The Land of the Lune

Chapter 13: The Lune to Lancaster

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Lune Floodplain and the Top of Bowland)

The Next Chapter (The Salt Marshes)

The Lune Aqueduct

The Lune from Artle Beck ...

Right: Penny Bridge, Crook o’Lune

Right: Penny Bridge, Crook o’Lune

After 1km the Lune reaches the Crook o’Lune, a

popular picnic spot where the Lune meanders in

a graceful curve under wooded banks. There are

three bridges. The first and third, on opposite sides of

the meander, were for the Wennington-Lancaster railway

line. The second is Penny Bridge, which was built in

1883 after the 1806 bridge collapsed. This was a toll

bridge but rather than pay the toll some people preferred

to cross the Lune on foot, not always successfully.

In the summer the river banks and surrounding

fields provide a colourful display that would be regarded

as beautiful in other contexts. Here it should be viewed

with alarm, for the purple flowers are of Himalayan

balsam, an alien, fast-growing, invasive species that

swamps native plants, so that when it dies down in the

autumn it leaves the banks vulnerable to erosion. Its

nectar-rich flowers also attract bees away from native

species. It can be eradicated relatively easily but attempts

to do so must begin in the upper reaches of the Lune

and Rawthey where the balsam has become established,

because its explosive pods spread the seeds, which are

carried downstream in floods.

At the Crook o’Lune a small beck, Escow Beck,

slips into the Lune. This, with its tributary Deys Beck,

originates 2km south in Flodden Hill Wood. This name is

thought to be due to Richard Baines, who was given land

in the area by Lord Monteagle of Hornby in reward for

his bravery at the Battle of Flodden Field. He no doubt

gave his own name to Baines Cragg, which provides

a fine viewpoint over Lancaster and Morecambe Bay.

Escow Beck flows through the pond at Escowbeck

House, which John Greg, the then owner of Low Mill,

built in 1842. He had the grounds landscaped so that a

sight of what he owned did not spoil his view, and as a

result it is difficult for us now to see the house.

Above the Crook o’Lune is Gray’s Seat, a recently

restored viewpoint that was eulogised by the poet

Thomas Gray in 1769. He wrote that “every feature which

constitutes a perfect landscape of the extensive sort is

here not only boldly marked but in its best position”.

These words are carved at the viewpoint, beside a grand

seat made by the renowned woodcarver Jim Partridge.

Gray’s view seems intended to rival Ruskin’s View

at Kirkby Lonsdale, which, after all, it does pre-date.

It was well known in the 19th century, as the effusive

paraphrase of Gray’s words in A Pictorial History of the

County of Lancashire (1854) indicates: the view “leaves

nothing to be desired in a landscape that pleases rather

than surprises, and of which the prevailing character is

more beauty than grandeur … we see nothing misplaced,

and desire neither to add to nor take away [a] solitary

object.” Since then we have added eight wind turbines.

Today, trees largely obscure the view and it is surprising

that we are encouraged to dash across the dangerous

A683 to see what’s left of it. (Gray’s Seat is probably

not Gray’s view at all: he stood to the north of the road,

400m below the “more advantageous station”, according

to the 1821 editor of Gray’s Guide to the Lakes.)

Left: Near the Crook o’Lune

Left: Near the Crook o’Lune

As we sit with our cuppa at the Crook o’Lune picnic

tables, admiring the view (shown in the

Introduction) up the Lune valley to Ingleborough,

contemplating the words of Thomas

Gray, mulling over the wind turbines on

Caton Moor, and fretting over the banks

of Himalayan balsam, we may lapse into

a reverie on the nature of naturalness. In

2006 various agencies coalesced to form

Natural England, which on first hearing

seems a rather strange name for a public

organisation. Its brief is “to conserve

and enhance the natural environment”.

So, naturally, we are led to ask: “What is

natural?” and in particular “What of Loyne

is natural?”

The name of Himalayan balsam tells

us that it doesn’t belong here. Similarly, for

the more pernicious Japanese knotweed.

What about the rhododendron that has run

amok at Kitmere and many other places

in Loyne? It is a native of Southern Asia.

Should we seek to eradicate it? Is there

any enthusiasm for giant hogweed (from

Asia)? Its name alone suggests we can do

without it! What about all those alien plants

that Reginald Farrer brought to Clapham?

Should we demand the removal of the fine

araucaria that stands alone in a field near

the Roman milestone at Middleton? It is

not a native tree: is it a natural one?

Apart from introduced species, what

about all those plants, such as cowslip and

primrose, that used to be abundant but are

now rare or extinct? Are they, or should

they be, part of the natural environment?

