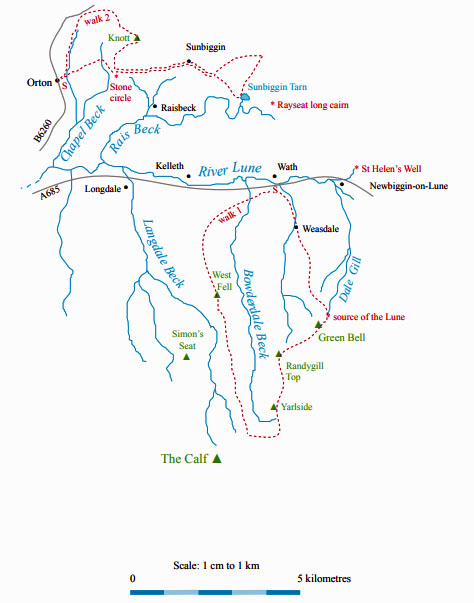

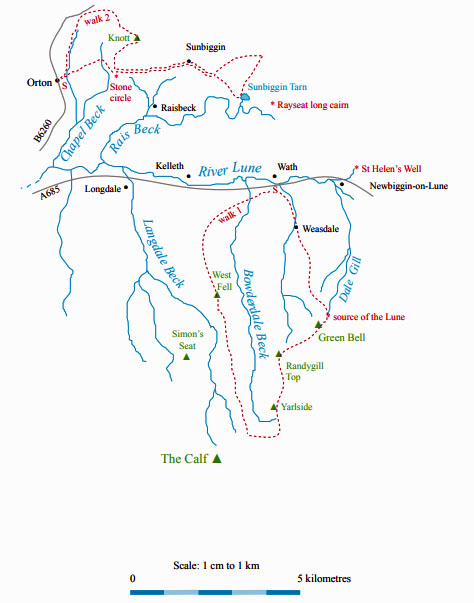

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 1: Northern Howgills and Orton Fells

The Introduction

The Next Chapter (Shap Fells and Birkbeck Fells)

Green Bell trig point, looking over Weasdale

The River Lune ...

Left: The view north standing at the source of the Lune on Green Bell

Left: The view north standing at the source of the Lune on Green Bell

Right: The Lune near Wath (Green Bell in the distance)

A great oak may grow from a single acorn but great

rivers need very many sources. For some reason,

we like to distinguish one of these as the source

of the river, although there are no agreed rules for doing

so. The determination of the source of the Lune has been

made easy for us by the fact that its name continues far

upstream along one particular branch among its many

headwaters, to the helpfully named village of Newbiggin-on-Lune, 9km east of Tebay.

Above Newbiggin-on-Lune, various becks run

north off Green Bell to form the infant Lune. Of these

the longest and highest is Dale Gill, arising from a spring

200m northeast of the Green Bell summit (605m). Since

any rain falling just north of Green Bell will drain into

the Lune we may regard Green Bell itself as our sought-for source. Green Bell is an appropriate name for the

rounded, grassy hill but then so it would be for most

of the fifty or so other named summits in the Howgills.

Green Bell, however, is rightly honoured with a trig

point, one of only four in the Howgills (the others being

at Winder, Middleton and The Calf).

Dale Gill runs 4km north from Green Bell, changing

name twice (to Greenside Beck and Dry Beck), to

become the Lune at Newbiggin-on-Lune. Here, Bessy

Beck joins the Lune after refreshing the three lakes of a

trout fishery. Bessy Beck may be named after Elizabeth

Gaunt of Tower House, near Brownber

Hall, who in 1685 gained the dubious

distinction of being the last woman

to be burned at the stake in England.

Although she may now be regarded

as a virtuous, charitable lady only

too willing to help those in need, the

fact seems to be that she knowingly

helped someone involved in a plot to

assassinate Charles II. The penalty for

high treason duly followed.

Newbiggin-on-Lune is spread

out along what is now a large lay-by,

bypassed by the A685 but not by far enough, as it is

quite noisy. At the eastern end of Newbiggin-on-Lune

is the old St Helen’s Well, which some people insist is

the source of the Lune, because it is never dry, unlike

the Green Bell springs. As this would add dignity to the

Lune’s birth, it deserves investigation. I was informed

at the Lune Spring Garden Centre that the well lies

just across the A685 behind the chapel. The chapel, it

transpires, is a small mound and the well just a seepage

in the field, which is most uninspiring compared to the

slopes of Green Bell.

The fledgling Lune turns west and after 2km reaches

Wath, which most on-line encyclopedias assert is the

start of the Lune, at the confluence of Sandwath Beck

and Weasdale Beck. This seems absurd, as we have

already passed Newbiggin, which insists it is on-Lune.

