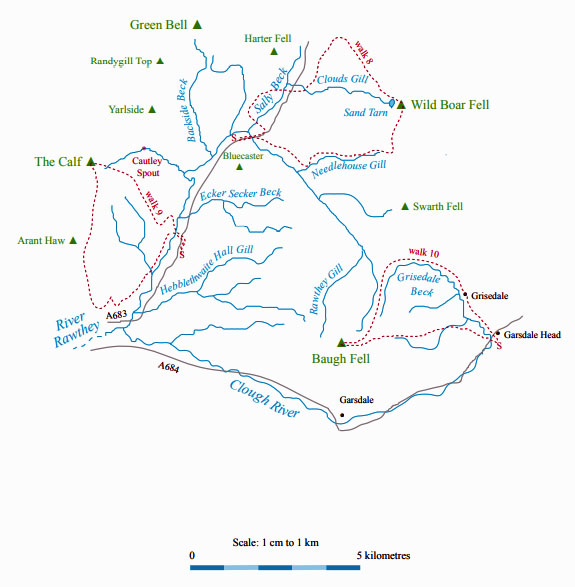

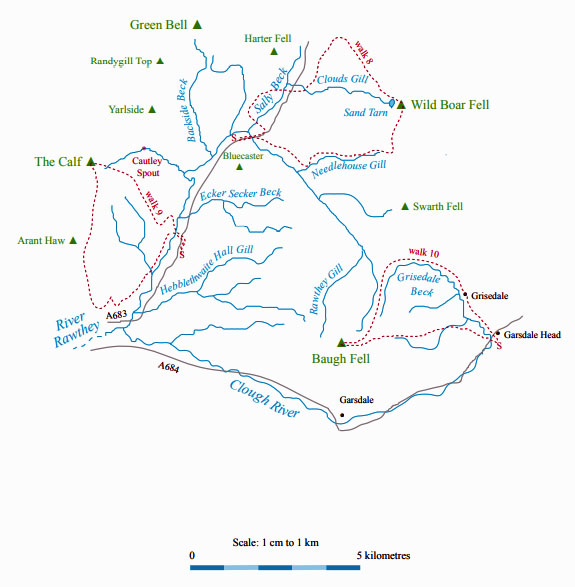

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 4: Upper Rawtheydale

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Western Howgills and Firbank Fell)

The Next Chapter (Lower Rawtheydale and Dentdale)

From Fell End Clouds towards Cautley Crag

The River Rawthey ...

Left: From Baugh Fell over Rawthey Gill to the Howgills

Left: From Baugh Fell over Rawthey Gill to the Howgills

Right: Rawthey (or Uldale) Force

Like the Lune, the Rawthey first flows north (as

Rawthey Gill off Baugh Fell) and then swings west

and south. Baugh Fell is the largest mountain of

Loyne, in terms of volume, that is, not height, occupying

the huge expanse of high ground between the A683, the

A684 and the Rawthey-Grisedale valley. It is one of the

least visited of the peaks of the Yorkshire Dales and

understandably so, because it is surrounded by many

more attractive challenges.

It is pudding-shaped, with the unappealing

characteristic, for a walker, of being relentlessly uphill

from whichever direction you tackle it and of having a top

that is always over the horizon. There is little of interest

above 400m. And when you reach the top, you cannot

be sure that you are there. The trig point at Knoutberry

Haw is, according to the OS map, 2m lower than the

unmarked, gentle summit at Tarn Rigg Hill (678m).

Some would say that Baugh Fell is pudding-textured

too but that is an exaggeration. Yes, it tends to be wet

and there are peat mounds to negotiate but there’s plenty

of grass and the top is a rough, stony plateau. Still, it is

one of those mountains best tackled when the ground

is frozen solid and there’s a layer of snow to hide the

desolation.

Baugh Fell is not the most exciting fell but it does

provide a magnificent view in all directions: circling

from the north Wild Boar Fell, Mallerstang, Great

Shunner Fell, Pen-y-Ghent, Pendle, Ingleborough,

Whernside, Great Coum, the Lakeland Peaks, and the

Howgills. The views of Whernside and Great Coum are

particularly striking. From other directions they appear

unremarkable but from here they have majestic profiles.

After 3km Rawthey Gill turns a left angle, becoming

the River Rawthey, to run through a limestone gorge

and over a series of waterfalls, one of which at least

deserves a distinctive name. Some call it Uldale Force

but Uldale seems to be the area north of Holmes Moss,

with Uldale Gill further north still. What’s wrong with

a simple Rawthey Force? Anyway, the 10m waterfall is

quite the equal of more illustrious waterfalls that we will

meet later.

