The Land of the Lune

Chapter 7: Middle Lunesdale and Leck Fell

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Middleton Fell)

The Next Chapter (The Greta Headwaters)

View towards Kirkby Lonsdale from Brownthwaite

The Lune from Barbon Beck ...

Left: Underley Bridge

Left: Underley Bridge

A kilometre from the Barbon Beck junction the

Lune passes a badly eroded west bank, just before

Underley Bridge. The inordinate ornateness of

this bridge reflects its limited functionality, for it was

built in 1872 (or 1875, depending which datestone on

the bridge you believe) to enable gentry and their lady

folk to travel in their coaches from the Underley estate to

the Barbon railway station. The bridge was built for Lord

Kenlis, later the Earl of Bective, MP for Westmorland,

whose father, Lord Bective married Amelia, the daughter

of William Thompson, of the wealthy Westmorland

Thompson family, who was a Lord Mayor of London

and previous owner of the Underley estate. The bridge

is adorned with battlements, gargoyles and a motto

– consequitur quodcunque petit, that is, one attains

whatever one seeks (Barbon railway station, I assume).

Before the Lune sweeps south under a dramatic cliff

a small beck enters on the left. This has run off Barbon

Low Fell through Grove Gill and past Whelprigg, another

of Loyne’s fine country houses. The Whelprigg estate

belonged to the Gibson family, for whom Whelprigg was

built in 1834, in an imposing Victorian style. In the fields

by the drive to the house is an ancient cross, on the line

of the Roman road, and to the north six trees that seem

uniquely honoured by having their types specified on

the OS map (four ash and two oak), presumably because

they mark the parish boundary.

To the south of Whelprigg runs the old track of

Fellfoot Road, where it is difficult to turn a blind eye to

the Goldsworthy Sheepfolds (as we have done so far):

there are sixteen of them, all created in 2003.

Right: Underley Hall

Right: Underley Hall

The Lune next runs by the elegant mansion of

Underley Hall. This was rebuilt in 1826 in the Gothic

style and later embellished and enlarged by the Earl

of Bective. The Earl and his successor at Underley,

Lord Cavendish-Bentinck (MP for South Nottingham),

who had married the Earl’s daughter, Olivia, and, of

course, the Countess and Lady, lived in the style that

befits such names. At one time, the estate employed 163

people, including 26 gardeners. The hall was known

for its shooting parties, a regular visitor to which was

the young Harold Macmillan, future Prime Minister. In

the Annals of Kirkby Lonsdale (1930), Lord Cavendish-Bentinck was described as “a magnificent specimen

of an English country gentleman”. Perhaps the author,

Alexander Pearson, was one of the 163 - at all events,

he is unlikely to have been neutral to the influence of the

Underley owners in the Kirkby Lonsdale region. On Lady

Cavendish-Bentinck’s death in 1939, the estate passed

to a cousin, Madeleine Pease. Since 1976 Underley

Hall has been a residential school for up to sixty young

people with emotional and behavioural difficulties but

the estate is still owned by the Pease family.

To the east is the old village of Casterton. It may not

be as old as its name suggests since there is no evidence

of a Roman castle on the site but it is old enough to

have been included in the Domesday Book. It is a small

village of class, with scarcely a house lacking style. It

has all the essentials of life: a school, a church, a garage-cum-shop, a pub and a golf course.

The Goldsworthy Sheepfolds were created between 1996

and 2003 by the environmental sculptor Andy Goldsworthy

during a project funded by Cumbria County Council. The

46 folds were built from existing folds that were derelict

or built anew where they were indicated on old maps.

Goldsworthy uses natural materials to create his art forms

and “feels the energy from nature and transcends that energy

into art form”. Each sheepfold was thus reinvigorated by

this new energy and re-connected to the farming traditions

of Cumbria. Inspiration, however, seems rather thin along

Fellfoot Road: all sixteen folds are similar, with a large

boulder enclosed in a small fold.

It is more in the spirit of the project if the sculptures

are appreciated by encountering them serendipitously and

by being momentarily confused by the strangely modern,

possibly functional, structures. (On our journey so far we

have passed Goldsworthy Sheepfolds at Raisbeck (the pinfold shown in Chapter 1),

Scout Green, Bretherdale, Cautley Crag, and

Barbondale.) However, now that the project is complete

and the folds are listed in leaflets and on websites,

inevitably people will set out purposefully to tick them off.

Whether they warrant such explicit attention I leave art-connoisseurs to judge.

Right: Toll Bar Cottage, Casterton

Right: Toll Bar Cottage, Casterton

Casterton School is an independent

boarding and day school for 320 girls (with

20 lucky? boys as day pupils). The school

began in the 1830s when Low Wood School,

which the Rev. William Carus Wilson had

established at Tunstall to train girls to be

servants, and the Clergy Daughters’ School

(of which, more shortly) that he’d started

at Cowan Bridge were both transferred to

Casterton. To help the clergy daughters

feel more at home, he had the Holy Trinity

Church built. And to help himself feel at

home, he moved into the neo-classical

Casterton Hall, which had been built in

1812 for his father.

Below Casterton Hall stands the 17th

century Kirfit Hall, with what looks like

a peel tower but is apparently a staircase

tower. Because of a planning dispute, one

of its barns has been garishly painted, in order to enliven

Ruskin’s View, which is a viewpoint at the top of a steep

bank of the Lune 1km south.