The appendage, however, is a new one: the 1861 OS

map has a simple Newbiggin. But the old map considers

the stream, which the encyclopedias regard as Sandwath

Beck, resulting from the merger of becks east of Wath to

be the River Lune, as I have done.

Weasdale Beck, equal in size to the Lune at this

point, runs north from near Randygill Top (624m)

through the fine, deep valleys of Weasdale and Great

Swindale. These valleys, however, are not as fine as

the adjacent, parallel Bowderdale, through which flows

Bowderdale Beck to join the now undisputed Lune 1km

below Wath.

The Howgills is the name given to the homogeneous

group of hills in the triangle of about 100 sq km between

Ravenstonedale, Sedbergh and Tebay (or between the

A685, the A683 and the Lune valley).

The hills are well drained, rounded and grassy, with

no bogs and little heather. There are no walls above the

pastures and only one fence. There are significant rocks

in only two places, Cautley Crag and Carlin Gill. So, the

Howgills is a place for striding out along the ridges – but

not across them for then you would have steep eroded

slopes to contend with.

The highest point is The Calf (676m), from which

the ridges radiate to over twenty further tops above 500m.

Walking is easy and airy but, according to Walking Britain

(2005), edited by Lou Johnson, “the Howgills have little

interest underfoot … The reward for scaling the heights

comes from the superb views of the Northern Pennines, the

eastern fells of the Lake District, and the higher peaks of

the Yorkshire Dales”.

This, however, is the wrong frame of mind for tackling

the Howgills. The Howgills must be appreciated on their

own merits. There is no need to be envious of the other peaks

(yes, the views are good but a little distant to be “superb”).

As often the case, Harry Griffin captured the required

spirit best in one of the last of the Country Diary vignettes,

usually about the Lake District, that he contributed for over

fifty years to the Guardian: “the Howgill Fells have always

entranced me. Compared with Lakeland, overrun by the

hordes and vastly over-publicized, they have retained their

quiet, unspoiled beauty.”

Bowderdale Beck

Looking down Bowderdale

Right: Looking up Bowderdale

There is nobility in the simplicity of Bowderdale.

What you see is definitely what you get: there are no

hidden secrets. And yet it is a marvellous valley, running

due north for 6km or so and forming the prototypical

U-shape that illustrates the effects of glaciation. There

are also fine examples of Holocene (that is, post-glacial)

fluvial erosion, with alluvial fans, terraces, meanders

and braided channels.

The effects of glaciation are widespread in Loyne. It has

been covered with ice several times and in the last glacial

period, ending about 10,000 years ago, all but the highest

tops were under ice.

Glaciation has two general effects: erosion and

deposition. The most apparent erosive effect is the

scouring of valleys (such as Bowderdale), deepening and

straightening them to form the characteristic U or parabolic

shape. When ice accumulates in the lee of valleys, it may

form bowl-shaped cirques with deep sides. Generally,

though, Loyne rocks are too soft to provide the more

spectacular glacial forms seen, for example, in the Scottish

Highlands.

Deposits are in the form of till or boulder clay, that is,

largish pebbles in clay dropped by the ice, and sands and

gravel left by the actions of glacial meltwater. Drumlins

– the rolling, hummocky hills formed from boulder clay

– are common in Loyne. Sometimes, the deposits at the

ends or sides of glaciers (terminal or lateral moraines)

form barriers sufficient to change watersheds. The most

intriguing deposits are erratics, which are rocks carried on

glaciers and left in an alien landscape.

The detailed effects of glaciation are difficult to

unravel, especially when they involve major changes such

as the breaking through of watersheds, the formation of

new flow directions as glaciers block one another, and the

sudden release of huge volumes of meltwater.

Bowderdale Beck runs uneventfully from the head of

Bowderdale, 2km from The Calf, to the small community

of Bowderdale and then to join the Lune. The region

provides a typical Howgills walking area, with its long,

open ridges and steep, grassy slopes, striped with sheep

tracks, falling to an enclosed valley, empty of manmade

objects apart from a few old sheepfolds. There is little

excitement to be found on the ridge tops: Yarlside has a

distinctive dome; Kensgriff a few crags; Randygill Top

a small cairn; otherwise, there are just gentle rises that

provide extensive views.

Walk 1: A Circuit of Bowderdale, including Green Bell

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Near Wath on the road south of the A685 (685050).

There are three obvious routes between Bowderdale Foot and the head of Bowderdale – the west ridge, the east ridge, and

the valley bottom. Higher mathematics shows that there are six loops possible.