Left: Needle House barn (spot the dog)

Left: Needle House barn (spot the dog)

Whin Stone Gill, Blea Gill and Needlehouse Gill

(which begins as Uldale Gill) join the Rawthey off the

western slopes of Swarth Fell, which is one of those

underrated hills that suffer by comparison with a near

neighbour (no, not Baugh Fell – Wild Boar Fell to the

north). At 681m, Swarth Fell is higher than the Howgills

and Baugh Fell and, with a flattish top and crags to

the east, has the characteristic shape of the peaks of

the Yorkshire Dales, although it is only half within the

National Park.

Swarth Fell also has the distinction of lying on the

‘national divide’ of England. From its southern ridge,

waters to the east flow (via the River Ure) to the North

Sea and waters to the west flow (via the Lune) to the

Irish Sea. The eastern boundary of Loyne forms the

national divide for about 8km, over Widdale Fell to

Great Knoutberry Hill and Wold Fell.

Right: Lower falls of the Rawthey near Needle House

Right: Lower falls of the Rawthey near Needle House

Needlehouse Gill runs in a narrow valley, over

waterfalls and past caves, by Needle House and

Uldale House, two of a line of farmsteads among the

small conifer plantations on the northern slopes of the

Rawthey. There are actually two rather fine houses at

Needle House and surely the only barn we’ll see with

a belfry. Uldale House farms 2500ha on Baugh Fell

Common and the farmer there, Harry Hutchinson, is

the chair of the Federation of Cumbrian Commoners,

formed in 2003 to help ensure that policy-makers

understand the importance and complexity of farming

on common land. Currently, there is concern that the

Countryside Stewardship Scheme, which pays farmers

to greatly reduce sheep numbers in order to enhance the

environment, will threaten the commons sheep grazing

tradition.

Rawthey Cave, in which have been found human

remains from about 1500 BC, is on the south bank of

the Rawthey, on the slopes of Bluecaster. The old track

across the flank of Bluecaster drops down to the river,

where, as you would expect, there used to be a bridge

– a bridge of some importance, it would seem, since in

1586 Queen Elizabeth wrote to those responsible for its

upkeep saying that “she marvels at their negligence in the

execution of her former orders concerning the rebuilding

of Rawthey Bridge.” Perhaps the word ‘execution’

spurred some action.

The old bridge is no more but there’s a fine newer

one 50m downstream, built in 1820 with a single semi-circular arch. There’s a minor puzzle here. It is said that

two children’s faces were carved in the bridge. There

seems to be space for a rectangular display on the

two sides of the bridge but perhaps the displays have

fallen out. On the west side there is a face, but that of a

bewigged gentleman, it seems to me. On the east side,

there are what, if viewed generously, could be two eyes

and a nose. What it means, if anything, is a mystery.

Just below the bridge the nicely named Sally Beck

enters the Rawthey.

Sally Beck

Sally Beck arises 4km north in the fields above

Studfold. Under normal conditions, it receives

numerous becks flowing from Harter Fell on the west

but nothing at all from Fell End Clouds on the east.

This is because the Clouds are formed of limestone, into

which rainwater disappears.

The limestone does not really form terraces like we

saw on Orton Scar because it is too distorted. It occurs

as small cliffs and scattered, rocky outcrops. There are

two well-preserved limekilns, with evidence of old mine

workings, and in the middle of the Clouds there’s an

intriguing enclosed field containing the ruins of old walls

(shown in the photograph at the beginning of this chapter). The Clouds have been made a Site

of Special Scientific Interest, mainly because of their

flora, which, because the Clouds are heavily grazed, is

largely restricted to the recesses of the grikes. There are,

for example, seventeen species of fern, including the rare

rigid buckler fern, holly fern, and green spleenwort.

To the south of Fell End Clouds, Clouds Gill makes

a brave effort to cross the limestone to reach Sally Beck.

Most of the time it fails but sometimes, judging by the

erosion, it succeeds with a vengeance. It flows from

Sand Tarn, a perhaps unexpected oasis just below the

Wild Boar Fell trig point.

Sand Tarn, with Harter Fell (with its Five Gills) beyond, and beyond that Green Bell, with Randygill Top,

Kensgriff and Yarlside to the left, and with the Lake District hills in the distance.

The Top 10 lakes in Loyne

(Are there 10 lakes in Loyne?)

1. Sand Tarn, Wild Boar Fell

2. Greensett Tarn, Whernside

3. Sunbiggin Tarn

4. Whernside Tarns (could count as four?)

5. West Baugh Fell Tarn (a good view, at least)

6. Kitmere (but can hardly see it)

7. East Tarns, Baugh Fell (another five or more?)

8. Terrybank Tarn

9. Island Pond, Quernmore

10. The Lake, Clapham Beck (but it’s artificial)

(Only just.)

