover.

On the outskirts of Sedbergh the Rawthey is joined

by Settlebeck Gill, which runs past the earthwork

remains of the Castlehaw motte and bailey. The motte,

at 9m high, must have been a good observation post. The

remains are on private land but seem in good shape, as

can be best seen from the slopes of Winder.

Sedbergh oozes contentment, and why not? Basking

below Winder, it gains strength from its one thousand

years of history, serenity from the playing fields of the

five-hundred-year-old school, and self-confidence from

its newfound status as a ‘book town’.

Left: Welcome to Sedbergh

Left: Welcome to Sedbergh

Sedbergh was mentioned in the

Domesday Book of 1086 and Castlehaw

confirms its strategic importance, lying

near the meeting of four rivers, the Lune,

Rawthey, Clough and Dee. A market

charter was granted in 1251. St Andrews

Church has a Norman doorway and

lists vicars back to 1350 but was largely

rebuilt in 1886 (although the clock has a

date of 1866, for some reason). Within

the church are several plaques to local

notables, including John Dawson, an

eminent mathematician, born in Garsdale

and “beloved for his amiable simplicity of

character.” My favourite is that of the Rev.

Posthumus Wharton, who was headmaster

of Sedbergh School from 1674 to 1706.

Sedbergh School was established as a

chantry school in 1525 by Roger Lupton,

provost of Eton and born in the parish of

Sedbergh. After the Dissolution of the

Monasteries (1539), it was re-established as a grammar

school in 1551. The school has not always flourished:

in 1865, when it had only ten pupils, an inspection

considered that “it simply cumbers the ground”.

Amongst recent alumni are the rugby stars, Will Carling

and Will Greenwood. Although Sedbergh School is not

in the top division of independent schools, it is central to

Sedbergh’s image.

This image perhaps helped Sedbergh to persuade

itself to become England’s first book town in 2005

(the pioneering book town, Hay-on-Wye, being just

in Wales). Book town status is not formally defined:

what makes a place a book town is simply a decision

to proclaim itself one. By convention, a book town is a

small town in which little else happens apart from the

selling of old books. This description may deter non-bibliophiles but presumably Sedbergh hopes that overall

a boost will be given to the local economy and culture.

The obligatory Book Festival takes place in the autumn

and a more innovative Festival of Ideas in the summer,

although the latter lapsed in 2009, which is a shame as

we are all in need of good ideas.

Sedbergh’s self-image is also reflected in its

participation in 2004 in the BBC TV programme The

Town that Wants a Twin in which, over twelve long

episodes, Sedbergh auditioned four towns for the honour

of becoming Sedbergh’s twin. The citizens of Sedbergh

duly voted for Zrece of Slovenia. This one-way process

does not seem to reflect the spirit of twinning as an equal

partnership.

There are pleasant, well-used paths on both banks

of the Rawthey. At Millthrop Bridge we rejoin the Dales

Way, which follows the Rawthey for 4km before veering

north to join the Lune. As you might expect of a village

whose sign proudly calls it a “hamlet”, Millthrop itself

is a set of cottages too pretty for words – at least, any

words of mine.

After a further kilometre, the Rawthey goes over

a weir that was used to power Birks Mill for cotton

spinning and then, after a bend, is joined by the River

Dee from the south.

Sedbergh, with Winder, Arant Haw and Crook behind

The River Dee

The River Dee rises on Blea Moor and runs 20km

through Dentdale, many people’s favourite of the

Yorkshire Dales, even though it is now in Cumbria. Only

the very highest of the headwaters of the Dee on Blea

Moor are in North Yorkshire.