Left: St Mary’s Church, Kirkby Lonsdale

Left: St Mary’s Church, Kirkby Lonsdale

Near Ruskin’s View is Cockpit Hill, a 40m diameter,

overgrown mound that is thought to be the site of an

old motte and bailey castle, and behind it is Kirkby

Lonsdale’s Church of St Mary the Virgin, a substantial

edifice with many notable features. For most old

settlements, the church is the largest and most important

structure and it therefore becomes a focus for passing

visitors, even for those who rarely venture into churches.

Here, there is much of non-specialist

interest, both outside and inside the church.

Outside, the visitor may contemplate the

self-closing mechanism of the churchyard

gates, the oddly placed clocks on the tower,

the intriguing gazebo painted by Turner in

1818, and the pillar in memory of five young

women burned to death in 1820. Inside the

church, there’s some fine Jacobean wood

carving and on the northern side of the

nave there are three large Norman arches,

two of which have distinctive diamond

patterns. Some doorways and part of the

tower are also Norman. The church is

therefore at least as old as the 12th century

and is probably of Saxon origin, although

there has been much rebuilding, notably

in the 18th century and again in 1866.

Ruskin commented in 1875 that the church “has been

duly patched, botched, plastered and primmed up; and

is kept as tidy as a new pin”, in contrast to the bank of

what we now call Ruskin’s View, which was a “waste of

filth, town drainage, broken saucepans, tannin and mill-refuse”.

Passing through the churchyard, we enter Kirkby

Lonsdale, the most desirable location in Loyne, or so

estate agents tell us. It lies by the A65, midway between

the Lakes and the Dales, and does not try too hard to

detain tourists travelling between the two. The narrow

main street has shops and restaurants of refinement, even

trendiness (as epitomised by the renaming of the Green

Dragon as the Snooty Fox), and there is a profusion

of hanging baskets and other floral decorations. The

market square, however, has an unstylish crown-shaped

structure, now serving as a bus shelter, which used to

have a sort of dome with a cross atop. It was donated in

1905 by the vicar of Kirkby Lonsdale, whose generosity

could presumably not be declined.

The ambience is suburban, rather than rural, for,

apart from Ruskin’s View, Kirkby Lonsdale is inward-looking, focused on its own business, with little outlook

onto the surrounding fields. The older buildings are

of limestone, which outcrops locally. Apart from the

church and pubs, there are few buildings earlier than

the 18th century and on the outskirts many standard 20th

century houses.

Ruskin’s View is the only point along the Lune that the

Ordnance Survey considers worthy of a viewpoint symbol.

I’d prefer that OS maps kept to matters of fact rather than

opinion. For what it’s worth, my opinion is that the view is

OK, but neither high enough to provide an extensive view

of the Lune valley, with its fine surrounding hills receding

into the distance, nor low enough to enable an appreciation

of the sights and sounds of the riverside. Instead, we see one

bland bend of the Lune, with a backdrop of Brownthwaite

and Middleton Fell, among the least impressive of Loyne’s

hills.

The viewpoint is called Ruskin’s View, in thanks to

the art critic and thinker John Ruskin, whose opinion was

that “Here are moorland, sweet river and English forest at

their best … [the view is] one of the loveliest in England

and therefore in the world”. According to the Cumbrian

Directory, Ruskin said this in the 1870s after seeing

J.M.W. Turner’s 1818 painting of the view. One might

query Ruskin’s status as an art critic if he really considered

this view comparable to the one from his own window at

Brantwood, looking over Coniston Water.

Ruskin was a fervent promoter and protector of

Turner’s reputation. So much so that art historians

had always believed his statement in 1858 that he had

destroyed a set of erotic paintings by Turner, not wanting

his reputation to be sullied. However, the paintings were

found in 2005. Ruskin himself was fond of young girls. So

that’s two reputations sullied.

My point is that we should not just follow the opinions

of others – eminent aesthetes such as Turner or Ruskin,

or the OS, or, certainly, me. It is better to form your own

judgements about this and other views of the Lune.

Left: The other view from Ruskin’s View, looking to The Island

Left: The other view from Ruskin’s View, looking to The Island

Although there are few features of antiquity,

Kirkby Lonsdale is old, appearing in the Domesday

Book as Cherkeby Lownesdale and being granted its

market charter in 1227. The manor of Kirkby Lonsdale,

including the church, was given to St Mary’s Abbey

in York in the 1090s and after the Dissolution of the

Monasteries the church rights were granted to Trinity

College, Cambridge. Kirkby Lonsdale used to play

up to its history, without going back quite that far, by

holding a Victorian Fair in September, with participants

in period dress. This tradition was ended in 2008, being

considered to have outlived its usefulness.

Up to the 19th century there was a series of mills by

what is now called Mill Brow. From the market square

Jingling Lane drops down towards the Lune. The lane

meets up with the footpath that proceeds from

below Ruskin’s View alongside the Lune, where

there was a millrace for further mills. Anyone

walking along this path will notice the flood debris

in the tree branches above their head, indicating the

torrents that sometimes rage through this narrow

valley. All the more surprising, then, that the

elegant, three-arched Devil’s Bridge has withstood

the Lune for five centuries, or even longer. The date

of the bridge is unknown but, to be on the safe side,

it is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Some think

it to be Roman, but this seems unlikely; others can

detect the same Norman hands as built the church;

others refer to records of repairs in 1275 and 1365

(which show only that there was a bridge here but not

necessarily this one); others consider the form of the

arches to be late 15th century at the earliest.

