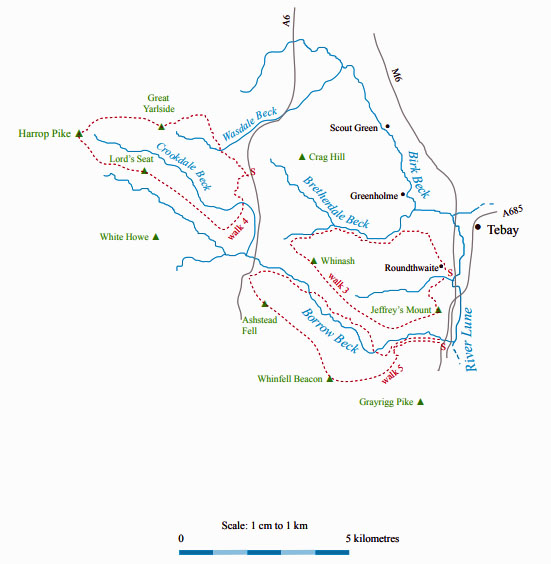

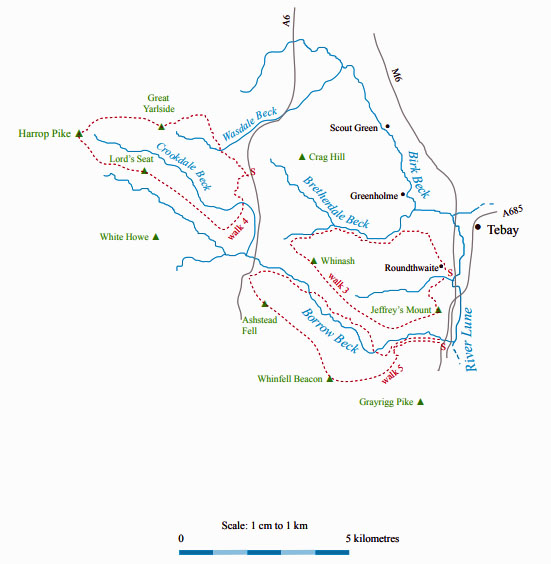

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 2: Shap Fells and Birkbeck Fells

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Northern Howgills and Orton Fells)

The Next Chapter (Western Howgills and Firbank Fell)

Upper Borrowdale from High House Bank

Birk Beck

Left: Wasdale Beck below Shap Pink Quarry

Left: Wasdale Beck below Shap Pink Quarry

Right: Sheep and ruin by Eskew Beck

Birk Beck arises in Wasdale, as Wasdale Beck,

below Great Yarlside, which at 598m and 14km

from the junction with the Lune is only a little

lower and nearer than Green Bell. The most prominent

feature of this region is the cliff face of Shap Pink Quarry,

the existence of which tells us that there are locally rare

and valued rocks. There is an exposure of ‘Shap granite’,

an igneous rock with, amongst many other minerals,

crystals of orthoclase feldspar (potassium aluminium

silicate) so large that they may be studied with the naked

eye. Large pink boulders can be seen in the surrounding

fields and, as we saw, some made their way to the stone

circle near Orton.

The Shap granite is an uprising of the granite that

underlies the Lake District. It is seen in the western

Lakes around, for example, the more famous Wasdale.

This prompts consideration of how our Wasdale relates

to the Lake District. The Shap Fells are officially part

of the Lake District National Park, the eastern border of

which is the A6, but lovers of Lakeland tend to ignore

them. For example, Wainwright’s classic seven volumes

on Lakeland include a volume on the Eastern Fells and

another on the Far Eastern Fells but still do not go far

enough east to include the Shap Fells.

He argued that the Lakeland fells are “romantic in

atmosphere, dramatic in appearance, colourful, craggy,

with swift-running sparkling streams” but that the Shap

Fells have a “quieter and more sombre attractiveness”.