Right: Artengill Viaduct

Right: Artengill Viaduct

There is only one feature of note on Blea Moor and

that we cannot see: the tunnel that runs for 2.5km under

it. This is for the Settle-Carlisle line, which continues

on the flanks of Wold Fell and Great Knoutberry Hill

over the impressive viaducts at Dent Head and Arten

Gill, built from 1870 to 1875. They have ten and eleven

arches, respectively, and are both over 30m high. Their

construction, in this high and remote terrain, was difficult

and hazardous. On one occasion, a flood caused by 6cm

of rain in 45 minutes drowned two people, buried a

horse and wagon in debris, and washed away several

bridges. Earlier, according to David Boulton’s booklet

Discovering Upper Dentdale, in 1752 an avalanche

killed seven people, which, I believe, makes that the

second worst avalanche in the United Kingdom. So,

although it is likely to be pastoral tranquillity when we

visit, the weather can be wild here.

The two viaducts are built of ‘Dent marble’, which

is actually a dark limestone. The marble was mined

locally until the 1920s and prepared at Stone House,

near Arten Gill. It was valued for ornamental masonry,

such as luxury fireplaces – indeed, being so valued, it

seems strange that such huge volumes were used in the

viaducts. No doubt, the convenience of being to hand

was the main factor. The previously rough track by Arten

Gill has recently been renovated to form part of the 350-mile Pennine Bridleway National Trail.

Dent Station is 2km north of Artengill Viaduct and

is a tribute to the engineer’s faith in the energy of the

residents in Dentdale. It is 7km from Dent itself and

the final kilometre up from Lea Yeat is very steep. The

station platform has a notice saying that, at 350m, it is

“the highest mainline station in England”. It is pleasing

that someone at least regards the Settle-Carlisle line as

a main line. The station is surprisingly neat, considering

the weather conditions, painted dark red, and gives fine

views into Dentdale. The old station building can be

rented for holiday accommodation, so you could enjoy

the view through its windows, obscured a little by “eciffo

tekcit” and “moor gnitiaw seidal”. The converted station

is now the proud recipient of a North West Tourism and

Leisure Award.

The road passing Dent Station is called the Coal

Road and the stretch on Galloway Gate is pockmarked

with disused coal pits. Coal mining stopped as soon as the

railway existed to deliver coal more cheaply. The name

of Galloway Gate tells us that it used to be a drove road.

It is hard today to imagine this clamour of activities high

up, at over 500m, on the now lonely and quiet moor.

Cowgill Beck runs from the area of the coal pits,

through Dodderham Moss, one of the conifer plantations

that disfigure Dentdale, past the entrance to Risehill

Tunnel on the Settle-Carlisle line, to join the Dee at

Cowgill. The foundation stone of Cowgill Chapel was

laid in 1837 by Dentdale’s most famous son, Adam

Sedgwick, who, although living in Cambridge, continued

to keep a fatherly eye on his chapel. Thirty years later,

Sedgwick led a campaign to parliament to have the name

of Cowgill Chapel restored when the curate changed it

to Kirkthwaite Chapel. He preferred the unpretentious

‘Cowgill’ and was angry at the misspelling of Kirthwaite,

the old name for the region. The curate, however, was

not to blame: the 1852 OS map has “Kirkthwaite”.

Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873) was born in Dent and spent

much of his youth scrambling over the fells collecting

rocks and fossils. From Sedbergh School he went to Trinity

College, Cambridge, where he became a fellow. He was

ordained in 1817, thus following the family tradition, as

evidenced by the many memorials in the Dent church.

In 1818, despite having no recognised experience of

fieldwork, he became Professor of Geology.

He duly set out to become a proper geologist. His

studies of the complex geology of the Lake District led to

a pioneering publication in 1835. He discovered the Dent

Fault, and the Sedgwick Trail in Garsdale is named after

him. He became president of the Geological Society of

London and organised many scientific activities.

Inevitably, he became embroiled in scientific debates

of the time, such as the Great Devonian Controversy,

concerning the mapping and interpretation of various

geological strata. Of more resonance today is his

disagreement with his ex-student Darwin over his theory

of evolution. To the author of Origin of Species, Sedgwick

wrote “I have read your book with more pain than pleasure.

Parts of it I admired greatly; parts I laughed at until my sides

were sore; other parts I read with absolute sorrow; because

I think them utterly false and grievously mischievous”.

What grieved him was the removal of the guiding hand of

God from the process of natural selection, which he could

not accept. This view endears him today to creationists,

although unlike many of them he did, as a geologist, accept

that the Earth was extremely old.