So many of our lowland meadows have been taken

over for agricultural purposes that those that remain in

anything like a natural state (such as those at Raisbeck,

Bretherdale and Tatham) are so rare that have been made

Sites of Special Scientific Interest. And, as we have seen,

the grouse moors have to be carefully managed to retain

what we now consider to be their natural state.

What could be more natural than the Ingleborough

that we see in the distance? Well, we know that a century

ago it would in the autumn have looked purple from the

Crook o’Lune viewpoint. Its slopes were then heather-clad. Before that, they would have been tree-covered.

Even Aughton Woods in the middle distance are not

entirely natural. Within Loyne the Forestry Commission

plantations, usually of conifers, occupy a greater area

than the remaining broad-leaved woodland. But before

the trees, of course, it would all have been ice-covered -

which is, if you take the long-term view, our most natural

state over the last million years.

There are similar considerations when we come

to consider the naturalness of Loyne’s animal life.

The red squirrel and grey squirrel debate is a familiar

one. Similarly, the otter and mink. We are seeking to

encourage the return of the former and to eradicate the

latter. What about the polecat? One has been trapped and

others sighted in Loyne. Should it be welcomed?

On farmland, do we mind alpaca (from South

America)? They are assuredly not as natural as our sheep

- the majority of which are (from) Swaledale. Why did I

include a photograph of a black swan rather than a white

one? Are we actually rather fond of the exotic?

Do we object to the red-legged partridge moving

north into our area? It is a handsome bird. Is our opinion

influenced by the fact that it was introduced as a game

bird in the 18th century (it is also known as the French

partridge)? Or that the once common grey partridge is

now on the red list of endangered species? Is it natural

for gulls to nest on Bowland Fells? Or for oystercatchers

to travel far inland? Would we welcome the eagle owl,

which has recently returned to other parts of England?

Is it more natural here than the little owl, which was

introduced in the 19th century? What about the pheasant,

introduced from Asia so long ago that nobody is quite

sure when?

Of course, none of the man-made constructions that

we see are natural. It is always the most recent (today,

the wind turbines) that are the most controversial. But

we can also see the old railway line, Low Mill at Caton,

electricity pylons, the chimneys of Claughton brickworks,

the Thirlmere aqueduct, and Hornby Castle. The last is

not even a ‘natural’ castle, since it was re-built in the

19th century to pretend to be one. To varying degrees,

we now accept these as part of the environment.

On a smaller scale, there are innumerable instances

of our tinkering with the environment. For example,

the Lune banks have in many places been reinforced

to prevent erosion. Fair enough: farmers don’t want to

see their fields disappear. But why are huge limestone

blocks often used? Their white gleam does not belong

here. As I write, a bulldozer is pushing rocks and soil

over the natural bank opposite Aughton Woods, burying

sand martin nests and anything else that happens to be

there. Just upstream from the Crook o’Lune a single

electricity wire crosses the Lune. It is surrounded by

seven prominent ‘danger of death’ signs. Fishermen

surely do not need such protection.

Almost everything mentioned in this reverie

concerns changes since Thomas Gray considered the

landscape perfect in 1769. Was the environment natural

then, or now? So many questions, but no answers. I

suppose the answer is that we should all notice, question

and decide about what we wish to see and have in our

environment.

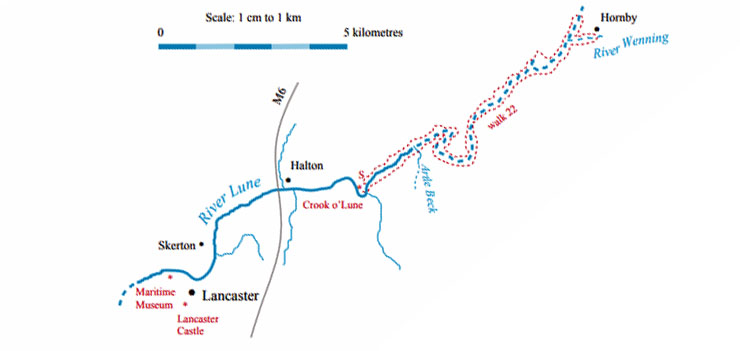

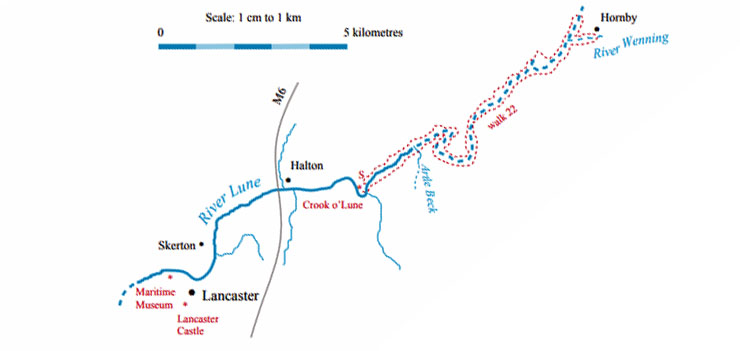

Walk 22: Crook o’Lune and Loyn Bridge

[Update: This walk is no longer possible because the bridge over Claughton Beck has