The name of the bridge is more recent, for until

the 19th century it was simply the Kirkby Lonsdale

Bridge. The uncertainty about the origin of the bridge’s

remarkable design encourages thoughts of a supernatural

agency. The legend is, in brief, that a woman entered a

Faustian deal with the devil to get the bridge built and

then sacrificed her dog to meet the conditions of the

deal.

For many people, hurrying between the Lakes and

the Dales and pausing at the Devil’s Bridge, this is the

only glimpse they will have of the Lune. It is a pity

that quiet contemplation of the bridge and the scenery

is difficult. There are normally crowds milling around

the snack bars and over the bridge and, at weekends,

motorcyclists, canoeists, picnickers, and maybe even

divers off the bridge. If we could but focus upon it

we’d appreciate the unique beauty and elegance of

the old bridge, 12m high, with ribbed, almost semi-circular arches, two of 17m and one of 9m span. The

breakwaters continue to the parapet to provide refuges

in the roadway, which with a width of only 3.5m is too

narrow for modern vehicular traffic. Below, the Lune

swirls through sloping crags.

The Lune runs under the A65 at Stanley Bridge,

built in 1932 150m south of the Devil’s Bridge. Stanley

– that is, Oliver Stanley, MP for Westmorland, after

whom the bridge was named – does not compete with

the devil. Instead, the new bridge, with its off-yellow

colouring and bold single span, provides a strong, if

inelegant, contrast. Just south of Stanley Bridge the

Lune enters the county of Lancashire.

Devil's Bridge and Stanley Bridge

The Top 10 bridges in Loyne

1. Devil’s Bridge, Kirkby Lonsdale

2. Batty Moss (Ribblehead) Viaduct

3. Loyn Bridge, Hornby

4. Lowgill Viaduct

5. Lune Aqueduct, Lancaster Canal

6. Skerton Bridge, Lancaster

7. Crook of Lune Bridge, Lowgill

8. Artengill Viaduct, Dentdale

9. Lune’s Bridge, Tebay

10. Waterside Viaduct

Below Kirkby Lonsdale the Lune is accompanied

by the Lune Valley Ramble, which continues, mainly

on its west bank, for 26km to Lancaster. Since the more

varied and major part of the Lune valley lies to the north

of Kirkby Lonsdale it should perhaps be called the

Lower Lune Valley Ramble. This may seem pedantic

but the Lune is often underrated because the remit of the

body most concerned with its support and promotion,

Lancaster City Council, seems to end at the county

border. Its 2009 brochure describes the Lune valley as

“a pocket-sized part of England” that runs for “15-20

miles between Lancaster and Kirkby Lonsdale”. Its

‘official Lune Valley visitor website’ similarly considers

the Lune valley to begin at Kirkby Lonsdale. So I’ve

managed to write half a book about a river that

has not existed until this point.

The Ramble is a fine walk, the part here being best

tackled on a bright morning with the sun sparkling on

the rippling surface, with distant views of Leck Fell,

Ingleborough and the Bowland Fells. South of the

bridges oystercatchers assemble in March on their way

to their nesting sites on the shingle of the Lune. These

birds of the lower Lune, easily recognised by their long,

straight, dark red bill, red legs, and black and white

colouring, are more often seen in small numbers, flying

fast, with a shrill call.

One kilometre from Kirkby Lonsdale the Lune

passes under the 130km Haweswater Aqueduct, which

transports up to 500 million litres of water every day

to Manchester. It was completed in 1955, 36 years after

permission for the controversial Haweswater Reservoir

had been granted.

Showing excessive concern for walkers’ safety,

there are warnings to keep on the landward side of a

small embankment for flood protection. I assume the

real intention is to keep us away from fishermen, but if

they are absent the river-edge is much the better place

to be.

The next significant tributary is Leck Beck, joining

from the east.

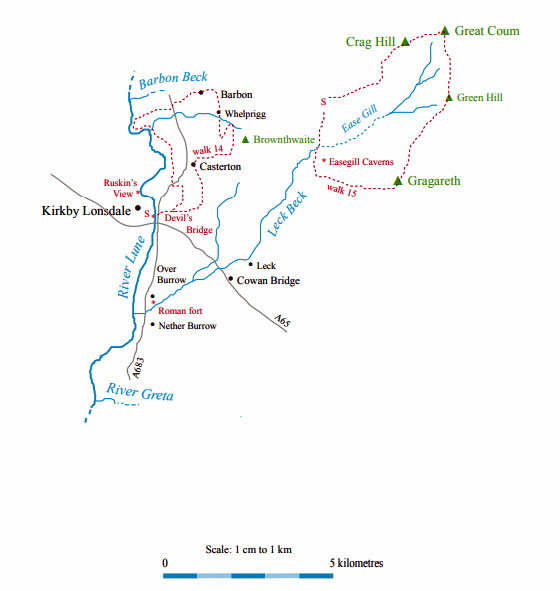

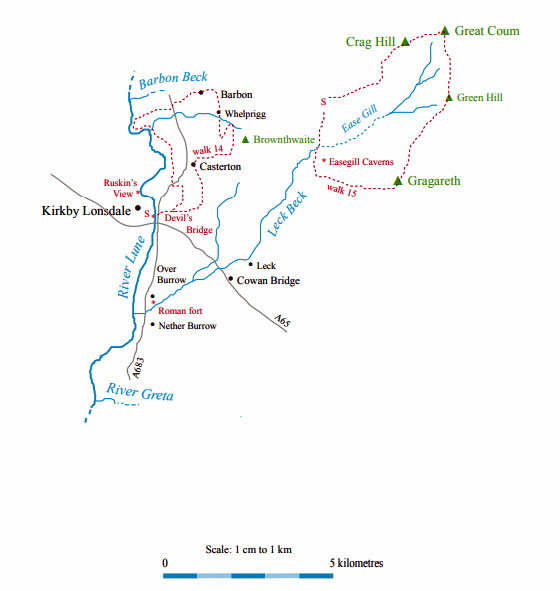

Walk 14: A Loop between Kirkby Lonsdale and Barbon

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Near the Devil’s Bridge (617783).