Sedgwick retained the warm-spirited generosity

attributable to his Dentdale upbringing. Although he lived

in Cambridge all his working life, he maintained his links

to Dent and in 1868 wrote A Memorial by the Trustees

of Cowgill Chapel that gives one of the best pictures of

Dentdale life at the time.

The Top 10 people in Loyne

Before you complain, yes, they are all men. Nominations of women are very welcome.

1. Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873), Dent, geologist.

2. John Fleming (1849-1945), Lancaster, electrical engineer.

3. Richard Owen (1804-1892), Lancaster, palaeontologist.

4. John L. Austin (1911-1960), Lancaster, philosopher.

5. William Whewell (1794-1866), Lancaster,

philosopher and scientist. (Whewell is said to have invented the word ‘scientist’.)

6. Reginald Farrer (1880-1920), Clapham, botanist.

7. James Williamson (1842-1930), the son, Lancaster, businessman and politician.

8. John Lingard (1771-1851), Hornby, Catholic historian.

9. William Sturgeon (1783-1850), Whittington, physicist.

10. Laurence Binyon (1869-1943), Burton-in-Lonsdale, poet.

In the valley the River Dee gathers the waters than

run steeply off the fells through deep gorges and cascades,

and proceeds serenely down its upper reaches from Dent

Head to Cowgill. The riverbed is mostly flat rock, which

the river seems to shimmer over, with occasional ledges

producing little waterfalls and, at Scow, a reasonably

large one.

Right: Ibbeth Peril

Right: Ibbeth Peril

As the Dee turns west, it enters a more turbulent

phase. If you investigate the river closely – for example,

around the Ibbeth Peril waterfall and along the stretch

between Lenny’s Leap, where the river narrows to run

in a gully 50cm wide, and Tommy Bridge – you may

notice that the volume of water does not always increase

as it flows west. Some of the clefts and holes that can be

seen in the limestone walls and bed of the gorge are large

enough to form caves, through which the river tends

to disappear. As you walk on the north bank towards

Tommy Bridge, water can be seen entering the Dee from

below the south bank, with no beck apparent in the fields

above.

The area forms the Upper Dentdale Cave System,

a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is one of the best

examples of a cave system that had developed beneath the

valley floor and that has been broken into by the modern

river eroding its bed. The system extends for 1.7km in a

narrow band under the present river and includes a 30m

by 60m chamber. Under normal conditions, most of the

river is now underground and is modifying pre-existing

caves. The cave system is complex and needs experts

to investigate and interpret but, on the surface, we see

holes and caves, with water flowing into or out of some

of them.

Above the level of the floodplain Dentdale is lined

with farmsteads every 200m or so on both sides. Most

of the farmsteads are still actively farming, giving a

predominantly rural feel to the valley. Some have been

converted to holiday homes and some are derelict. The

most interesting of the latter is Gibbs Hall – a ruin now

surrounded by its offspring: Gibbs Hall Cottage, Little

Gibbs Hall and Gibbs Hall Barn. From the road two

windows with chamfered mullions and arched lintels

can be seen.

On the opposite bank is the imposing Whernside

Manor, originally and more properly called West

House, as it is not a manor house. It was built by the

Sill family, who not only became rich by exploiting

slaves in Jamaica but also employed slaves in Dentdale,

a practice continued long after they were supposed to be

emancipated. This is now a matter of shame for locals

although I overheard one in the Sun Inn who was either

proud that Dentdale had had the last slaves in England

or had imbibed too much of the esteemed local ale from

the Dent Brewery at Cowgill.

The name of Whernside Manor reminds us that the

Dee has been flowing around the broad northern slopes

of Whernside, the highest point (736m) of the Yorkshire

Dales, and gathering the becks that flow north from it.

Despite its height, there are few impressive views of

Whernside, the one from Dent across Deepdale being

as good as any. It is a ridge rather than a plateau or peak

and has few of the high-level cliffs that provide such

distinctive profiles to other Dales peaks.