But then Wainwright loved a scramble: anywhere where

it was possible to settle into a brisk walking rhythm was

usually described as dull or tedious. Rather ironically,

the fact that the Shap Fells are in the National Park is

now being used to try to extend the boundary yet further

eastwards to include similar terrain.

[Update: The 2016 changes to the National Park boundaries

did indeed move the eastern border even further east, to the M6 rather than the A6, thus including

the Birkbeck Fells, Bretherdale and lower Borrowdale.]

Right: Docker Force (Birk Beck may be only a tributary of the Lune but up to this

point the Lune has been tame in comparison)

Right: Docker Force (Birk Beck may be only a tributary of the Lune but up to this

point the Lune has been tame in comparison)

South of the granite intrusion, the Shap Fells

bedrock is of the Silurian slates and grits that underlie

the Howgills. Here, however, deep peat gives blanket

bog, with some heather moorland. The variety of upland

vegetation supports breeding waders (curlew, lapwing,

redshank, snipe) and raptors (peregrine falcon, merlin),

although not very many, as far as I have seen. There’s

also a herd of red deer.

The headwaters of Wasdale Beck run off the slopes

of Great Yarlside and Wasdale Pike, heading northeast

to meet Longfell Gill, which passes the brother quarry,

Shap Blue Quarry, which mines darker shades of granite.

At the junction is Shap Wells Hotel, built in 1833 for

visitors, including royalty, to the nearby Shap Spa.

The beck, now called Birk Beck, passes Salterwath,

a farmstead that lends its name to Salterwath Limestone.

This first came from quarries 1km to the east, now

beyond the railway and motorway, and more recently

from Pickering Quarry 4km north. The limestone, which

is blue-grey when quarried and polishes to a brownish

shade, is a fine building and paving stone.

Below the 5m waterfall of Docker Force, Stakeley

Beck and Eskew Beck join Birk Beck off Birkbeck Fells,

a dull triangle of common land between the A6, M6 and

Bretherdale, heathery to the north and grassy to the south.

There’s a good path from Ewelock Bank to the highest

point, Crag Hill (400m), but the top is disappointing as

it is little higher than nearby hillocks, lower than the A6

and surrounded in all directions by higher fells. Still, it

provides reasonable views of those fells, especially the

Cross Fell range and the Howgills.

Birk Beck runs past the small, secluded communities

of Scout Green and Greenholme. It is hard to imagine

now that they once lay on the route of an important

drove road. Then, when there was no M6 or railway, it

would have been quiet enough to hear the approaching

clamour of a thousand cattle and accompanying

throng; at the villages, excitement would grow –

perhaps the visit coincided with a local market,

with a lively exchange of beasts; the drovers

would eat and drink (it was thirsty work); maybe

the cattle would be penned overnight; and then

the whole procession would move on to the next

stop a few miles along.

The drove roads were, of course, not roads

as we know them. They were wide tracks, often

on high ground, partly for the free grazing there

and partly to avoid the risk of ambush. A drover

was a person of prestige and responsibility.

The annual pilgrimage of cattle from Galloway

to the south for sale or for fattening in the

milder climate occurred for centuries before

the railways made the practice obsolete. The

drove roads were not restricted to cattle: they

became the standard route of passage for people

transporting other essentials of life, such as

wool, coal and salt.

Surviving drove roads are characterised by

their wide margins. The routes of the Galloway

Gate (the name of the drove roads between

Scotland and northwest England) through Loyne

can be traced by place names (e.g. Three Mile

House, reflecting the typical distance between

stops) and inn names (e.g. Black Bull, Drover’s

Arms). The Galloway Stone, a large Shap

granite boulder north of Salterwath, probably

had significance for drovers.

More recently, Scout Green and Greenholme

became known to railway enthusiasts as locations

to view trains struggling up from Tebay to Shap.

South of Greenholme, at Dorothy Bridge, Birk

Beck is joined by Bretherdale Beck.