Right: Wild Boar Fell trig point, looking towards Cautley Crag

Right: Wild Boar Fell trig point, looking towards Cautley Crag

At 708m, Wild Boar Fell is the highest hill we have

met so far – and the most dramatic, although admittedly

most of the drama is on the eastern slopes, which are

within the Eden catchment area. The broader, western

slopes drain to the Lune, via the Rawthey.

Wild Boar Fell has a flat top, with many cairns.

Those on the eastern rim provide marvellous views

into Mallerstang and across to the hills of the Yorkshire

Dales. The trig point is on the western edge and provides

a unique viewpoint down onto the Howgills, giving a

wonderful impression of the rolling contours.

Wild Boar Fell is so called because the last English

wild boar fell here, or so it is said. In case you should

be sceptical, we are given a date and perpetrator for the

deed: 1396 and Sir Richard Musgrave of Hartley Castle.

If doubts still remain, then we’re told that his tomb in

Kirkby Stephen church was found to contain a boar’s

tusk. But your clinching counter-argument is that there

are wild boars in England now.

As Clouds Gill passes the limestone it reaches an

appealing high-level road that was the original road but

is now a quiet by-way above the A683. It is open to the

fell, has wide grassy verges, and has a line of farmsteads

most of which are being revitalised as holiday homes.

Cold Keld, for example, offers guided walking holidays.

To the south is Fell End bunkhouse, which is owned by

the Bendrigg Trust, a charity offering outdoor activities

for disabled people. Foggy Hill, however, is a tractor

outlet, judging by the score or more shining new in the

yard. By the road there is a paddock with a signpost

announcing “Quaker Burial Ground”. It is completely

empty (on the surface). This takes the Quaker’s unfussy

approach to burial close to its logical conclusion, which

it would reach if the signpost were removed.

Left: Sally Beck (centre) joining the Rawthey (running from right to left)

Left: Sally Beck (centre) joining the Rawthey (running from right to left)

A farm name of Streetside and one further north of

Street Farm and the name of Bluecaster will provoke

speculation that this is the line of a Roman road. As far

as I know, there is no evidence on the ground for this, but

on the other hand it is certain that the Romans had major

and minor roads, as we do, and it would be surprising if

they did not take a short cut through Rawtheydale to get

between their forts at Brough and Over Burrow.

On the fell opposite there’s a rougher track that goes

up to Sprintgill and Murthwaite, home of the Murthwaite

fell ponies, except that, being semi-wild in the Howgills,

they hardly have a home. Their owner, Thomas Capstick,

is a renowned photographer of fell ponies.

As Sally Beck makes its way to the Rawthey we

might pause to reflect on the significance of what we

have seen on Baugh Fell, Swarth Fell and Wild Boar

Fell. The craggy tops differ from the rounded hills of the

Howgills. They are of millstone grit, below which is a

layer of shale and sandstone above a limestone base. The

limestone gives rise to caves and potholes, which are

absent from the Howgills. Clearly, the geology of Baugh

Fell, Swarth Fell and Wild Boar Fell is different to that

of the Howgills. As we concluded when we similarly

reflected at Orton, we must be on the line of a geological

fault. In fact, this is the line of one of Britain’s most well

known faults, the Dent Fault.

The Dent Fault is the most important geological feature

of the Loyne region. It runs north south for some 30km

roughly between the two Kirkbys (Stephen and Lonsdale),

splitting the northern half of Loyne in two. To the west are

the rounded Howgills of Silurian rock (about 420 million

years old); to the east are the horizontal limestone scars of

the Dales (some 100 million years younger).

The line of the Dent Fault is, of course, not a

hypothetical line like the equator that one might imagine

standing astride. It is a line of weakness in the earth’s

surface that, over a long period about 300 million years ago

and with tumultuous forces, caused the rocks to the west of

it to rise about 2km compared to the rocks to the east. It is

considered the best example in England of a reverse fault

(as opposed to a normal fault, where rocks move down).

In the eons afterwards the western rocks have been eroded

to roughly the same level as the eastern rocks. But along

the fault-line there were and remain complex distortions of

the rocks. This explains also the line of quarries along the

fault, as various exposed minerals were mined.

We will cross the line of the fault again later as we

follow the Clough River, the River Dee and Barbon Beck.

Walk 8: Fell End Clouds, Wild Boar Fell and Uldale Gill

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: A large lay-by on the A683 near Rawthey Bridge (712978).