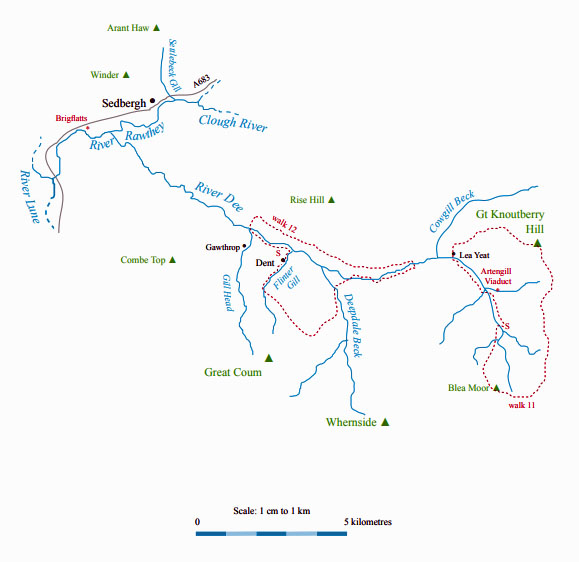

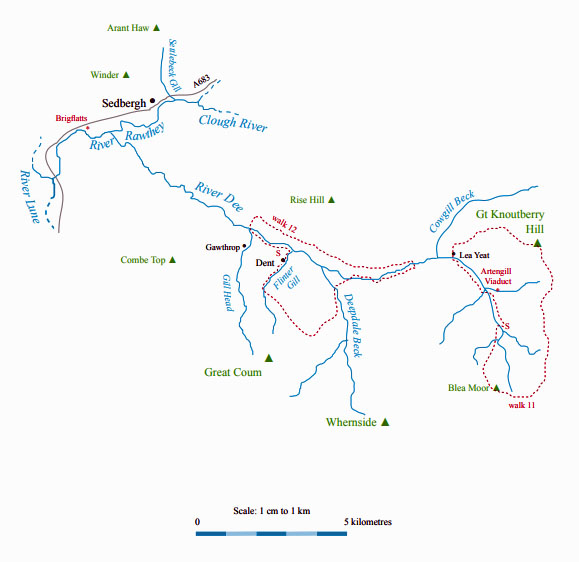

Walk 11: Upper Dentdale and Great Knoutberry Hill

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: By Dent Head Viaduct (777845).

Some of this walk is on roads, but they are quiet ones and the easy walking there compensates for the difficult going

elsewhere. From Dent Head Viaduct walk on the road 200m northwest to Bridge End Cottage and then take the footpath opposite

that leads back to Dent Head Farm and past the entrance to Bleamoor Tunnel. Once out of the plantation and past the air shaft

cut across to the trig point on Blea Moor (535m) for a good view of Whernside and of the Settle-Carlisle railway line far below

behind you.

Make your way east as best you can (there is no path) to join the Dales Way at Blake Rake Road. Follow the way north by

Stoops Moss to reach the road. Turn right and take the path north that continues past Wold Fell (resist the temptation to conquer

Wold Fell: there is no identifiable top and walking is unpleasantly uneven, being on grassed-over limestone clints) to reach the

bridleway at the top of Arten Gill at the point opposite the track that leads to the Galloway Gate.

Turn right for 200m to take the waymarked path that follows the wall to the top of Great Knoutberry Hill (672m), from

where the peaks of Pen-y-Ghent, Ingleborough and Whernside are wonderfully arrayed and the outline of Wild Boar Fell is

impressive. Widdale Tarns can be seen to the north. Continue west by the fence past a family of cairns to the recently-improved

bridleway.

Follow this track for 600m north and then take the Coal Road west, having a look at the neat Dent Station on the way. At

Lea Yeat Bridge note the Cowgill Institute, a Quaker meetinghouse from 1702. Many farmsteads here served as meetinghouses

in the years after George Fox visited in 1652, on his way to speak at Fox’s Pulpit. Cross the River Dee and turn left to follow the

road back to Dent Head Viaduct, past (or not, if you wish) the Sportsman’s Inn, a 17th century establishment that regards grouse

shooters as sportsmen. If energy permits, a detour to look at Artengill Viaduct is worth it.