The walk along the valley bottom should be experienced, but not on a first visit. Impressive though the symmetrical valley

is, it becomes claustrophobic after a while. There is only one view and only the odd sheepfold to break the monotony. The west

ridge, beginning with West Fell, is the better one, providing good views into Bowderdale and Langdale and, in the distance, an

evolving panorama of the hills of the Lakes and Dales.

So begin by setting off southwest, past Brow Foot, to Bowderdale Foot and then onto the footpath that leads to West Fell

and Hazelgill Knott. You will meet many sheep, a few ponies perhaps, and, only if you are really lucky (or unlucky, as the case

may be), one or two other walkers.

Continue 2km south of Hazelgill Knott and, as the path begins to swing right (heading for The Calf), leave it to turn east to

Hare Shaw and Bowderdale Head to the unnamed hill south of Yarlside. Head north over Yarlside, Kensgriff and Randygill Top,

with distant views of Cross Fell, Wild Boar Fell, Ingleborough and the Lakes skyline.

Continue to Green Bell, where you may locate the spring that is the source of the Lune, just below some ruins off the Green

Bell to Knoutberry path. As you wish, follow the fledgling Lune down or, better, the path over Stwarth, in both cases cutting

across to Weasdale and thence to Wath (just follow the OS map through gates and fields: there are few reassuring signposts).

The distances are long but walking is easy apart from on the slopes of Yarlside. Route finding may be a challenge on the

eastern ridge but the trig point on Green Bell is a reassuring presence.

Short walk variation: A short walk up Bowderdale is hardly possible without tackling its steep slopes, so instead head directly for

Green Bell. Walk through Gars to Weasdale and then up Stwarth to Green Bell. Then, from the source of the Lune, follow Dale

Gill to Dale Tongue and cut over to Weasdale and then back.

The Lune from Bowderdale Beck ...

Right: The Lune at Kelleth

Right: The Lune at Kelleth

The Lune runs due west, more due than it used to as

it was straightened to run alongside the A685 when

it was rebuilt on the line of the old Newbiggin-on-Lune

to Tebay railway after it closed in 1962. This seems an

unnecessarily brutal way to treat the young Lune, just as

it is making its way in the world.

Becks, such as Flakebridge Beck and Cotegill Beck,

continue to enter the Lune from the south but very little

water flows from the north. The old limestone quarries

and limekilns that are seen on the slopes between

Potlands and Kelleth hint at the reason for the dryness of

the northern slopes. Limekilns, which usually date from

the 18th or 19th century, were used to burn limestone to

make quicklime. This was then slaked with water and

used to reduce the acidity of pastures and also to lime-wash buildings. The limestone was tipped into the

kiln from the top onto a fire of coal or wood, and then

more coal and limestone layered on top. The open arch

provided air to keep the fire going.

The members of Kelleth Rigg’s herd of pedigree

Blonde d’Aquitaine cattle look lime-washed too. Kelleth

itself is a small village, recently enlarged by new building,

aligned along the now quiet road by-passed by the A685.

The Lune reaches the rather ornate Rayne Bridge, built

of red sandstone. Well, the parapet and wall are of red

sandstone – the bridge itself isn’t, as a side view from

the east reveals. The bridge was built in 1903 to replace

one that required an abrupt turn on the road. Soon after

Rayne Bridge, Langdale Beck joins the Lune.

Langdale Beck

Left: Langdale from West Fell

Left: Langdale from West Fell

Langdale Beck runs north from The Calf for 12km

through the deserted valley of Langdale to emerge

at the small village of Longdale, close by the Lune.

There is sometimes debate about which of Langdale

or Longdale has been misspelled but they are surely

different renditions of the northern vowel sound that we

have in auld lang syne. Anyway, the dale is undoubtedly

the langest in the Howgills.

The Calf is the focal point of the Howgills and from

it there are extensive views in all directions. To the south,

the Lune looks like a snail’s trail entering Morecambe

Bay, and circling around we see the Bowland Fells,

Ingleborough, Whernside, Pen-y-Ghent, Baugh Fell,

Wild Boar Fell, and Cross Fell. Most eyes, however, will

be drawn westwards in the attempt to identify the classic

Lakeland peaks, such as Crinkle Crags, Great Gable and

Blencathra. The Calf itself is hardly a peak, being merely

slightly higher than several nearby mounds. There is no

bird’s eye view into nearby valleys that the best peaks

provide.

The Calf has many ridges leading towards it but it is

closer to the southern point of the Howgills triangle than

it is to the northern side. To the south there is one main

ridge (from Winder by Arant Haw) but to the north there

are many long, complicated, interlocking ridges, all very

similar in appearance. Langdale Beck itself drains a vast

area, with several significant tributaries creating deep

gullies with ridges between them.