Bretherdale Beck

Bretherdale Beck runs between the A6 and M6 in the

valley of Bretherdale, which was quiet and ignored

until it came into the public limelight after a proposal to

erect 27 wind turbines, 115m high, in a 6km by 2km area

on its southern ridge. The proposal for what came to be

called the Whinash Wind Farm was eventually rejected

by the Secretary of State in 2006 because “the Whinash

site is an important and integral part of a far-reaching

landscape which is highly sensitive to change”.

Left: Derelict Parrocks in upper Bretherdale

Left: Derelict Parrocks in upper Bretherdale

The proposal for what would have become England’s

largest land-based set of wind turbines became a test

case for the conflict between protecting the landscape

and securing renewable energy. Many factors provoked

heated debates – too many to summarise here – but

one that, judging from the 127-page inspector’s report,

seems to have been decisive is that the wind turbines

would have impacted on views from the Lakes and Dales

National Parks, from Orton Fells, and from locations

further north. So, the views of Whinash were apparently

more important than the merits of Whinash itself.

It is difficult to argue for those merits: “People love

Bretherdale for its wild, open solitude” … “But nobody

ever goes there” … “But if they did they’d love the

solitude.” How bleak and empty does a region have to be

to be appreciated for that very bleakness and emptiness?

How much intrusion can an empty region absorb before

losing its emptiness? This is an argument not just for

Bretherdale: many parts of Loyne appeal because so few

people go there.

The proposers argued that the wind turbines would

increase the number of visitors to the area. The head of

onshore wind for the British Wind Energy Association

expressed incredulity that anyone should wish to visit

other than to see the turbines: “You’re not going to get

visitors within earshot of the M6 any other way. It’s

barren moorland. Why would people want to walk there

otherwise?”

The debate about Whinash was obfuscated by

opinions that the National Park boundaries might or would

soon change. In particular, some professed to believe

that the Birkbeck Fells, Bretherdale and Borrowdale

were about to become part of the Lake District National

Park – and of course it is unthinkable to have wind

turbines in the Lake District. At the moment, the Lake

District is ringed with wind turbines but there are none

within its boundaries. On the other hand, the proposal,

if approved, might have prevented the Birkbeck Fells

joining the Lake District or might have set a precedent

for further wind turbines in the Lake District.

[Update: As said in the update above, the

Birkbeck Fells, Bretherdale and lower Borrowdale are now within the National Park.]

Right: Lower Bretherdale, looking west

Right: Lower Bretherdale, looking west

A further issue was that all but three of the proposed

27 turbines would have been on common land, which

raised the question of possible interference with the

rights of commoners. Much of the higher land of Loyne

remains as traditional common land but its legal position

is muddled. All common land belongs to an owner (here

the Lowther Estate) not to the commoners. It is the

owner’s prerogative to make proposals about the land.

While the commoners argued that there would be a loss

of grazing rights the inspector did not agree with them.

In fact, he considered that the commoners would benefit

from easier access along the new tracks.

Among those who contributed to the debate were

long-established groups such as Friends of the Earth

and English Nature and newly created ones such as

Friends of Bretherdale. Bretherdale never knew it had

so many friends. The valley today has many abandoned

farmsteads, which visitors, if there are any, might find

charmingly derelict. But each of them was the home,

perhaps for centuries, of families that were forced, in

despair, to abandon their houses and their livelihoods.

Where were the friends when these families needed

them? Are a few wind turbines so much more important

than the ruination of people’s lives? Again, these are

questions not just for Bretherdale. Loyne is and always

has been predominantly rural and many communities

continue to struggle to find a role in the 21st century.

As far as Bretherdale is concerned, all is far from

lost. Although it may be too late for higher Bretherdale,

except perhaps some buildings of Bretherdale Head,

from Midwath Stead downstream there has been some

reinvigoration. For example, Bretherdale Hall has been

renovated despite uncertainty about the wind turbines.

Midwath Stead itself seems a lively group of homesteads,

with, according to its sign, “free range children”.

Overall, it is a pleasant, sheltered valley, with rocky

outcrops on the surrounding hills and an unobtrusive

conifer plantation with other natural woodlands.