Short walk variation: There are two obvious shorter walks. One is to follow the long walk as far as the road north of Stoops Moss

and then turn left for 1km to Dent Head Viaduct. The other, for a medium length walk, is to continue as for the long walk past

Wold Fell to reach the Arten Gill track and then to turn left to Stonehouse Farm (2km) and south along the road to Dent Head

Viaduct (2km).

It is usually assumed that Whernside’s name derives

from the querns, or stone mills for grinding corn, that

were extracted from its slopes. However, Harry Speight,

in his 19th century guides, says that it comes from the

Anglo-Saxon word for ‘warn’, since anyone on the

ridge, which separated the Anglo-Saxons to the east

and the Norse to the west, could give warnings. At least

this draws attention to the differences east and west of

Whernside: the Anglo-Saxons were arable farmers and

lived in small villages; the Norse were sheep farmers

who preferred isolated farmsteads.

Deepdale Beck is a substantial tributary of the Dee

that drains the basin that lies north of the ridge separating

Deepdale from Kingsdale. Deepdale itself is a rarely

visited dale, quieter even than Dentdale and with, as

the name would suggest, a deeply incised valley. Its

hay meadows are a Special Area of Conservation under

European law. The road over to Kingsdale is not often

travelled but those who do tackle it are rewarded with a

roadside view of Lockin Garth Force.

Right: One of the Whernside Tarns

Right: One of the Whernside Tarns

The Craven Way, an ancient track linking Dent

and Ingleton, leads around Whernside, reaching a

height of 540m. The walk from the Craven Way past

the surprisingly large Whernside Tarns provides a good

ascent of Whernside. Combined with a drop down to the

Kingsdale road and then a walk through Deepdale, it

gives an excellent all-day expedition from Dent.

The River Dee begins to behave itself, flowing

steadily over an even bed, as it passes north of Dent,

the centre of Dentdale. The Domesday Book records

Dentone, which became Dent Town, and now plain Dent

– although it is far from plain: its narrow, cobbled streets

and whitewashed walls provide a distinctive, attractive

character.

The Church of St Andrews has Norman foundations

and was largely rebuilt in the 15th and 17th centuries. The

floor around the altar is paved with Dent marble, both

the black and grey versions. Next to the church is the

old grammar school (now a private home), built in 1604

from funding provided by Dentdale benefactors. The

school closed in 1897 but the governors still meet for

the enjoyable task of distributing money from the still-existing charities to local pupils.

Like all grammar schools, Dent’s existed to educate

young men in the delights of Latin and Greek grammar.

Young women were trained in more practical skills,

amongst which knitting was the most renowned in

Dentdale. Girls were sent, not always willingly, to Dent

from around the region to learn the art. The activity

peaked in the 18th century when socks and gloves were

supplied to the army. The narrow streets then appeared

narrower still because the houses had over-hanging

galleries where people sat to knit and chat.

On the streets today is the Sedgwick Memorial,

a huge Shap granite boulder, in honour of Adam

Sedgwick. The Dent Fault that runs through Dentdale

partly accounts for the differences between east and

west Dentdale. To the east, becks cut deep gills in the

V-shaped valley and the fields are large and walled; to

the west, the slopes are gentle with fields hedged and

with deciduous trees.

In 2006 the Flinter Gill Nature Trail and the Dent

Village Heritage Centre were opened, the latter helping

immensely to clear the attics of local farmsteads. In fact,

the leaflet for the nature trail existed before the trail did,

showing it to be a fine piece of creative literature, with

waulking, deiseal, sniggin, Dancing Flags and a Wishing

Tree. Its wishful thinking is symptomatic of a problem

with the tourist industry, upon which Dent now depends:

it is liable to ruin the very things that appeal to tourists

in the first place.