The apparently timeless appearance of the Howgills

is misleading. Pollen evidence indicates that a few

thousand years ago Langdale was wooded, with alder,

birch and hazel on the valley floor and oak and elm on the

slopes. The almost complete removal of the woodland,

probably following the introduction of sheep farming in

the 10th century, has led to greatly increased soil erosion

and gully development.

Right: A walker near the head of Langdale (to the left), heading for The Calf

Right: A walker near the head of Langdale (to the left), heading for The Calf

Walking around Langdale is deceptively easy.

Physically, there is little problem because the grass is

easy to walk on and the slopes are gentle. There are more

tracks than are marked on the map, thanks to the farmers’

quads rather than walkers or sheep. Most people will

opt to walk on the ridges but if you wish to sample a

Howgills valley then Langdale is the best, because the

middle section has a flat valley bottom that provides an

openness lacking in other valleys, such as Bowderdale,

and there is an interesting series of incoming gullies.

The main problem is one of navigation. This is an

area where you should heed the advice to know where

you are on the map at all times. Don’t walk for two

hours and then try to work it out because there are few

distinctive features to help you. Keep careful track of the

few features there are (sheepfolds, gullies, scree) and if

on the ridges identify the few distinguishable tops (Green

Bell and Middleton with trig points, Randygill Top) and

keep them in perspective as you move along. Above the

pastures, there is no sign of past human habitation or

exploitation, such as quarries, to serve as a guide.

Left: Langdale, near Langdale Knott, with fell ponies

Left: Langdale, near Langdale Knott, with fell ponies

It is my duty not to exaggerate the attractions of

walking in the Howgills. Given a choice between walking

in the Lakes or the Howgills, I would choose the former

nine times out of ten. But on that tenth occasion, I’d look

forward to wandering lonely less the crowd.

The ordinary walker will relish the scenery and

solitude but specialists such as geologists and botanists

will find more of interest, especially within the eroded

gullies and scree slopes that are rarely visited by human

or sheep.

Langdale Beck is formed by the merger of West,

Middle and East Grain below The Calf, with the

relatively distinctive top of Simon’s Seat (587m) to the

west. Near a picturesque packhorse bridge, Nevy Gill

and the combined waters of Churngill Beck and Uldale

Beck join Langdale Beck, which then continues through

wooded pastures that are not part of CRoW land.

Langdale Beck is a fair size by the time it reaches

Longdale, a village of one farm, one row of cottages, a

couple more buildings, and the old school house. Within

the last began the education of Thomas Barlow (1607-1691), who became Bishop of Lincoln. He is a candidate

model for the traditional folk song character, the Vicar of

Bray, who blithely adapted his religious beliefs to meet

the changing political needs of the day. This is surely

a calumny, for northerners are known for the stalwart

independence of their views.

To the west of Longdale is the growing village of

Gaisgill, on the Ellergill Beck tributary of the Lune.

New ‘luxury homes’ have been built on the site of an

old garage. Nearby are a number of slightly less new

residences, and beyond them New House, dated 1848,

and beyond that Barbara’s Cottage, with a defiant date

of 1648.

Langdale Beck almost doubles the size of the

infant Lune, which is next joined by the first significant

tributary from the north, Rais Beck.

Rais Beck

Right: Sunbiggin Tarn, with the northern Howgills beyond

Rais Beck drains the broad, tranquil pastures that

lie between Sunbiggin and the ridge of 300m hills

to the north of the Lune between Newbiggin-on-Lune

and Raisgill Hall. It is formed by becks that run west

from Sunbiggin Tarn and south from the small village

of Sunbiggin.

The area around Sunbiggin Tarn and the adjacent

Cow Dub Tarn is appreciated by ornithologists, botanists

and malacologists (that is, experts on molluscs) – and

also by leisurely picnickers watching the shadows

lengthen on the Howgills. Although Sunbiggin Tarn

forms only 6 hectares of open water, it is the largest for some

distance around and is therefore an oasis for many birds.

Breeding species include wigeon, teal, tufted duck,

gadwall, mallard, little grebe, sedge warbler, water rail,

lapwing, curlew, redshank and snipe. The large colony

of black-headed gulls for which the tarn was known has

recently moved away.

Left: The view across Sunbiggin Moor to the Howgills

The tarn lies within a limestone upland and is

surrounded by heath, acid grassland, swamps, and areas

of chalky mire. These soils support a rich variety of plant

life, including various sedges, rushes and mosses as well

as the marsh orchid and rare bird’s eye primrose.