disappeared. A detour to Claughton and along the A683 is no fun at all. If you want a long walk

east from the Crook o'Lune it is better to stay on the north bank, continuing to Aughton or Eskrigge,

as you wish, and returning to the north through the Highfields. I have left the original walk

description here in case the bridge is restored (although, to be honest, I think I'd find

the walk too long and lacking in variety to recommend today).]

Map: OL41 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: The Crook o’Lune (522647).

Guidance for this suggested walk is simplicity itself: walk from the Crook o’Lune on the east side of the Lune to Loyn

Bridge and then back on the west side.

In a little more detail: Walk east over the old railway bridge and then immediately take the path right and then right again

to go under the bridge you’ve just crossed to gain the footpath on the east bank of the Lune. At the Waterworks Bridge continue

on the bank, as there is a good stretch of the Lune below Lawson’s Wood, where salmon often leap. Follow the long loop round

until you are again heading northeast. Don’t take the public footpath to Claughton but continue on the river bank where there is a

permissive footpath not marked on OS maps. This continues to the Wenning, where it is necessary to walk east to Hornby Bridge

and then back on the other side of the Wenning. Continue to Loyn Bridge where, if the footpath under the bridge is impassable

because the river is too high, you should cut up through the wood to reach the road. Walk over the bridge and take the path south

on the west bank of the Lune. As this is part of the Lune Valley Ramble there should be no difficulty in navigation. At the long

meander near Burton Wood nobody will object if, through exhaustion, you need to walk straight across.

The walk can alternatively be started from Loyn Bridge, which would have the advantage of enabling a half-way cuppa at

Woodies snack bar at the Crook o’Lune. Between the Crook o’Lune and Loyn Bridge there is only one way to cross the Lune - at

Waterworks Bridge (the footpaths marked on the OS map as crossing the Lune are not paths for feet).

Short walk variation: There are several short loop walks from the Crook o’Lune that may be combined in any way you wish:

northeast to Waterworks Bridge and back (5km); east over the old railway bridge, south on the south bank of the Lune and

back over the other bridge (1km); west over the bridge, along the south bank of the Lune to Halton Weir and back along the

Millennium Park (2km); west along the Millennium Park to the bridge at Denny Beck and back on the north bank of the Lune

through Halton Mills (4km).

Cuppa finished, let us move on. Beyond the meander,

the Lune curves west. Here, on a winter’s afternoon, is

a good place to spot the kingfisher, for in the absence of

other colours the setting sun makes its iridescent blue

and orange particularly vivid when seen from the south

bank. According to the Lune Waterways Bird Survey

there are at most half a dozen breeding pairs between

Lancaster and Kirkby Lonsdale, so their frequency here

seems surprising.

On the south bank, 100m before Forge Bank Weir,

is the Lune Intake, the first sign of any significant

management of the Lune. Up to this point the Lune

and its tributaries have run largely unrestrained from

their various fells. There used to be a millrace from

the weir to power Halton Mills, a substantial industrial

complex that survived for over two centuries, changing

when necessary between cotton, flax, leather, oilcloths

and coconut matting, until becoming derelict in the

1970s. A renovation of the site was begun in 2006 by

a company with the motto “property touches emotion”.

How true! The residents of Halton’s 1960s bungalows

angrily objected to the scores of self-contradictory “rural

townhouses”. The project has been left suspended,

unfinished, after the developers went into administration

in 2008.

[Update: The project was later revived and completed - and now

even more houses are being built in Halton.]

The management of the Lune is important to enable

proper use of water resources, to make flood predictions,

to assess the impact of discharges, and to support the use

of the Lune for recreation. There are four flow-measuring

stations on the Lune (at Lune’s Bridge, Tebay (3), Killington

New Bridge (6), Caton (17) and Halton (16)) and a further

four on the Conder, Hindburn, Rawthey and Wenning

tributaries. The figures in brackets show the median flows

in cubic metres per second. The Halton figure is lower than

the Caton one because of water extraction, particularly at

the Lune Intake.

Water is pumped from the Lune to help provide

Langthwaite Reservoir with Lancaster’s water supply and

also to be transferred to the River Wyre along a 13km

pipeline as part of Lancashire’s ‘conjunctive use scheme’.