Self-defeatingly, Dentdale sells itself as ‘the hidden

valley’. It can be entered by the railway and by five

narrow roads (from Rawtheydale, Garsdale, Ribblesdale,

Kingsdale and Barbondale), all of which feel like back

entrances. It should be a green, restful haven but the

more we are persuaded to visit it the less hidden it will

become. In the summer the cobbled streets are already

thronging with people and cars. There seems little need

for artificial trails or for the air of desperation that

pervades Dent’s publicity.

Flinter Gill provides a pleasant stroll along a stony

track by small waterfalls but if the crowds are encouraged

there it will soon need litter bins, barriers (to stop people

slipping on the dangerous ‘dancing flags’), and so on.

The 1km trail ends at a “magnificent viewpoint” where

a toposcope tells us what we can see, leaving the fells

above still empty for those with a bit more energy.

Above this point, Flinter Gill runs from the northern

slopes of Great Coum (687m), an underrated hill that

displays its great coum or cirque towards Dentdale. All

three north-facing slopes of Dentdale have their cirques,

gouged out in the Ice Age (Middleton Fell has Combe

Top and Combe Scar; Whernside has Combe and Combe

Bottom) but Great Coum is the most impressive. The

southern ridge of the cirque, past the old quarry where

Dent marble was also mined, is the best ascent. The view

is excellent, from Whernside nearby to the Howgills and

the Lake District in the distance and to the south the

lower Lune valley.

Left: The Megger Stones

Left: The Megger Stones

Right: Whernside from the Occupation Road

Below Great Coum, on a rise overlooking Dentdale,

stand the Megger Stones, a group of ten or so cairns

showing varying degrees of competence at cairn-building.

The Megger Stones are just above the Occupation Road

or Green Lane, as the OS map calls it. It is named from

when the fells, used for common grazing, were enclosed

or occupied in the 1850s. It may be assumed to be an

ancient track, like the Craven Way, but it is not marked

on an OS map of 1853. It reaches a height of 520m

around the head of Deepdale and, although rutted and

muddy, provides a fine high-level walk.

From the Occupation Road we have a good view of

Rise Hill, which some call Aye Gill Pike, although there

is nothing pikey about it. It rises gently and uniformly

north of Dentdale like an enormous backcloth, to reach

556m. Although the ridge now has stiles over the many

walls it is no great pleasure to walk its boggy length. If

you must conquer it, a frontal assault is possible from

a permissive path that runs north through Shoolbred

(northeast of Church Bridge). At the eastern end of the

ridge, the OS map indicates “Will’s Hill or Peggy’s Hill”.

Did Will and Peggy really argue over the ownership of

this dismal hill, which is actually more of a morass?

The Dee flows west to Barth Bridge, below the small

village of Gawthrop, and by the Helmside Craft Centre

to the north and Combe Scar to the south, and on to Rash

Bridge. Here, we pause to point out a general problem

concerning the maintenance of bridges. Bats like to

roost in crevices under bridges and they are protected

by law, it being illegal to damage or destroy bat roosts.

Fifteen roosts were found under Rash Bridge in 1994, so

delaying repair work. The bats subsequently returned,

although they did not after similar repair to Barth Bridge

upstream.

[Update: I think that the Helmside Craft Centre has closed

and the building is now a B&B.]

By Rash Bridge is an old woollen spinning mill.

There was an even older corn mill here, as there are

records of one being demolished in 1590 after a dispute

over whose land it was on. Before food was readily

transported, cereals were grown locally, as oats were

part of the staple diet. The ownership of corn mills was,

therefore, an important matter. The Normans required all

grain to be ground at the lord of the manor’s mill and

not within individual households, which obviously gave

power to the lord and his manor. The custom gradually

lapsed and the corn mills that survived into the 18th and

19th century were often converted for textiles and other

uses.

After a further 2km, the Dee joins the Rawthey, by

the narrow Abbot Holme Bridge.

Dentdale from Combe Scar, with Great Knoutberry Hill in the distance

Walk 12: Middle Dentdale

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Dent (704872).

The character of Dentdale is best appreciated in the valley, so this walk is on the lower slopes, with an optional extension to

a medium height, to provide good views of the dale.