And for those malacologists, there are two rare

snails: Vertigo geyeri is known at no other British site

and Catinella arenaria at only three others. So, there’s

something of interest underfoot here at least.

[Update: These two snails are not as rare as I thought.

They are both on the list of endangered species in Britain but they have, in fact, been

found at several sites - although nowhere else in Loyne, I believe.]

The outflow from Sunbiggin Tarn joins Rayseat Sike

to form Tarn Sike, which is a Cumbria Wildlife Trust

nature reserve. Rayseat Sike runs by a Neolithic barrow

that was excavated in 1875 by William Greenwell, who

was, amongst many other things, a canon at Durham

Cathedral. In his remarkable 98-year life he investigated

400 burial sites and provided thousands of artefacts for

the British Museum. He served as a magistrate until the

age of 85 when he gained notoriety for suggesting that

speeding motorcyclists should be shot.

I would expect Rayseat Long Cairn to rank highly

among Canon Greenwell’s 400. The barrow is 70m long

and has a number of chambers in which burnt human

remains were found. Archaeologists speculate that it

could be one of the oldest such relics in the region. It is an

evocative site, now isolated on a rather bleak moor.

Right: Raisbeck pinfold, near Pinfold Bridge

Tarn Sike runs into a large pond at Holme House,

where it seeps away – except after heavy rain, when

it continues to form Rais Beck proper at Slapestone

Bridge, joining with becks running from the quietly

rural hamlets of Sunbiggin and Raisbeck. The latter

has a notice board with a helpful OS map so old that

all colour has long disappeared. The roads have wide

grass verges, indicating their origin as drove roads, with

limestone walls and scattered Scots pine and ash.

Rais Beck gathers pace as it passes Fawcett Mill,

built in 1794 and now a holiday home. Five fields north

of the mill may seem unexceptional but they have been

designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest for their

very naturalness. The site is one of the few remaining

traditionally managed plant-rich hay meadows,

relatively unspoilt by modern agricultural practices. The

flora includes betony, orchid, burnet, primrose, cowslip

and fescue.

Below Fawcett Mill is Raisgill Hall, a place with a

long history. There is an ancient tumulus nearby but it is

not worth a visit unless you are a trained archaeologist.

Manorial courts, to regulate the use of the commons,

were held at Raisgill Hall until the 18th century. They

were then taken over by the court at Orton, not without

considerable animosity and legal wrangling about the

boundaries and use of Orton and Raisbeck Commons.

However, the present owners of the Hall do not wallow

in the past: they are leaders of an active local farming

cooperative, which has received support from Prince

Charles, no less.

On a bench overlooking the Lune at Raisgill Hall

Bridge is carved “Go softly by this riverside for when

you would depart you’ll find it’s ever winding tied

and knotted round your heart”, which, if there weren’t

five differences, I’d assume to be an unacknowledged

quotation from The Prairie by Rudyard Kipling. We

bear the sentiments in mind as we follow the Lune for

1.5km with Tebaygill Beck joining from the south and

then Chapel Beck from the north.

Chapel Beck

Left: Limestone pavement at Great Kinmond on Orton Fells

Left: Limestone pavement at Great Kinmond on Orton Fells

The Lune watershed north of the A685 is formed by

the Orton Fells, comprising Orton Scar, Great Asby

Scar and Little Asby Scar. These are examples of karst, a

kind of landscape that we will meet elsewhere in Loyne.

The Orton Fells provide the largest area of limestone

pavement in England outside the Yorkshire Dales. It is

unfortunately not as large as it was because of earlier

quarrying but the area is now protected by law.

[Update: The Orton Fells are now within the Yorkshire Dales,

after the 2016 changes to the National Park boundaries.]

The best undamaged pavements are found on Great

Asby Scar, to the north of Raisbeck and Sunbiggin, and

are now protected as a reserve by Natural England. The

folding and jointing of the pavements is particularly

notable. The exposure of the site and the effects of

over-grazing have left only a few stunted trees, such as

hawthorn and holly. Within the grikes further woody and

non-woody species flourish, especially various ferns and

herbs.

The dry surface of these limestone plateaus was no

doubt partly why it was a favoured area for human

habitation long ago, as shown by the many remains of

ancient earthworks on the Orton Fells. Castle Folds,

near the trig point on Knott, is an Iron Age site, with

the ruins of hut circles on a natural limestone platform.

Below Knott there’s an ancient 40m-diameter circle of

about thirty stones, of variable size, all but one of pink

granite.