Cross the bridge, walk 400m along the A683, take the footpath left up to Murthwaite and continue to Sprintgill (with views

of Wild Boar Fell to the right). At Low Sprintgill, drop down to cross the A683 and take the track past the ruins of Dovengill to

reach the by-road. Walk north and 200m past Cold Keld take the track passing between two prominent limekilns. Continue up the

track past the enclosed fields to Dale Slack to reach the fell above the limestone.

Now it is a long, pathless walk to the top of Wild Boar Fell, gently sloped apart from the sharp climb above Sand Tarn.

Aim to the left of the two cairns on the horizon. From the trig point there are views across the rolling Howgills to the Lake

District peaks. Stroll over to the cairns on the precipitous eastern edge and admire the breath-taking view into the Eden valley of

Mallerstang. To the right, you can see Pen-y-Ghent, Pendle, Ingleborough and Whernside.

From Wild Boar Fell head south to the saddle below Swarth Fell, with a small tarn. Turn west to follow Uldale Gill down,

keeping high on the northern bank, to avoid too much up and down. Cautley Crag is straight ahead. Just before Grain Gill joins,

a beck can be seen issuing from a cave halfway up the south bank of Uldale Gill.

After crossing Grain Gill, keep to the right of the wall that takes you southwest. Follow the wall to the right of a small

plantation to reach the road. Turn left and follow the track across Needlehouse Gill. As the path swings down among trees, look

out to the right for a footbridge across Needlehouse Gill (there seems not to be a footpath sign). Cross the footbridge and follow

the footpath that goes through Needle House, New House, Tarn and Wraygreen. Follow the road back to Rawthey Bridge.

Short walk variation: Walk through Murthwaite and Cold Keld to Dale Slack, above Fell End Clouds, as for the long walk. Now

follow the contour south for about 3km to reach Grain Gill and the wall north of Needlehouse Gill. Then follow the last part of the

long walk through Needle House to Wraygreen and Rawthey Bridge. If the walk south along the contour seems to be loo long, it

is always possible to shorten the walk by dropping down west to The Street and following it southwest to Rawthey Bridge.

The Rawthey from Sally Beck ...

As the Rawthey swings south it passes Murthwaite

Park, the only sizable area of ancient woodland in

the Howgills. The scrubby birch, hazel, ash and alder are

still home to red squirrels although perhaps for not much

longer as on two recent occasions I think I glimpsed grey

squirrels as well. But perhaps I am unduly pessimistic:

I understand that the present cull of grey squirrels is

beginning to bring red squirrels back to the Howgills

area.

Many becks from the eastern Howgills and West

Baugh Fell join the Rawthey as it continues south through

luxuriant green pastures. Wandale Beck runs from

Adamthwaite, an isolated farmhouse that has the honour

of being the habitation nearest to the Lune’s source,

just 2km southeast of Green Bell. The next significant

tributary, Backside Beck, runs, appropriately, from the

back side of Green Bell. All the Howgills, therefore,

except for a small part northeast of Green Bell, is within

the Lune catchment area. The farmstead of Mountain

View, above Backside Beck, is abandoned, but what can

you expect of a place called Mountain View? It has to be

something like Cobblethwaite to survive up here.

Wandale Beck and Backside Beck are notable

for exposures of fossil-rich Ordovician and Silurian

rocks along their beds, of great interest to geologists.

According to the Site of Special Scientific Interest

description “the Cautley Mudstones of Rawtheyan age

are of a dominantly dalmanellid-plectambonitacean

assemblage”, which is more than I could ask for.

Looking across Backside Beck from the slopes of Yarlside to Wandale Hill

Within the Rawthey valley there are a few

farmsteads, a garage and the Cross Keys Inn. The inn

was originally a farmstead called High Haygarth (Low

Haygarth continues nearby as a horse-breeding farm). It

is older than the date (1730) newly installed over its door.

An earlier owner’s wife, Dorothy Benson, a Quaker who

had been imprisoned in 1653, was later buried (after she

died, of course) under what is now the dining room. High

Haygarth became an inn in the 1800s, probably after the

road was re-aligned in 1820 to run past it rather than

over Bluecaster. It was converted to a temperance inn in

1902 and left to the National Trust in 1949.

Below the Cross Keys Inn, Cautley Holme Beck

joins the Rawthey from within the great bowl of Cautley

Crag and Yarlside. The becks that run east from The

Calf create Cautley Spout, a cascade of 200m in all,

with a longest single fall of 30m. Some guides assign

various superlatives to Cautley Spout – for example,

that it is England’s highest waterfall. It would take

an odd definition for any such objective claim to be

sound. It is safer to be more subjective, by saying that

Cautley Spout provides the best long-distance view of

any English waterfall – from Bluecaster, for example.