This is a walk along country lanes and tracks, passing a variety of rural houses and reaching no great height. There is the

chance to refuel in Barbon.

Head east, past the caravan park, towards Chapel House and then follow Chapelhouse Lane to High Casterton, passing the

golf course on your left. After the Old Manor, cross the junction, following the sign to Low Casterton. Turn right at the Holy

Trinity church towards Langthwaite.

Immediately after Langthwaite take the footpath south to Fellfoot Road, which you follow north, past some Goldsworthy

Sheepfolds, until it drops down to a road. Turn left at the road and walk to Fell Garth. Take the path north past Whelprigg to

Underfell, to drop into Barbon by the church. From Barbon, walk southwest along Scaleber Lane to Low Beckfoot. You could

take a short detour north to see the packhorse bridge at Beckfoot Farm. At Low Beckfoot take the path west to the Lune.

At the Lune turn south to follow the long bend past Underley Bridge and then swing back to join Lowfields Lane. Walk

east and take the path south, below Underley Grange, to the wood below Gildard Hill, with views on the way across the river

to Underley Hall. If you should, accidentally, of course, stray west from the path in the wood, you would have a view down the

steepest and highest Luneside bank.

The path continues south to Casterton Hall and then across the field to the A683, where it is best to turn left for 100m or so

(take care) and follow the track (Laitha Lane) south from Toll Bar Cottage. This returns you to the Devil’s Bridge if you turn right

at the end (or via a short cut through the caravan park on the right).

Short walk variation: For a short walk it is necessary to forego Barbon. Follow the long walk as far as the junction after the Old

Manor and then turn right for 1km, over the old railway line and past Fell Yeat, the home of Brownthwaite Hardy Plants, which

deals with speciality perennials. Turn left at Fellfoot Road and walk north for 1km past some Goldsworthy Sheepfolds. Then turn

west past Langthwaite and on to Casterton. Cross the A683 and walk through the school to pick up the footpath that goes south

past Casterton Hall. Follow the last part of the long walk back to the Devil’s Bridge.

Leck Beck

The mature beck that gushes from the fellside at Leck

Beck Head emerges after an eventful and secretive

infancy. The waters that drain the southern slopes below

the fine ridge that arches from Crag Hill to Great Coum

and Gragareth form the becks of Aygill and Ease Gill,

which proceed normally enough over the high moorland

until they reach beds of limestone at about the 350m

contour, at which point they begin to disappear through

various potholes and caves.

The ridge to Gragareth from Great Coum

We have flirted with potholes and caves in Dentdale

and Barbondale but a confession is now required. My

guiding principle has been to write only about what I

have seen, wherever possible, and this has led me to visit

every one of Loyne’s 1285 sq km – but I draw the line

at going under them as well. This is unfortunate because

potholes are one of the few things in Loyne for which

we can dust off our superlatives, as it is undoubtedly

England’s best potholing region. However, I cannot

imagine ever standing at the entrance to a pothole and

opting to spend the next few hours in the damp, dark,

dangerous depths when I could be striding the hills, with

fresh air in my lungs, the wind in my hair, a spring in

my step, and a view in all directions. I can appreciate the

physical, mental and scientific challenge of potholing

but I prefer to resist it.

Therefore, apart from modest forays into cave

entrances and the tourist trips into White Scar Caves,

Ingleborough Cave and Gaping Gill, all the potholes

and caves are unknown territory to me. The little that I

say about them is passed on, second hand, in good faith.

Those who wish to venture seriously (and there should

be no other way) into potholes should consult more

reliable first-hand sources.

The potholes into which Ease Gill disappears are

part of the Easegill Caverns, which form, according to

Natural England’s description of the Leck Beck Head

Catchment Area Site of Special Scientific Interest, the

longest cave system in Britain and the 11th longest in the

world. Some call it, or used to call it, the Three Counties

System, as it stretches from Aygill (in Cumbria) across

Leck Fell (in Lancashire) to Ireby Fell (on the North

Yorkshire border). The caves under Casterton Fell (from

Lancaster Hole, Bull Pot of the Witches and others) have

60km of connected passages and these have a flooded

connection to a further 12km under Leck Fell (from Lost

John’s Cave and others). An additional 12km of passage

under southern Leck Fell are, as yet, unconnected. An

idea that there would be an eastern link to the Kingsdale

caves seems to be dormant. To the west the cave system

is ended by the Dent Fault.

Walk 15: Leck Fell, Gragareth and Great Coum

Map: OL2 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: The track near Bullpot Farm (663815).

This expedition provides a surface exploration of some potholes of the Easegill Caverns followed by a high-level ridge

walk.

From Bullpot Farm walk south 1km to cross a stile below Hellot Scales Barn. (In the very unlikely circumstance that Ease

Gill cannot be forded at this point, be sensible: abandon the suggested walk. Content yourself with a walk along the north bank

to view the rare sight of waterfalls in the Ease Gill valley and return to Bullpot Farm.)