The pink granite may be a surprise, below the

limestone scars, but the occasional pink boulder can be

seen perched on the limestone pavements and scattered

in fields. They are erratics, brought here from the Shap

Fells by glaciers. Prehistoric man is not alone in finding

a use for these intriguing boulders: some amusement can

be obtained in spotting them in barn walls, protecting

beck banks, ornamenting houses, and marking boundaries

(for example, Mitchell’s Stone, 1km north of Sunbiggin

Tarn).

Karst refers to any terrain with soluble bedrock where, as

a result, there is little or no surface drainage. It is named

after an area of Slovenia but there are many kinds of karst

in the world, depending on climate, location, type of

bedrock, and so on. In our case, the bedrock is limestone,

which is dissolved by the mildly acidic rainfall formed by

the absorption of carbon dioxide.

The rainwater dissolves fractures in the bedrock,

gradually enlarging them into deep fissures called grikes.

The limestone blocks between grikes are called clints. On

the surface, these limestone pavements look barren, as

little soil forms on the clints, but within the deep, sheltered

grikes specialised plant communities flourish.

Underground, the rainwater continues to erode the

limestone, until meeting an impermeable lower layer,

giving rise to several characteristic features, such as: caves

with stalactites and stalagmites; sinkholes, shakeholes,

swallowholes and potholes, through the collapse of bedrock

above a void; springs, as water emerges at an impermeable

layer; disappearing streams, through water flowing into a

pothole. Over time, as underground passages are adopted

and abandoned, complex and extensive cave systems may

develop, to be explored by potholers.

The headwaters of Chapel Beck run from Orton

Scar, which on maps from the 16th century was marked

as “Orton Beacon” or by a beacon symbol. The beacon

warned of marauding Caledonians. Today Beacon Hill

has a prominent monument erected in 1887 for Queen

Victoria’s golden jubilee.

The becks run by and through Orton, the largest

settlement so far, as shown by the fact that we find our

first public house. Orton was made a market town in the

13th century and the numerous converging roads, tracks

and paths indicate Orton’s importance in the old droving

days. This rural heritage is echoed in the Orton Market

that today wins prizes, such as National Farmers Market

of the Year 2005, for its emphasis on local produce.

Left: Rough Fell sheep

Left: Rough Fell sheep

In 2006 Orton hosted a “Festival of the Rough

Fell” to celebrate the ancient breed of Rough Fell sheep,

its history, and the crafts associated with Rough Fell

farming. The majority of Rough Fell sheep are found

on the Howgills and surrounding fells. As the name

indicates, the Rough Fell is hardy enough to live on the

poor upland grasses of exposed fells. It is a large sheep,

with a black and white face and curved horns, renowned

for its thick wool, which is used to make carpets and

mattresses, and high quality meat.

The festival marked a recovery from the foot and

mouth epidemic of 2001, which caused great problems

throughout Loyne and, in particular, reduced the number

of Rough Fell sheep from 18,000 to 10,000. As the fells

were closed, the epidemic threatened the traditional

methods of fell management, whereby every flock knows

its own territory or ‘heaf’, with each lamb learning it

from its mother.

The mingling of old and new typifies modern

Orton: from the stocks near the church to the chocolates

from the recently established industry. Likewise, among

the few modern dwellings are some fine old buildings.

Petty Hall has a door lintel dated 1604. Orton Hall, to

the south, was built in 1662 and was once the home of

Richard Burn (1709-1785), vicar of Orton and author of

texts on the law and local history.

Right: All Saints Church, Orton

The All Saints Church was built in the 13th century,

replacing earlier temporary structures, and has been

rebuilt several times since. Inside the church there is a

display of three old bells, the oldest of 1530, and a list

of vicars back to 1293. The early 16th century west tower

is the oldest remaining part and today is an eye-catching

off-white. After modern methods to seal the leaking

tower failed, it was decided to resort to the traditional

treatment of lime washing. So far, it has worked.

Chapel Beck gains its name as it runs south past

Chapel House, where there is a spring, Lady Well, which

was known for its health-giving properties. As Chapel

Beck approaches the Lune we may glance east up the

Lune valley towards Newbiggin-on-Lune and reflect on

the contrast between the hills to the north (Orton Fells)

and to the south (the Howgills).

The geology of Loyne has a major impact on the

appearance and activities of the region but it is not as

complicated as, for example, the Lake District’s geology.

In general, rocks are of three types: sedimentary (formed

by the settlement of debris), igneous (derived from

magma or lava that has solidified on the earth’s surface)

and metamorphic (rocks that have been altered by heat

and pressure). The bedrocks of Loyne are almost entirely

sedimentary, with the sediments having been laid down

in the following order (youngest on top, naturally):

• about 300m years ago: Carboniferous (Silesian)

– mainly millstone grit

• about 350m years ago: Carboniferous (Dinantian)

– mainly limestone

• about 400m years ago: Devonian

– mainly sandstone

• about 450m years ago: Silurian and Ordovician

– mainly slates and shales.