However, from afar, you see only the last of a series of

cascades. The full set can be seen only from the slopes of

the unnamed hill south of Yarlside. Dominated by grass,

the Howgills are generally of little botanical interest

but the Cautley Spout ravine, well-watered, sun-facing

and protected from grazing, has a number of unusual

plant species, such as alpine lady’s mantle, otherwise

restricted in England to the Lake District. Perhaps the

protected bowl around Cautley Holme Beck encouraged

the Iron Age settlements for which, for the only time

within the Howgills, the OS map uses its special font

for antiquities.

Cautley Spout (centre, to the right of Cautley Crag) from Foxhole Rigg

The Top 10 waterfalls in Loyne

1. Cautley Spout, Howgills

2. Black Force, Howgills

3. Rawthey (Uldale) Force

4. Thornton Force, Ingleton

5. Gaping Gill, below Ingleborough

6. Force Gill, Whernside

7. Ibbeth Peril, Dentdale

8. Docker Force, Birk Beck

9. Taythes Gill, Baugh Fell

10. Clough Force, Grisedale

Right: Cautley Crag - and, beyond Cautley Spout, Bowderdale

Right: Cautley Crag - and, beyond Cautley Spout, Bowderdale

Cautley Spout is at the northern end of the 1km cliff

face of Cautley Crag, formed by the erosion of an Ice

Age cirque. The crag face is too unstable to be walked

upon or climbed but it is the most impressive cliff in

the Howgills. At close quarters, the cliff face is less

fearsome than it seems: it is not as vertical as it looks

from a distance and the ominous dark is due to heather,

not rock, which is a pale grey, as the scree slopes show.

The tributary of Ecker Secker Beck, like all the

becks that drain west off West Baugh Fell and cross the

Dent Fault, has eroded deep ravines and formed a series

of small waterfalls as it crosses tilted, fissured rocks.

The unusual exposed rock formations in Taythes Gill are

well worth a visit, even for the amateur geologist. For

the professional, they are essential; for it is here that the

fine detail of upper Ordovician rock (420-440 million

years old) may be unravelled. The trilobite fossils first

found here are used as the standard by which the same

layers are identified elsewhere.

Some expertise is also required to appreciate Ecker

Secker Beck’s other notable feature, the meadows near

Foxhole Rigg that have been made a Site of Special

Scientific Interest because they are a rare example of

unimproved, traditionally managed grassland. The

list of herbs and grasses that grow here reads like the

index to a botanical encyclopedia. If you can tell a hairy

lady’s mantle from an opposite-leaved golden saxifrage,

then this too is worth a visit. Lacking geological or

botanical expertise, we may simply enjoy the views

across to the eastern Howgills, with Cautley Crag

centre stage, and count the great

spotted woodpeckers, which, on

a bright November day, seemed

plentiful.

Further south, where

Hebblethwaite Hall Gill crosses

the Dent Fault, the line of the

fault is indicated by a series of

shakeholes. As these form in

limestone, the fault must run just

to the west of the line of holes. To

the east of the fault, on a plateau

between the rough sheep grazing

land and the green cow pastures,

some of the exposed rock strata

are almost vertical, indicating the

geological stresses of long ago.

Left: Alpaca at Ghyllas, with Knott and Fawcett Bank Rigg beyond

Left: Alpaca at Ghyllas, with Knott and Fawcett Bank Rigg beyond

Hebblethwaite is an ancient

name for the district. A Richardus

and Agnes de Hebletwayt are

listed in the Poll Tax of 1379

and a will of 1587 refers to

“the Mannor or Graunge of

Hebblethwaite”. Hebblethwaite

Mill was built in the 1790s and

was one of the first to use the

new wool carding machines, powered by a water wheel.

The Woodland Trust now manages Hebblethwaite Hall

Wood, which is a 1km long strip of ancient oak and ash

woodland alongside the beck that tumbles in a deep,

dark ravine over many small waterfalls. A permissive

path by the beck provides a short walk, best appreciated

on a winter’s day, when the leaves have fallen.

If you follow the path down from the hall you may

need to rub your sheep-sated eyes as you approach the

farmstead of Ghyllas. What you see are not sheep at

all but alpaca. Ghyllas is leading a Why Not Alpacas?

campaign – and, if the farmers are happy, why not

indeed? Alpacas certainly have more spirit and charm

than sheep. They make a soft humming noise and if

in the mood they orgle (an orgle is a kind of orgasmic

gargle). More to the commercial point, alpaca fibre is

valued for the lightness and warmth it brings to winter

clothing.

Shortly after the Hebblethwaite Hall Gill merger,

the Rawthey passes under Straight Bridge and after a

further 200m, the major tributary of Clough River joins

the Rawthey.