Below Midwath Stead some of the fields are, like those

near Raisbeck, traditional unploughed meadows and

consequently rich in grasses, herbs and flowers.

After the Bretherdale Beck junction, Birk Beck

proceeds uneventfully for 2km past Low Scales farm

and under the three-arched Birkbeck Viaduct to join the

Lune.

The Lune from Birk Beck ...

Left: The Lune Gorge from Great Coum, Grayrigg

Left: The Lune Gorge from Great Coum, Grayrigg

Right: Lune’s Bridge

At their junction Birk Beck and the Lune are much

the same size and if the matter hadn’t been pre-empted by the naming it might have been unclear

which was the tributary. They meet head on and as a

significant, placid river run south, heading for a narrow

gap, extravagantly called the Lune Gorge, between steep

hills. This gap is an obvious transport corridor, as the

Romans recognised with their road from Carlisle and

as the drovers appreciated in the Middle Ages. More

recently, the A685, the railway and the M6 motorway

have squeezed themselves into the gap but only after it

had been widened by blasting away the side of Jeffrey’s

Mount.

The lines of transport jostle the Lune for space.

Within 3km, the Lune is crossed nine times: four times by

the M6, twice by the railway, once by the A685 and twice

by footbridges. This is not the most soothing section of

the Lune. Visually, the Lune is pleasant, running over a

wide stony bed, bleached white in summer. Aurally, the

M6 dominates.

Sadly, there is no space left for National Cycle

Route 68 (the Pennine Cycleway), England’s longest

leisure cycle route, which was opened in 2003 and runs

for 570km between Derby and Berwick-on-Tweed.

Within Loyne it runs from Orton to Sedbergh, through

Dentdale, and on to Ingleton and Clapham. Here it is

forced to share 1km with the A685. The cycleway is

described as 20% traffic-free trails and 80% quiet lanes

and minor roads. The A685 is neither.

The Lune is joined from the west by Roundthwaite

Beck, which runs from Roundthwaite Common. The

beck passes Roundthwaite Farm, which is the home of

the Lunesdale fell ponies, about forty of which browse

the fells between Bretherdale and Borrowdale. The

Lunesdale ponies have roamed the common since the

stud was established in 1958 and have become known

as a prize-winning breed. For example,

in 2008 Lunesdale Lady Rebecca was

Supreme Champion at the Fell Pony

Society Breed Show.

Fell ponies are hardy, strong,

active, versatile, stubby, sure-footed

horses, usually black but sometimes

grey, brown or bay. They are on the fells

all year. The fell pony originated on the

moors of northwest England and is one

of nine native breeds in Britain. It was

used as a draught animal and packhorse

since Roman times and was the main

form of transport during the Border

conflicts. The passing of these roles led

to a severe decline in numbers, only

arrested recently by its popularity for

leisure and competitive riding, although

it is really a working breed. The fell

pony is still listed as endangered by the

Rare Breeds Survival Trust.

Tucked between the M6, railway

and A685 bridges is the first distinctive

bridge across the Lune, Lune’s Bridge.

A document of 1379 refers to a

“Lonesbrig” here but the present bridge

is of the 17th century or later. This

attractive bridge is perched across rocks

where the Lune narrows. There are two

arches, the smaller one so high that the

Lune can surely never reach it. Today,

the bridge leads to a memorial stone for

four rail track workers who were killed

near here in 2004 by a runaway trailer

from Scout Green.

The Lune runs through a calm,

open section that once was a quiet

haven between steep hills, and is joined

from the west by the sizable tributary of

Borrow Beck.

The M6 motorway in the Lune Gorge cannot be ignored

so let us try to make a virtue of necessity: it is, after all, the

recipient of a Civic Trust award, the plaque (which was

in the A685 lay-by below Grayrigg Pike until removed

or stolen in 2008) saying “This award for an outstanding

contribution to the appearance of the Westmorland

landscape relates to the 36 miles of M6 Motorway between

the Lancaster and Penrith bypasses”. This contribution will

not be appreciated at the level of the Lune. Distance lends

enchantment and you really need to view the M6 from

Grayrigg Pike, Blease Fell, Linghaw or even further away.