The Howgills (apart from

the northeast corner) have had all

layers eroded away to the Silurian

and Ordovician. Orton Fells have

been eroded to the Carboniferous

limestone. Clearly, if the Howgills

still had a Carboniferous limestone

layer it would be much higher than

Orton Fells. This implies a tilt or slip

(a fault) to raise the Howgills side,

which would have made it more

exposed and vulnerable to erosion.

The word ‘fault’ suggests a minor

matter but the slippage, spread over

millennia, would have been of a

kilometre or more (the 2005 Asian

tsunami is thought to have been

caused by a slippage of a few metres).

There are literally all sorts of twists

and turns – some sudden, some slow

(but over unimaginable timescales)

– to complicate this brief outline but

it may serve as a starting point for

understanding Loyne geology.

Walk 2: Orton, Orton Fells and Sunbiggin Tarn

Map: OL19 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: The centre of Orton (622082).

Head for the unmistakable All Saints Church and walk east past the vicarage to locate the path north to Broadfell (on the left

bank of the beck). Take this path and after 100m follow the sign left through the houses. Thereafter, the path is clear, beside the

beck and beyond its spring, and emerges at a disused quarry on the B6260.

Cross the cattle grid and walk east on the north side of the wall to the monument on Beacon Hill. Within the extensive

panorama of the northern Pennines and the Howgills, locate on the skyline, 1km southeast, the trig point on Knott to the left of

a tree. That is your next objective.

Follow the wall east to a gate near the corner and through the gate turn half-left to another gate, picking up the bridleway.

Keep the tree in view and when the bridleway turns south leave it to head between limestone crags towards the tree. From the

trig point, there’s an excellent view, with Castle Folds prominent nearby. (Unfortunately, Castle Folds cannot be visited without

climbing a wall: the stile that can be seen is over an adjacent wall. In any case, I would not recommend walking east over the

limestone, as the clints are fragile and the grikes are deep. If you do so, a gate in the wall east at 658094 might be welcome.)

From the trig point, walk west on grass between the limestone to regain the bridleway and enter Knott Lane. Turn left on

a clear path (part of the Coast-to-Coast route) just north of the stone circle. Continue east to Acres and then along the quiet lane

to Sunbiggin and Stony Head, after which the road becomes a track. Shortly after entering the CRoW moorland, the bridleway

forks. Take the left branch heading northeast, to reach the road north of Spear Pots (a small tarn now almost overgrown). Walk

south on the grassy roadside verge to Sunbiggin Tarn, with good views of the Howgills beyond.

Past the cattle grid, take the bridleway right to reach the branch you met earlier. Now return to Knott Lane. This is the only

significant retracing of steps in our 24 walks but the path is excellent, with good views in both directions, and much better than

walking on the limestone scars or on the nearby roads. Cross Knott Lane and continue west past Scarside, across fields to Street

Lane and on to Orton.

Short walk variation: The long walk is a figure of eight. So the obvious short walk is to do half of the eight. Follow the long walk

to Knott Lane and then, instead of turning east to Acres, turn west to Scarside and Orton.

The Lune from Chapel Beck ...

Immediately after Chapel Beck joins, the Lune passes

under Tebay Bridge, a sign that we are approaching

Tebay. The village is split in two by the A685: the original

part now called Old Tebay and the newer part Tebay. In

the early 19th century Old Tebay was a community of

about ten houses, with Tebay consisting of little more

than the 17th century Cross Keys Inn.

In one of those houses lived Mary Baines (1721-1811), who was alleged to be a witch and is said to still

haunt the Cross Keys Inn. She was feared for various

diabolical deeds, such as foretelling “fiery horseless

carriages” (that is, trains), but why she should be feared

for a forecast that did not come true before her death is

hard to see.

When the railways did arrive, they transformed

Tebay. With a station on the west coast main line, which

opened in 1846, and a junction to the line that ran through

Newbiggin-on-Lune to the east coast, Tebay was a key

part of the Loyne railway network. In addition, there

were many sidings for the engines that were used to

boost trains over the Shap summit. The village migrated

south to be closer to the rail-yards, with terraces for rail-workers and a Junction Hotel being built a kilometre

south. St James Church, with its distinctive round tower

and conical top, was built in 1880, paid for by the rail

company and workers.