Walk through Dent, keeping left past the church, to Church Bridge and then turn left to follow the Dales Way west for 2km

to Barth Bridge. At Barth Bridge take the footpath north to High Barth and then follow this path that winds its way east through

a series of farmsteads (including High Hall, Scotchergill and Peggleswright) to Bankland. You will become well practised at the

art of locating and passing the various stiles.

Now walk east for a little over a kilometre on the quiet road past Gibbs Hall to Ibbeth Peril waterfall. Cross the footbridge

(behind the lay-by just east of the waterfall) and then take the equally quiet road west for 1km to Rise View, where you drop down

to the footbridge over the Dee and then continue on the north bank to Tommy Bridge.

Cross the bridge and continue southwest to Bridge End, at which point you have a choice. If the pubs beckon, continue along

the Dales Way to Church Bridge and Dent.

Otherwise, cross Mill Bridge over Deepdale Beck and immediately take the footpath (signposted “Deepdale Road 1/4m”)

south to Scow (about 1km). Turn right to Peacock Hill and then take the wide path of Nun House Outrake that leads up to Green

Lane, which gives good views of Dentdale and of Rise Hill opposite. Take this track west and after 2km turn down by Flinter

Gill, to return to Dent.

Short walk variation: Walk to Church Bridge and turn east along the Dales Way. Walk for 2km to Bridge End. From there, pick

up the last part of the long walk, that is, south to Scow, along Nun House Outrake, Green Lane and Flinter Gill to Dent.

The Rawthey from the Dee

Right: Brigflatts

Beyond a bridge for the old Lowgill-Clapham railway

line, the Rawthey passes near Brigflatts, a building

invariably described as the oldest Quaker meetinghouse

in northern England (a rather odd claim as ordinary

farmhouses were used as meetinghouses). Brigflatts was

built in 1675, when Quakers were still being persecuted

and meeting surreptitiously. Whether Brigflatts was

overtly declared to be a Quaker meetinghouse in 1675,

I don’t know, but as George Fox stayed there in 1677

its function could hardly have been a secret. Today its

peaceful sturdiness seems to embody some of the tenets

of Quakerism although the earlier Brigflatts probably

did so better, as until 1881 there was a soil floor across

which water from the nearby pond flowed.

Brigflatts inspired the greatest work of the

Newcastle-born, modernist poet Basil Bunting (1900-1985), who described himself as having been “brought

up entirely in a Quaker atmosphere” but who was not a

Quaker himself. The poem Briggflatts, written in 1966,

is described by the Oxford Companion to English

Literature as “long, semi-autobiographical and deeply

Northumbrian” (although Brigflatts was never in

Northumbria).

After passing another Hebblethwaites and the

Holme Open Farm, the Rawthey is joined by Haverah

Beck, which runs past Ingmire Hall in the narrow finger

of land between the Rawthey and the Lune. Ingmire Hall

was the seat of the Otway family from the 16th century

or earlier. Sir John Otway was an eminent lawyer during

the Civil War (1642-51) and, as a Roman Catholic, was

sympathetic to the problems of the Quakers and provided

them with valuable legal advice. The hall passed through

the female side to the Upton family of Cornwall. After

acquiring two hyphens, a descendant, Mrs Florence

Upton-Cottrell-Dormer, became a benefactress to

Sedbergh, donating Queen’s Gardens and the cemetery.

Beyond Middleton Bridge, the Rawthey, at last,

reaches the Lune.

Two views from the same spot by the Rawthey, as it approaches the Lune:

Above: North to the Howgills. Below: South to Middleton Fell.

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Upper Rawtheydale)

The Next Chapter (Middleton Fell)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: Stone Hall, near Sedbergh

Right: Stone Hall, near Sedbergh

Left: Welcome to Sedbergh

Left: Welcome to Sedbergh

Right: Artengill Viaduct

Right: Artengill Viaduct

Right: Ibbeth Peril

Right: Ibbeth Peril

Right: One of the Whernside Tarns

Right: One of the Whernside Tarns

Left: The Megger Stones

Left: The Megger Stones