The A6 route via Shap, reaching 424m, was notorious

for its bad visibility and winter conditions. The 1962 report

on the proposed Lancaster-Penrith M6 route whittled the

possibilities down to three: the A6, the Lune Valley, and

the Killington routes. Of the two Lune Gorge routes, the

Killington route was preferred to the Lune Valley (phew!),

although a cost-benefit analysis found the A6 route better

than both. The Killington route was selected because of the

A6 weather problems and because the necessary tunnels

would have “placed restrictions on the movement of

dangerous goods” (?).

So Killington it was. The design and engineering

problems were immense. The A685 was re-aligned; long

constant gradients were designed, reaching a maximum

height of 315m; 77 bridges were needed (plus three for

the A685) – and all intended to blend into the landscape.

Construction began in 1967 and the motorway opened in

October 1970. By now millions of travellers on the M6

have admired the Howgills, but how many of the few of us

on the Howgills have admired the M6?

The Lune below Jeffrey’s Mount

Walk 3: Roundthwaite Common and Bretherdale

Map: OL19 and OL7 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Roundthwaite, where the bridleway to Borrowdale swings southwest (609033).

This is a walk over the area that might have been sacrificed for the Whinash Wind Farm. Follow the bridleway southwest

and immediately after the gate, take the path half left directly up the slope to Jeffrey’s Mount. Continue beyond the small pile of

stones at the top for a little way in order to rest while watching the busy motorway traffic far below.

When you are ready, head west along the ridge over half a dozen gentle rises, including Casterfell Hill, Belt Howe,

Winterscleugh and the highest point, Whinash (471m). In places there is a path but it doesn’t matter much as there are no fences

and it is easy going on grass, with good views into Borrowdale. Almost certainly, Lunesdale fell ponies will be seen on the

common.

When you reach Breasthigh Road, an ancient, deeply grooved track over the ridge, follow it to the right. At Bretherdale

Beck you might like to detour north briefly to see the derelict Bretherdale Head. Follow the quiet road to picturesque Midwath

Stead, with its small bridge.

Continue along the road (very little traffic) past Bretherdale Hall, and then take the footpath through Bretherdale Foot and

Dyke Farm (where the owner assured me that there will soon be signs to help you locate the path) to Pikestone Lane. Turn right

on the lane and walk for 2km to Roundthwaite.

Short walk variation: Between Belt Howe and Breasthigh Road there is no way off the fell to the north and so the only short walk

possible is to follow the long walk up Jeffrey’s Mount to Belt Howe and then take the bridleway back to Roundthwaite. If this

walk is a little on the short side for you, you could continue on the CRoW land over Roundthwaite Common as far as you wish

and perhaps drop down to the bridleway via the Blea Gill waterfalls.

Borrow Beck

Borrowdale Head from High House Bank

Right: The wall from Great Yarlside to Little Yarlside

Right: The wall from Great Yarlside to Little Yarlside

Borrow Beck runs for 10km east from between

High House Fell and Bannisdale Fell through

Borrowdale, the most beautiful valley in Loyne despite

being split in two by the A6. Upper Borrowdale is within

the Lake District National Park and has some of the

character of Lakeland valleys. Unfortunately, there is

no footpath in upper Borrowdale, which therefore can

only be appreciated by walking the long, grassy ridges

on either side.

[Update: All of Borrowdale is now within the

Lake District National Park.]

Just below High Borrow Bridge, Crookdale Beck

joins Borrow Beck. This junction illustrates the difficulty

of determining the source of a watercourse. Upper and

lower Borrowdale are aligned so well that it seems

obvious that the same beck, Borrow Beck, flows through

them both. But Crookdale Beck has a much higher and

more distant source, below Harrop Pike (637m), than

Borrow Beck and at the junction ought to be regarded as

the senior partner.