Detour for 100m up the dry bed to view a chamber with a

U-shaped (dry!) waterfall (shown in the sixth of the eight photos below). Some people

call this Ease Gill Kirk but the name is properly applied to a less accessible but larger and more spectacular amphitheatre with

overhanging cliffs about 200m downstream from the stile. The Kirk (or Church, as it used to be called) is said to have been a

clandestine meeting place for Quakers. Returning to the stile, cross the bed of Ease Gill (leaving Cumbria for Lancashire) and

follow the footpath south. At a grassy slope a side-path allows a detour to see the real Ease Gill Kirk.

Leave the footpath before reaching a wall and head southeast across a field, viewing Big Meanie and Rumbling Hole en

route. Note the Three Men of Gragareth, the central group of a set of cairns, on the horizon as you cross the field. These are your

next objective. On reaching the road, take the track above Leck Fell House north for 100m and then scramble up to the Three

Men.

From the cairns, take a faint path east for 1km to the Gragareth trig point, and then continue for 150m to reach a wall (peer

over the wall into North Yorkshire). Walk north by the wall for 5km, passing Green Hill (628m, the highest point of Lancashire)

and the County Stone (the northernmost point of Lancashire) to reach Great Coum, from which there is an excellent view of the

Lakeland hills, the Howgills, the nearby Yorkshire Dales peaks, the lower Lune and Morecambe Bay.

[Update: In 2014 it was determined that Gragareth was 0.5 metres higher

than Green Hill and therefore the highest point of Lancashire.]

Walk west by the wall to Crag Hill (1km) and continue southwest to Richard Man, a rather inconspicuous set of stones (a

further 1km). At this point walk south for 250m to a parallel wall, which you then follow southwest for 2km to reach the Bullpot

Farm track.

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk as far as the track above Leck Fell House and then follow that track north for 2km.

Leave the track to follow the wall as it drops down to Ease Gill. Follow Ease Gill south for 1km until you reach a rather rickety

bridge. It is worth a short detour beyond the bridge to see Cow Dub. Return to cross the bridge and then follow the path northwest

for 1.5km back to Bullpot Farm.

It must be galling to the Yorkshire Dales National

Park, renowned for its potholing, to find that its borders

exclude Britain’s longest cave system. The old county

border that ran from Gragareth to Great Coum and into

Barbondale neatly steals the Easegill Caverns from the

Yorkshire Dales. Perhaps this will be remedied by the

review of the National Park boundaries.

The details of this three-dimensional underworld

are complex to unravel but the cause of the cave system

is as we have seen before. Water runs off the shale and

sandstone upper slopes to sink at the limestone boundary,

to make its way underground to the impermeable lower

layer and eventually re-emerge, in this case at Leck

Beck Head. Normally the bed of Ease Gill is dry for 2km

above Leck Beck Head but in flood conditions the caves

fill and Ease Gill becomes a torrent. Leck Beck actually

emerges about 100m north of the present line of the bed

of Ease Gill.

On the surface there is the barest indication of the

wonders underneath. At Lancaster Hole, for example,

there is only a manhole cover to see, unless it happens

to be raised, in which case you can peer down the 35m

shaft. The discovery of Lancaster Hole in 1946, which

really began the exploration of the Easegill Caverns, has

entered potholing legend: a resting caver noticed the

grass moving more than the breeze warranted, inferred

that a draught was issuing from underground, and shifted

a few rocks to reveal the pothole.

The Lakes and Dales National Park boundaries are to be

reviewed by Natural England (the review was postponed

until a decision on a South Downs proposal was reached,

which it finally was in April 2009). It seems likely to

propose that the Dales be extended westward to include

the northern part of the Howgills, Middleton Fell, Leck

Fell and Wild Boar Fell and that the Lakes be extended

eastward to include Birkbeck Fells – in short, that the upper

Lune becomes a border between the two National Parks.

There are many factors involved in determining

National Parks, as they are legal entities with administrative

roles. One factor concerns their role in conservation. It is

assumed that ‘undesirable’ developments would not be

permitted within a National Park. Therefore, by extending

the boundaries, the area protected from such developments

would, it is hoped, be increased.

In a rational world boundaries would not be determined

by politics or history but by natural properties that give a

region its coherence. In our case, the Dent Fault suggests

that Wild Boar Fell and Leck Fell (but not the Howgills

and Middleton Fell) belong to the Dales. The characteristic

areas of the Lake District are on igneous rocks that differ

from Loyne’s sedimentary rocks, including the Shap Fells,

which are now within the Lake District National Park (but

if we follow this line of reasoning we might conclude that

the areas south of Windermere and Coniston don’t belong

in the National Park either!).

Geologically, the Shap Fells, Birkbeck Fells, the

Howgills and Middleton Fell form a homogeneous

region. Perhaps this region could be designated an Area

of Outstanding Natural Beauty, for even the strongest

supporter could not claim it equal to the two National

Parks. It is, however, unlikely that areas already within the

National Parks (the Shap Fells and the southern Howgills)

will be excluded. Let’s leave it to the experts.

[Update: The National Park boundaries were duly revised in 2016.

As expected, the National Parks became bigger. The Lake District adopted the Birkbeck Fells,

Bretherdale and Borrowdale. The Yorkshire Dales border was moved north to include Wild Boar Fell, the

northern Howgills and the Orton Fells as far as Maulds Meaburn. The western boundary was moved

to include not only Barbondale and Middleton Fell but part of the Lune valley.

The River Lune can therefore now be considered a river of the Yorkshire Dales since it

is no longer on the border for a few miles but is actually within the National Park from its

source to Tebay and from Borrowdale to Kirkby Lonsdale.]