Walk 9: The Calf via Great Dummacks

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: A lay-by opposite St Marks Church (691946).

We have nearly completed our circuit of the Howgills and I have not yet provided a walk to its highest point, The Calf

(676m). Since The Calf is at the centre of the radiating ridges, many walks are possible. The two ‘tourist routes’ (not that there

are many tourists) are from Sedbergh over Winder and from Cross Keys Inn past Cautley Spout. Our expedition is intended to

provide a greater variety of walking than is usual on the Howgills.

Before setting off, note the ridge on the western horizon: that is your immediate objective. Walk 200m north along the A683,

cross the footbridge at Crook Holme, and take the higher of the two paths north to reach the CRoW land. Walk north for a short

distance, past gorse bushes, and then cut diagonally back to reach Fawcett Bank Rigg.

Now it is relentlessly uphill along a grassy ridge but not too steep for comfortable walking. There is no hurry: stop often to

admire Rawtheydale below and Wild Boar Fell beyond. Continue to the edge of Cautley Crag, and not one step further: the best

view in the Howgills is suddenly revealed. Skirt the edge a little distance and then make your way across to the Calf trig point,

visible 1km to the west. This involves a little scrambling up, down and over grass tussocks.

From The Calf follow the main ridge south for 3km to Arant Haw, below which you swing south off the path to Crook

(1km distant), where there is a large cairn. Descend the slope south: it is steep but not too difficult. Look at the fields below and

compare carefully with your map to identify where the public footpath begins: there’s a stile in the corner of the field (666931).

Then take the path northeast through Ghyll Farm, Stone Hall, Hollin Hill, Ellerthwaite, Thursgill and Fawcett Bank (noting

the fine bridge over Hobdale Beck). A further km beyond Fawcett Bank you reach the path back to Crook Holme, the footbridge,

and the starting point.

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk as far as the edge of Cautley Crag. Then turn west over Great Dummacks for nearly

1 km to reach the fence that drops south to Middle Tongue. Continue on the Middle Tongue ridge until you reach the confluence

of Hobdale Gill and Grimes Gill. Cross the latter and continue east to drop down (avoiding gorse bushes) to the track from which

you reach the Crook Holme footbridge.

Clough River

Right: Pen-y-Ghent (far left), Ingleborough and Whernside (to the right) from East Baugh Fell

Right: Pen-y-Ghent (far left), Ingleborough and Whernside (to the right) from East Baugh Fell

Clough River begins to adopt its name at Garsdale

Head, 15km east of Sedbergh, after gathering the

becks that flow off East Baugh Fell and south Swarth

Fell through the secluded valley of Grisedale. We can

regard the westernmost of these becks, Grisedale Gill,

to be its source. Grisedale Gill and Haskhaw Gill set off

north from Tarn Hill on East Baugh Fell a few metres

apart before going their opposite ways, Haskhaw Gill

joining the Rawthey. Their waters then complete semi-circuits of Baugh Fell, before re-uniting near Sedbergh.

The only feature on East Baugh Fell is Grisedale

Pike, where a dozen or so cairns form a prominent

landmark at an excellent viewpoint into Grisedale and

upper Wensleydale. A cairn usually stands alone, as a

guide to shepherd or walker, and so when they occur in

a cluster and presumably had some function beyond that

of mere guide, it is natural to wonder what that function

might have been. The cairns are very old but they seem

not to have had any function such as has been proposed

for standing stones such as Stonehenge. Their position,

at this precise location, surely reflects aesthetic values of

long ago, which are not so different from our own.

Dandrymire Viaduct from Grisedale Pike

As Grisedale Gill swings east it enters The Dale that

Died, as Grisedale was called in a book and television

documentary of that name in the 1970s. In the previous

few decades all but one of the farmsteads in the dale

were deserted and left to fall into ruin, the families

there no longer able to cope with the economic hardship

of farming life. Abandoned and derelict, Grisedale

no doubt enabled a romantic tale to be told of human

struggle against adversity.

But the funeral rites were premature. Not only does

the one remaining farm appear to be flourishing, but also

many of the ruins have been, or are being, revitalised.

For example, Fea Fow is in fine fettle: it is a Grade II

listed traditional farmhouse, built in the 17th century and

renovated to retain many original features, now with a

new role as a holiday cottage.

One may lament the passing of a time when a family

could live off a small patch of land in such an isolated

location. On the other hand, Grisedale is much too fine a

valley to be forgotten. Its fields, all above 350m, provide

a sheltered haven – or even heaven, for those who like

the quiet becks and limestone crags within the high

moors. As long as the new developments are in keeping

with the traditions of Grisedale – as they appear to be –

they must surely be welcomed as Grisedale evolves into

a new role.