Perhaps aesthetics play a part because Crookdale

is such a dreary valley that no beck would want to be

born there. There are twelve million visits to the Lake

District National Park each year and approximately none

of them involve an outing to Crookdale. Above Hause

Foot, there is little of interest to a visitor not fascinated

by varieties of grass and herb, only the modest crags of

Great Yarlside breaking the monotonous, peaty slopes.

Hause Foot is on the turnpike route before the A6

was built in the 1820s. A steep curve up the northern

slope can be traced, reaching 440m, with the route

continuing north over Packhorse Hill and south to High

Borrow Bridge. This route played a key part in the 1745

incursion of Bonnie Prince Charlie. When his army

began to retreat, bridges such as High Borrow Bridge

were demolished ahead of it to hamper its struggle over

the Shap summit, after which the Scottish army was

defeated in its last battle on English soil.

In a lay-by on the A6 there is a memorial to drivers

over the A6 Shap summit, but the A6 is far from forgotten

and unused today. There is no memorial to the souls

who tackled the turnpike route. It too is not unused as it

forms part of the 82km Kendal to Carlisle Miller’s Way

footpath, opened in 2006.

Walk 4: Upper Borrowdale, Crookdale and Wasdale

Map: OL7 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: A lay-by at the A6 summit (554062).

As we have Loyne becks from the Lake District, we must have a walk within the Lake District! This is a long, arduous,

isolated walk over grassy and sometimes boggy ridges.

Go west through a gate and under two lines of pylons to reach the old turnpike route. Go south through two gates and at the

third follow the wall down to Crookdale Beck. Cross it and head up High House Bank. At a small cairn there’s a good view into

Borrowdale.

Follow the ridge west. A faint path becomes clearer after Robin Hood, where a good cairn marks another viewpoint. Continue

to Lord’s Seat. Sadly, there is no sight from here of the fine cairn on Harrop Pike to inspire you, but make your way northwest

around crags and peat-mounds (there is no path). Keep well to the left so that you can use the fence to guide you to the top.

After all this effort, the view of the Lakeland hills is disappointing. Only Black Combe, the Coniston range, and a glimpse of

Harter Fell and High Street can be seen beyond the nearer hills. There’s also a view into Mosedale and Sleddale, where you may

be lucky to see red deer. No lakes can be seen apart from a bit of Wet Sleddale Reservoir to the northeast. The view eastwards is

better: a panorama from Morecambe Bay to Cross Fell, with the Howgills prominent.

From Harrop Pike, follow the fence east to Great Yarlside (easy walking here). At the junction follow the fence left, not the

wall right. Follow the right fence at the next junction. After a short while, a plantation comes into view half right. Make a beeline

(no path) across Wasdale, with Shap Pink Quarry to your left, to the right hand corner of the plantation and then across the field

to the lay-by.

The reward for this walk is that you can afterwards boast to Lake District fans that you did Borrowdale and Wasdale in one

day.

Short walk variation: It is possible to have a shorter walk but not really a short walk, once you embark on Crookdale. You could

forgo the pleasure of reaching Harrop Pike by contouring round from Lord’s Seat to Great Yarlside – but don’t cut directly across

Crookdale, as it’s a bog. From Great Yarlside, you could avoid walking in Wasdale by following the wall over Little Yarlside.

Lower Borrowdale, above the farm of Low Borrowdale

Right: Whinfell aerial and repeater station

Right: Whinfell aerial and repeater station

Below High Borrow Bridge, Borrow Beck enters

lower Borrowdale, a serene valley enclosed by steep,

grassy slopes, with occasional rocky outcrops, the

ridges on both sides undulating over a series of gentle

summits reaching almost 500m. The farmstead of High

Borrowdale was derelict for many years until bought in

2002 by the Friends of the Lake District, perhaps as a

ploy to help prevent the building of wind turbines on

Whinash. Many saplings have been planted beside the

beck and the barns have been restored but the farmstead

itself remains a ruin, now tidy rather than derelict.