At its peak, the Loyne railway network consisted of eight

lines, plus lines out of Loyne to places such as Carlisle,

Kirkby Stephen, Skipton, Preston, Morecambe and

Windermere:

Tebay – Lancaster (1846-)

Wennington – Lancaster (1849-1966)

Clapham – Wennington (1850-)

Newbiggin-on-Lune – Tebay (1861-1962)

Lowgill – Clapham (1861-1964)

Wennington – Carnforth (1867-)

Settle – Carlisle (1876-)

Lancaster – Glasson (1883-1930).

We will encounter these lines, derelict or alive, many

times on our journey and some general comments are in

order, not on the details that railway enthusiasts are fond of

but on the railways’ impact on Loyne.

The building of the railways brought welcome

employment but they generally harmed local industry.

This was almost entirely small-scale activity to meet local

needs, such as basket-making, pottery, quarrying and coal

mining. It became easier and cheaper to import coal from

where it was plentiful, and while new markets were opened

up for local products they could not compete in terms of

price or quality with the outputs from the rapidly-growing

industrial towns. Consequently there was an exodus from

the villages to those towns.

The railways affected local transport. It was much

cheaper to send beef by train than by hoof. Therefore,

the drove roads fell into disuse, along with the associated

activities en route. Otherwise, most country tracks, used on

foot or on horse, were not much affected until the advent

of the car.

Scenically, the railways have now merged into the

countryside and are fondly regarded. Derelict lines are often

unnoticeable, except for structures such as the Lowgill

Viaduct and Waterside Viaduct, which still impress us.

They must have been awesome in the 19th century.

Right: A Tebay terrace

Tebay’s image has not recovered from the reputation

it gained in those times, which is hard to do when guide-writers persist in repeating old opinions, such as this one,

from Clement Jones’s A Tour in Westmorland (1948):

“The traveller … is apt to think - and how rightly - of

Tebay as a grim and grimy railway junction blackened

with the smoke of many locomotives and consisting

mainly of the ugly dwellings of workmen employed on

the railway.”

Today things are different. The Newbiggin branch

line closed in 1962, Tebay station was demolished in

1970, and the Junction Hotel is no longer a hotel. The

terraces are painted in multi-coloured pastel shades and,

below the green hills on a sunny day, present a handsome,

if not pretty, sight. But Tebay cannot fully escape the

impact of its location in a traffic corridor. There is an

ever-present hum or roar, depending which way the

wind is blowing, from the motorway, broken frequently

by the rattle of the London-Glasgow expresses.

Beyond the motorway the Lune passes a mound that

when glimpsed by motorway drivers might be assumed

to be the remains of a slagheap. It is in reality what’s left

of the motte of a Norman motte and bailey castle, now

called Castle Howe. Such castles consisted of an artificial

mound (the motte), with a wooden or stone building on

top, and a larger enclosed yard (the bailey) containing

stables, workshops, kitchens and perhaps a chapel. The

earth from ditches around the motte and bailey was used

to create the motte.

Castle Howe is the first of ten such remains that we

will meet on our journey. The castles were built soon

after the Norman Conquest to provide security against

rebellious northerners. It seems that Loyne’s locals were

not as obstreperous as elsewhere because its castles were

at the smaller end of the scale of over five hundred such

castles built in England. Mottes are typically from 3m to

30m high, with Loyne’s being nearer the lower end of

the range. Also, there are no remains of stone buildings

on any of Loyne’s mottes, indicating that the more

vulnerable wood was considered adequate.

The Loyne castles were probably for the strategic

and administrative use of landlords rather than for

military garrisons. They were built overlooking river

valleys and close to fertile meadows. Castle Howe is

the closest to the river itself and has lost half its motte

to flood erosion. The motorway at least has swerved to

avoid it, if only just. By Castle Howe the Lune, flowing

west, meets Birk Beck, flowing east.

The Previous Chapter (The Introduction)

The Next Chapter (Shap Fells and Birkbeck Fells)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Left: The view north standing at the source of the Lune on Green Bell

Left: The view north standing at the source of the Lune on Green Bell

Right: The Lune at Kelleth

Right: The Lune at Kelleth

Left: Langdale from West Fell

Left: Langdale from West Fell

Right: A walker near the head of Langdale (to the left), heading for The Calf

Right: A walker near the head of Langdale (to the left), heading for The Calf

Left: Langdale, near Langdale Knott, with fell ponies

Left: Langdale, near Langdale Knott, with fell ponies

Left: Limestone pavement at Great Kinmond on Orton Fells

Left: Limestone pavement at Great Kinmond on Orton Fells

Left: Rough Fell sheep

Left: Rough Fell sheep