Ease Gill runs from the slopes of Great Coum ...

Ease Gill runs from the slopes of Great Coum ...

... and gradually disappears through limestone ...

... and gradually disappears through limestone ...

... the bed becoming completely dry in places ...

... the bed becoming completely dry in places ...

... though there’s usually a trickle at Cow Dub ...

... though there’s usually a trickle at Cow Dub ...

... below which the valley is dry and quiet ...

... below which the valley is dry and quiet ...

... with eerie grottos and waterless waterfalls ...

... with eerie grottos and waterless waterfalls ...

... meanwhile the underground waters of

Ease Gill are exploring the Easegill Caverns, as

many potholers also do by, for example, entering

Lancaster Hole ...

... meanwhile the underground waters of

Ease Gill are exploring the Easegill Caverns, as

many potholers also do by, for example, entering

Lancaster Hole ...

... and eventually, as the waters reach the

impermeable rock below the layer of limestone,

they re-emerge at Leck Beck Head near Ease Gill

Kirk to form Leck Beck.

... and eventually, as the waters reach the

impermeable rock below the layer of limestone,

they re-emerge at Leck Beck Head near Ease Gill

Kirk to form Leck Beck.

As Leck Beck runs through Springs Wood, a natural

wood unlike the many conifer plantations in the area, it

passes below Castle Hill to the east. Here are the remains

of – well, what exactly? There appears to be a roughly

circular ditch, 100m in diameter, with gaps to the north

and south. Within the ditch, there is some unevenness

and a few piles of rocks but no real sign of any building

– certainly no castle. It probably enclosed a few Iron Age

settlements. One thing we can be sure of: whoever lived

here had an excellent view of the lower Lune valley.

Left: The Leck Beck valley

Left: The Leck Beck valley

Across Leck Beck at High Park are the remains of

ancient settlements, visible on the ground as earthworks

and jumbled lines of rocks. Archaeologists tell us that

they date from 300 AD or so. Even older is the Casterton

stone circle, which lies southwest of Brownthwaite

Pike and dates from the late Neolithic or early Bronze

Age (2000-600 BC). There are about eighteen stones,

none higher than 30cm and some sunk in the grass,

in a 20m-diameter circle. It is said that 1,800 finds,

including drinking vessels, flint arrowheads and a

bronze spearhead, have been made here. The circle is

not, however, an impressive sight. In the same field are

many large piles of rocks, the remains of thick walls,

which are rather more intriguing.

You cannot see Kirkby Lonsdale from the stone

circle, as you might have expected since the stone circle

is marked on the display at Ruskin’s View. However,

if you climb to the prominent cairn on Brownthwaite

Pike, you are rewarded with an excellent view of Kirkby

Lonsdale, with Morecambe Bay behind, the Lakes

skyline to the right and the middle reaches of the Lune

to the left.

Leck Beck runs by the village of Leck, which is

not the traditional cluster of stone cottages: it is not a

cluster at all. The ingredients – an old mill, parsonage,

church, and school – are there but they do not seem to be

integrated to make a community. An ignored triangular

field looks like it would make a fine village green –

perhaps it once was, for many houses here were burnt

down in the 1800s after a smallpox outbreak. Leck Hall,

which was rebuilt in the early 19th century and bought

by the Kay-Shuttleworth family in 1952, stands apart.

From this outpost Lord Charles Shuttleworth serves

as Lord Lieutenant of Lancashire, a post instituted by

Henry VIII to deal with local defence. Perhaps the need

to repel Yorkshire invaders explains all the noise of

shooting heard hereabouts. Today, the Lord Lieutenant’s

role is to represent the Queen at events in the county and

to prepare programmes for royal visits to Lancashire.

At Cowan Bridge, Leck Beck passes under an

overgrown five-arched bridge for the old Lowgill-Clapham railway line. Cowan Bridge itself is bisected

by the busy A65. This is an ancient road along which

tolls were collected as early as the 16th century but

the traffic associated with the Yorkshire and Cumbria

woollen trade had died down by 1824, when the Brontë

sisters came. Cowan Bridge is now most remarked upon

because of its Brontë connection, excessively so, given

that it is the grim pestilence of the place that is recalled.

The Brontë connection began when the Rev. Patrick

Brontë sent four of his five daughters to the Clergy

Daughters’ School opened by the Rev. William Carus

Wilson in Cowan Bridge in 1824. They were only there

for a year, illness forcing them back to Haworth. Maria and

Elizabeth died of tuberculosis in 1825, although Charlotte

and Emily did, of course, survive to write novels. All they

wrote whilst at Cowan Bridge, however, was “Dearest

father, please, please get us out of this place”.

Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography (1857) of Charlotte

Brontë painted a harsh picture of the Clergy Daughters’

School (Lowood of Jane Eyre, perhaps derived from

the Low Wood School we met at Casterton) and of the

Rev. Carus Wilson (Mr. Brocklehurst), so much so that

threatened legal action brought changes to the third edition.

To put the Brontë’s illnesses into context, child mortality

in the region was so high at the time that average life

expectancy was only 26 years.

A plaque on the wall of Brontë Cottage by the old

road bridge commemorates the Brontë sisters’ brief and

unhappy time at the Cowan Bridge school.

South of Leck Beck, on Woodman Lane, there is a

poultry farm that is surprisingly large for such a quiet rural

area. Perhaps the authorities, too, were surprised, for the

buildings had neither planning permission nor an IPPC

(Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control) licence.