Low Borrowdale continues to farm the lower valley

in splendid isolation although it was sold in 2008 to

Natural Retreats, a Manchester-based company that

aims to build luxury holiday ‘eco-parks’ alongside all

fourteen national parks. To nobody’s surprise, a planning

application duly followed: to build 29 timber lodges and

7 holiday cottages. This would, of course, disturb the

serenity of the dale, although Natural Retreats naturally

claims otherwise. The application, which is opposed by

the neighbours, the Friends of the Lake District, was

rejected by Eden District Council in 2009, which, it is to

be hoped, should be the end of the matter.

It is a merciful mystery that Borrowdale has escaped

significant change for so long. The Romans and the

drovers did not find use for an east-west path through

Borrowdale but it is surprising that a road joining the Lune

valley and the A6 was never contemplated. Although the

planners’ suggestion that Borrowdale become a reservoir

and the recent Whinash Wind Farm proposal were both

thwarted, the southern ridge, Whinfell, has been less

successful in avoiding modern intrusions. Historically,

Whinfell had a beacon to warn of Scottish invasions and

it is perhaps to be expected that the ridge should now

be adorned with its 21st century equivalents, a repeater

station and aerial. I actually rather like them. Not in

themselves attractive, they enhance their surroundings

(rather like Marilyn Monroe’s beauty spot).

Walk 5: Lower Borrowdale

Map: OL19 and OL7 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Where a side-road leaves the A685 for Borrowdale (607014).

Walk west along the road that skirts Borrowdale Wood until it becomes a track and after a further 0.5km (at 594014) take a

path leading south up through a sparse, old woodland. Eventually, views into Borrowdale open out and the repeater station, with

the aerial to the left, comes into view.

From the repeater station, walk to Whinfell Beacon (good view over Kendal), Castle Fell, Mabbin Crag and Ashstead Fell.

The cairns on the peaks can be seen ahead and the footpath is clear except for a short section in the plantation below Mabbin Crag.

From Ashstead Fell, drop down towards the A6 and take the path northeast to Borrow Beck. Walk east on the south bank for 2km

and cross the bridge leading to High and Low Borrowdale. Continue back by Borrowdale Wood.

Those of boundless energy may extend the walk into a ridge horseshoe by walking up Breasthigh Road (by fording Borrow

Beck or, if that is not possible, crossing it at Huck’s Bridge) to the ridge above Borrowdale Edge, dropping down the bridleway

to Low Borrowdale.

Walks may equally well start at the A6 end, where there are two lay-bys close by Huck’s Bridge.

Short walk variation: Any walk along the length of the Whinfell ridge cannot be considered a short walk. Shorter walks than

the above can be devised by noting carefully the positions of the two bridges, the plantations and the other footpath (from

Roundthwaite) into the valley, and the extent of CRoW land. There are crags on the valley slopes but, if necessary, they can be

negotiated with care. The best and least risky route is to follow the long walk as far as Whinfell Beacon, to proceed to the wall

gate on the way to Castle Fell, and then to turn right to Shooter Howe. A modest scramble will bring you down to Borrow Beck,

which you then follow east.

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Northern Howgills and Orton Fells)

The Next Chapter (Western Howgills and Firbank Fell)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Left: Wasdale Beck below Shap Pink Quarry

Left: Wasdale Beck below Shap Pink Quarry

Right: Docker Force (Birk Beck may be only a tributary of the Lune but up to this

point the Lune has been tame in comparison)

Right: Docker Force (Birk Beck may be only a tributary of the Lune but up to this

point the Lune has been tame in comparison)

Left: Derelict Parrocks in upper Bretherdale

Left: Derelict Parrocks in upper Bretherdale

Right: Lower Bretherdale, looking west

Right: Lower Bretherdale, looking west

Left: The Lune Gorge from Great Coum, Grayrigg

Left: The Lune Gorge from Great Coum, Grayrigg

Right: The wall from Great Yarlside to Little Yarlside

Right: The wall from Great Yarlside to Little Yarlside

Right: Whinfell aerial and repeater station

Right: Whinfell aerial and repeater station