Right: A considerate warning on the footpath into Grisedale

Right: A considerate warning on the footpath into Grisedale

After gathering a few more becks from East Baugh

Fell, Grisedale Beck becomes Clough River and passes

over Clough Force, a neat, curved waterfall only 3m or

so high. Just below the A684 the Clough is joined by

Black Gutter, which leaves Garsdale Low Moor heading

purposefully towards Wensleydale only to swing west

at Dandry Mire. According to experts, all the becks that

flow east off Baugh Fell used to join the River Ure but

were blocked by glacial debris and so were diverted west.

At the watershed of Dandry Mire there’s an impressive

12-arched viaduct, which provides our first encounter

with the famous Settle-Carlisle railway line. It is a mire

indeed for the original plan to build an embankment had

to be abandoned when the earth tipped here just sank

into the bog.

The Clough heads west through the valley of

Garsdale, perhaps the least highly regarded of all the

Yorkshire Dales, at least, by tourists. It is a narrow

valley so enclosed by the steep, grassy, featureless

slopes of Baugh Fell and Rise Hill that in winter the sun

can barely reach. The busy A684 runs by the Clough,

crossing it eight times in all.

The conifer plantations in Garsdale have been made

a Red Squirrel Reserve, one of sixteen set up in 2005

by the North of England Red Squirrel Conservation

Strategy. It is thought that the numbers of red squirrels

have increased as the conifers have reached maturity,

providing the cones upon which red, but not grey,

squirrels thrive.

There are a few footpaths in the dale but they cannot

be linked to make a good long walk. Many of them

appear unwelcoming and under-used, giving the walker

the feeling of trespassing. Although the slopes of Baugh

Fell and Rise Hill are CRoW land they are tantalisingly

out of reach above the pastures: a walker must enter at

the eastern or western end and it must be rare indeed

for anyone to find the incentive to walk the slopes

from one end to the other. On a recent occasion when

I walked in Garsdale the A684 was closed because the

Clough had washed some of it away, which was much

appreciated. The footpaths, by-roads and quiet A684

could be combined to provide a rare, blissful experience:

an indication of what Garsdale once was and could be.

Left: A once-fine but now derelict homestead in Garsdale

Left: A once-fine but now derelict homestead in Garsdale

There is not much to cause a tourist to linger,

although rural architecture is always interesting. Some

houses are converted long barns but

many follow the standard design of

three windows up, two down, with

a door and porch between. Dandra

Garth, by the bridleway to Dentdale

and now rather enclosed, has character.

Swarthgill House is startlingly white.

But Paradise (East, West, Middle and

High) is somewhat optimistic.

The village of Garsdale consists

of little more than a row of cottages,

called The Street. There’s a Primitive

Methodist Chapel (1876, when the

Settle-Carlisle line was built), now

a Mount Zion Chapel, at Garsdale

Head, and in the village another

Primitive Methodist Chapel (1841)

and the Anglican Church of St John

the Baptist (1861), next to the site of

a medieval church, and further on a

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel (1830),

and at Bridge End another Wesleyan

Chapel (1868), now a barn, and

at Frostrow yet another Wesleyan

Chapel (1886).

Right: Baugh Fell from lower Garsdale

Right: Baugh Fell from lower Garsdale

Methodism, like Quakerism, had

and has a particular appeal to non-conformist northerners. It is a more

visible presence in Loyne because,

clearly, Methodists, unlike Quakers,

believed in their chapels and the

19th century was a safe time to build

them. Even in the remotest regions we

come across sometimes tiny chapels,

to which itinerant preachers came to

give enthusiastic sermons.

At Danny Bridge, as the Clough

emerges from the confines of Baugh

Fell and Rise Hill, it runs beside the

Sedgwick Trail across the Dent Fault.

A detailed leaflet should be obtained

from Sedbergh Tourist Information

Centre in order fully to appreciate

the significance of the viewpoints but

even without it the transition across

the Dent Fault, from the contorted

Carboniferous limestone to the older

Silurian rocks, should be clear: roughly

where the wood opposite ends there is

an abrupt change from a rocky gorge

within sloping limestone to a shallow,

broad valley with rocks 100m years

older. Above the trail on Tom Croft

Hill there is a fine view of the “naked

heights” (copyright Wordsworth) of

the Howgills. I don’t know who Tom

Croft was but if he lived in Tom Croft

Cave on the Sedgwick Trail he was

exceedingly small.