To avoid getting myself entangled in this legal dispute

I should clarify that ‘agricultural permitted development

tolerances’ allow a small amount of construction every

two years without planning permission. Lancaster City

Council refused a retrospective application in 2005, a

decision for which the council was later fined £87,000

as it was deemed unreasonable. Presumably this ensures

the future of Mayfield Chicks, if not the chicks.

Leck Beck next passes under Burrow Bridge,

whose two arches seem almost too low for the beck

when it is in flood. In alcoves on the bridge there are

acknowledgements to the work of those who built the

bridge in 1733 – labourers (on the west) separated from

management (on the east).

The bridge is midway between Nether Burrow and

Over Burrow, which together yield the novel parish name

of Burrow-with-Burrow. At the former is the 18th century

coaching inn, the Highwayman Inn, which has recently

been refurbished and resurrected as a ‘Ribble Valley

Inn’, a geographically remarkable transmogrification.

The Top 10 pubs in Loyne

(This ‘top 10’ has provoked more comment than all the

others combined. I think that I had better play safe and list

the pubs (generously, more than ten) in alphabetical order.

I am open to persuasion, financial or gustatory, from any

owner who feels their pub has been neglected.)

1=. Barbon Inn, Barbon

1=. Cross Keys Inn, Tebay

1=. Fenwick Arms, Claughton

1=. Game Cock, Austwick

1=. Golden Ball, Lancaster

1=. Hill Inn, Chapel-le-Dale

1=. Lunesdale Arms, Tunstall

1=. Marton Arms, Thornton-in-Lonsdale

1=. Redwell Inn, Gressingham/Arkholme

1=. Ship Inn, Caton

1=. Stork, Conder Green

1=. Sun Inn, Dent

1=. The Head, Middleton

1=. The Sun, Lancaster

1=. Water Witch, Lancaster

P.S. The Highwayman Inn is disqualified for calling itself

a Ribble Valley Inn.

[Update: I regret giving this list. I didn't visit pubs

often enough - and even less recently - to be qualified to provide such a list.

In any case, the quality of a pub changes as its ownership does, regularly.

The Highwayman Inn is, for example, no longer a Ribble Valley Inn, I think.]

If you walk to the gate at the drive of Burrow Hall

in Over Burrow and then 20m to the barn to the north

and look at the wall near the north end, about head high,

you will see a red sandstone block with carvings on it.

This is a remnant of Roman stonework and is all that can

be seen of the Roman fort that existed at Over Burrow

from the 1st to the 4th century.

Right: Roman stonework in Over Burrow barn

Right: Roman stonework in Over Burrow barn

The rest you must imagine. The gate to the hall

driveway is probably at the east entrance to the fort,

midway along the east wall. Burrow Hall itself, visible

up the drive, 140m away, is on the west wall of the fort.

The fort was roughly square, so the south wall was 70m

south of the drive, across the green field. The north wall

was similarly 70m north, where there are buildings now.

The fort thus enclosed about 2ha, enough space for a

thousand soldiers.

How do we know this, when there is so little to

see? The Roman’s Antonine Itinerary listed a fort

called Calacum 27 Roman miles from Bremetenacum

(Ribchester) and 30 Roman miles from Galava

(Ambleside) – in other words, here. In the past, Burrow

was regarded as a very old place and, not so long ago,

there was more evidence than there is today: William

Camden, in his great work Britannia (1610), the first

historical survey of Great Britain, wrote “… by divers

and sundry monuments exceeding ancient, by engraven

stones, pavements of square checker worke, peeces of

Roman coine, and by this new name Burrow, which with

us signifieth a Burgh, that place should seeme to bee of

great antiquity.”

Various excavations have been carried out,

particularly in the 1950s, to confirm the lines of the

walls and positions of the gates. About thirty coins have

been found, from Vespasian (69-79 AD) to Constantius I

(305-306 AD), but none from the 3rd century. Of course,

much remains unknown and may always be so. It is

assumed that a road went west across the Lune to Galava

although its route has not been traced. The road from

Low Borrowbridge, which we have been tracking south,

runs 1km to the east of the fort.

Burrow Hall is a substantial Grade I listed Georgian

mansion, best seen from the footpath to the north. After

the Civil War the Burrow estate was given to a Colonel

Briggs, who built the first hall in the 1650s. The estate was

sold to the Fenwick family in 1690 and Robert Fenwick,

Attorney General and MP for Lancaster, rebuilt the hall,

as we see it now, in 1740. After passing through various

hands, the estate was offered for sale in 2005 for £3.5m

and so, for what it’s worth, we have the estate agent’s

description of the interior of the building: the Baroque

ceilings, the marble fireplaces, the delicate cornicing of

its five grand reception rooms, the sumptuous master

suite, the stunning atrium with fabulous views, and so

on. The Burrow estate also includes 0.5km of fishing on

the Lune, which Leck Beck joins 300m below Burrow

Bridge.

The Lune from Leck Beck ...

The map shows a ford across the Lune immediately

after Leck Beck has entered the Lune and I can

vouch for the fact that it is indeed fordable, on foot

(sometimes). If the paddling expedition is from the east

and is timed properly, it is possible to sneak in on the

Whittington point to point steeplechases that are held on

Easter Saturdays in the fields opposite.

The Lune valley has now flattened out, giving long

views to the south, east and north. An island (when the

river is high) has been formed, with its shores strewn with

large boulders and tree-trunks washed down in floods.

The riverside fields show evidence of old river channels,

with the lagoons left by the shifting Lune being favourite

haunts of the heron, a bird that, unlike others, rises with

graceful dignity if disturbed and with slow beats of its

wings drifts off to settle in the long reeds where it can

keep a better eye on you than vice versa.

Left: Logs and the Lune at the ‘island’

Left: Logs and the Lune at the ‘island’

Right: The Lune at the ‘island’, with Leck Fell and Ingleborough beyond

This is a magnificent spot for seeing the salmon

leap. Settle on the west bank on a fine autumn day,

at a point opposite the island, where a deep stretch of

Lune runs straight towards you from the north. There

will be little noise, apart from the splashing salmon. If

the salmon should be resting, there will be, apart from

the heron, a display of bird-life such as oystercatcher,

snipe and kingfisher, if you are lucky – and all this with

a backdrop of the Howgills, Leck Fell and Ingleborough.

This beats Ruskin’s View by far!

The 1847 OS map shows that, south of the island,

the Lune swept in a wide curve half the way to Tunstall,

that is, 500m from its present course. All the fields east

and west of the Lune from Kirkby Lonsdale were marked

“liable to flooding”. The Lune floodplain, about 1km

wide and running 15km from Kirkby Lonsdale to Caton,

has all the characteristics of a textbook floodplain. In

normal conditions, the Lune meanders gently among

wide, flat and tranquil pastures, where glacial till and

regular alluvium deposits create rich soils to provide

fertile grazing land for sheep and cattle. Abandoned

channels and protected hollows create lagoons that

are replenished by floods and heavy rain to provide

important wetland habitats for birds, fish and plants.

Kingfishers and sand martins are able to nest in the

eroded riverbanks.

For obvious reasons, there are no human habitations

in the floodplain, increasing the sense that the area is

a haven for wildlife. The floodplain rises gently to its

undulating fringes, where homesteads have been built

and along which important lines of communication have

always existed. Communication across the floodplain

was more difficult, although there were several fords

between settlements on opposite banks. In general, the

Lune is fortunate that, although there has been some

drainage and flood protection work, there has been no

major urban or industrial development to affect these

ecologically important areas of grassland and wet

meadows.

The Lune continues south, to be joined by the major

tributary of the River Greta.

The salmon is the Lune’s jewel. The Lune has one of the

most important populations of Atlantic salmon in England,

salmon being found through much of the Lune’s catchment

area. The eggs are laid in autumn, with the young salmon

staying in their native beck for up to three years. The

mature salmon then spend two or three years in the sea

before returning to their beck in early summer in order to

spawn and then, usually, to die.

The Lune was once one of the best salmon fisheries

in England but numbers dropped in the 1960s because of

disease (ulcerative dermal necrosis, which certainly sounds

bad). There may well have been other factors, such as the

loss of spawning habitats, excessive fishing, poor water

quality, and barriers to the salmons’ swim upstream, as

well as causes external to the Lune. The Lune’s problems

are not unique as global catches of Atlantic salmon fell by

80% in the 30 years from 1970. Although the numbers of

Lune salmon have since revived they are not yet back to

previous levels and the numbers of sea-trout also remain

disappointing.

The Environment Agency now monitors salmon

populations through automatic counters at Forge Bank Weir,

Caton and Broadraine Weir, Killington and has developed

a ‘salmon action plan’ for the Lune. This includes giving

nature a hand by releasing four-month-old salmon fry,

reared from Lune eggs, into upstream tributaries.

[Update: The number of salmon in the Lune has

plummeted, according to recent reports. I'm not an angler but on my casual observations

of the river I rarely hear a salmon splash nowadays (unlike in previous decades) -

and I don't see as many anglers either.]

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Middleton Fell)

The Next Chapter (The Greta Headwaters)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Left: Underley Bridge

Left: Underley Bridge

Right: Underley Hall

Right: Underley Hall

Right: Toll Bar Cottage, Casterton

Right: Toll Bar Cottage, Casterton

Left: St Mary’s Church, Kirkby Lonsdale

Left: St Mary’s Church, Kirkby Lonsdale

Left: The other view from Ruskin’s View, looking to The Island

Left: The other view from Ruskin’s View, looking to The Island

Ease Gill runs from the slopes of Great Coum ...

Ease Gill runs from the slopes of Great Coum ...

... and gradually disappears through limestone ...

... and gradually disappears through limestone ...

... the bed becoming completely dry in places ...

... the bed becoming completely dry in places ...

... though there’s usually a trickle at Cow Dub ...

... though there’s usually a trickle at Cow Dub ...

... below which the valley is dry and quiet ...

... below which the valley is dry and quiet ...

... with eerie grottos and waterless waterfalls ...

... with eerie grottos and waterless waterfalls ...

... meanwhile the underground waters of

Ease Gill are exploring the Easegill Caverns, as

many potholers also do by, for example, entering

Lancaster Hole ...

... meanwhile the underground waters of

Ease Gill are exploring the Easegill Caverns, as

many potholers also do by, for example, entering

Lancaster Hole ...

... and eventually, as the waters reach the

impermeable rock below the layer of limestone,

they re-emerge at Leck Beck Head near Ease Gill

Kirk to form Leck Beck.

... and eventually, as the waters reach the

impermeable rock below the layer of limestone,

they re-emerge at Leck Beck Head near Ease Gill

Kirk to form Leck Beck.

Left: The Leck Beck valley

Left: The Leck Beck valley

Right: Roman stonework in Over Burrow barn

Right: Roman stonework in Over Burrow barn

Left: Logs and the Lune at the ‘island’

Left: Logs and the Lune at the ‘island’