The Clough runs between the

gentler slopes of Dowbiggin and

Frostrow and, just before it enters the

Rawthey, passes Farfield Mill, an arts

and heritage centre in which a range

of artists (such as weavers, furniture

makers and textile workers) work in

open studios. Built in 1836, it had

functioned as a woollen mill until

it closed in 1992, after which it was

bought and restored by the Sedbergh

and District Buildings Preservation

Trust.

The Settle-Carlisle railway line is the most spectacular

in England. It runs for nearly 120km, with 325 bridges,

21 viaducts and 14 tunnels, on a route through some of

the finest scenery of northern England. It was completed

in 1876, after 6½ years building, at a cost of £3.5m and

many lives. It is regarded as the last great Victorian railway

engineering project.

The 15km of the line that is within Loyne includes

four dramatic viaducts and two long tunnels and is all at a

height of 300m or more, providing fine views of the dales

and hills (except when in the tunnels, of course).

In the 1980s there were plans to close the line: freight

traffic was diverted, passenger services were withdrawn,

and the infrastructure was allowed to decay. However, after

a long, high-profile campaign the line was reprieved, which

pleased tourists and also freight operators, who came to

value it as an alternative to the crowded west coast main

line. In 2005 it found an additional role: to carry six trains a

day bringing coal from Scottish mines to Yorkshire power

stations.

Walk 10: Grisedale and East Baugh Fell

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Near Garsdale Station (787917).

Cross the A684 and take the clearly signposted path to Blake Mire. Continue to Moor Rigg and then follow the road to East

House and the track past Fea Fow to Flust. At Flust take the higher of the two paths, continuing on the contour west. The path

gradually becomes less distinct, as it passes lines of shakeholes.

Note the deep gully of Rawthey Gill ahead: your aim is to reach between the two gullies east of it, Haskhaw Gill and

Grisedale Gill. At that point, it becomes clear that the former flows west and the latter east. There is a cave marked on the OS map

at the strategic point but don’t worry unduly about locating it – it refers to one of the many shakeholes.

So far, it has been a pleasant stroll through the hidden valley of Grisedale but now you must summon the energy to walk up

the watershed between the two gills. Eventually, a cairn will come into view on your right. Keep to the left of the cairn, proceed

to the wall and follow it to the top of Tarn Rigg Hill. The panorama is wide but note especially the view of Whernside, 10km

south.

Return east by the wall for 1km and continue in its line, leaving it as it bends to the right. This takes you directly to the cairns

of Grisedale Pike, with a view of Dandrymire Viaduct and upper Wensleydale.

Aim towards the viaduct and, keeping to the CRoW land, reach Double Hole Bridge. Keep on the right bank of Stony Gill

to pass Clough Force and then, after reaching the road at Clough Cottage, walk back towards Garsdale Station.

Short walk variation: A short walk does not permit the long tramp up Baugh Fell. Instead, we must content ourselves with an

exploration of Grisedale. Follow the long walk as far as Flust and then take the lower of the two paths, to the ruin of Round Ing.

Then turn east to return via West Scale and East Scale to the road at Moor Rigg. From here you could return the way you came,

or follow the road (very little traffic) over Double Hole Bridge for 2km to the Old Road and then cross the A684 at Low Scale,

returning via High Scale.

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Western Howgills and Firbank Fell)

The Next Chapter (Lower Rawtheydale and Dentdale)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Left: From Baugh Fell over Rawthey Gill to the Howgills

Left: From Baugh Fell over Rawthey Gill to the Howgills

Left: Needle House barn (spot the dog)

Left: Needle House barn (spot the dog)

Right: Lower falls of the Rawthey near Needle House

Right: Lower falls of the Rawthey near Needle House

Right: Wild Boar Fell trig point, looking towards Cautley Crag

Right: Wild Boar Fell trig point, looking towards Cautley Crag

Left: Sally Beck (centre) joining the Rawthey (running from right to left)

Left: Sally Beck (centre) joining the Rawthey (running from right to left)

Right: Cautley Crag - and, beyond Cautley Spout, Bowderdale

Right: Cautley Crag - and, beyond Cautley Spout, Bowderdale

Left: Alpaca at Ghyllas, with Knott and Fawcett Bank Rigg beyond

Left: Alpaca at Ghyllas, with Knott and Fawcett Bank Rigg beyond

Right: Pen-y-Ghent (far left), Ingleborough and Whernside (to the right) from East Baugh Fell

Right: Pen-y-Ghent (far left), Ingleborough and Whernside (to the right) from East Baugh Fell

Right: A considerate warning on the footpath into Grisedale

Right: A considerate warning on the footpath into Grisedale

Left: A once-fine but now derelict homestead in Garsdale

Left: A once-fine but now derelict homestead in Garsdale

Right: Baugh Fell from lower Garsdale

Right: Baugh Fell from lower Garsdale