The Wyre catchment is heavily exploited for industrial and

public water supply and may be supplemented from the

Lune, provided that its flow is high enough.

There are over a hundred licences for water abstraction

from the Lune and its tributaries and if all the allowed

water were taken the Lune would be ‘over licensed’, that

is, flows would fall below necessary levels. Thankfully,

the actual level of abstraction is lower than licensed and

has decreased recently because of changes in the region’s

industry.

The nature of the Lune catchment area makes

this monitoring important. Flows in the floodplain are

determined by rainfall on the fells, and these run-offs have

different characteristics. Rain in the Howgills runs quickly

off the hills but in the Dales water percolates into limestone

until it is saturated, giving rise to flash flood conditions.

The continued health of the Loyne riverside flora and

fauna depends upon maintaining the required conditions

of erosion and sedimentation, and this needs to be better

understood.

Between Forge Bank Weir and Lower Halton Weir

the Lune’s natural turbulence has been increased in order

to provide rapids for canoeists. Stone banks protrude into

the flow to create eddies and waves, suitable for novices

at the lower end and experts at the higher, especially

under spate conditions.

On the south bank the Lune Millennium Park

continues along the old railway line. Various artworks are

passed, of which the most striking is that of Giles Kent,

whose website says that he creates “in situ installations

that enhance and elaborate on the natural properties of

wood … [the work] compliments the natural landscape

by responding to lines and shapes found around each

particular site”. There are nine upside-down larch trunks

with roots aloft.

[Update: The upside-down trees were, to everyone's relief, removed in 2012,

being deemed dangerous through having rotted.]

The park reaches the old Halton railway station,

which looks different from all the others we’ve passed

because it was re-built in 1907 after a fire. By the station

there’s a temporary-looking bridge across the Lune that

has stood since 1913. The crossing here has a chequered

history. While the railway was being built there was no

bridge across the Lune here and workers were ferried

across from Halton. In 1849 eight of them died when

washed away in a flood. Today such an event would be a

national tragedy; then it seems to have been accepted as

a price to be paid. A new bridge was opened in December

1849: it wouldn’t do to have potential customers from

Halton washed away. This was swept away in 1869 and

replaced in the same year. This in turn was replaced in

1913 by using the remains of the old Greyhound Bridge

then being demolished in Lancaster. The bridge operated

as a toll bridge until the 1960s and since the railway line

closed in 1966 it has been a matter of contention who is

responsible for its upkeep.

The Lune at Halton

North of the Lune is the village of Halton, the

larger eastern part of which is mainly new housing for

commuters but the older part of which is rich in heritage.

This part is clustered around the small tributary of Cote

Beck, which enters the Lune unobtrusively 200m below

the bridge. Cote Beck arises south of Nether Kellet,

rather tentatively, as is usual in limestone country,

below the large quarries. It runs by the M6 and then past

Furnace Cottage, where Cote Beck used to be called

Foundry Beck.

Below Dale Wood, Cote Beck passes the site of

Halton’s motte and bailey castle, now marked by a

flagpole. The site is relatively small but the motte, rising

3m above the bailey, can be clearly seen (although the

present top is not original) and traces of the bailey are

visible despite recent ploughing. The site is on private

land.

Left: The Viking cross at St Wilfrid’s, Halton

Left: The Viking cross at St Wilfrid’s, Halton

On the other side of the beck is the church, dedicated

to St Wilfrid, a 7th century Archbishop of York. Maybe

there was a church here from that time, although the

earliest remains are 12th century Norman stones built into

the arch. As we have seen with other churches, the tower

was retained when the church was rebuilt (by Paley &

Austin again) in the 19th century.

A Roman altar was found in the churchyard in 1794

and is now in the Lancaster City Museum. It bears an

inscription to the god Mars from Sabinus and his unit of

boatmen, perhaps grateful for their safe passage up the

Lune from Lancaster. There is no other evidence of any

Roman settlement at Halton, although it is likely that

there was a camp on what became the site of the castle

and it is assumed that there was a Roman road on the

north bank of the Lune up to Whittington and over a ford

to Over Burrow. Still in the churchyard is a cross carved

with Christian symbols and a version of the Sigurd the

Volsung legend by Norse settlers who came to the region

in the 10th century. It is 3.5m high, mounted on three

steps, with the top parts having been rather inexpertly

reassembled.

Halton, then, was an important centre before

the Norman Conquest, when it was held, like many

places we’ve visited, by Earl Tostig. At the time of the

Domesday survey, Halton was regarded as the centre

of lower Lune, with twenty-two villages, including

Lancaster, considered to belong to the manor of Halton.

When Roger of Poitou took over, he preferred to make

Lancaster his centre and the importance

of Halton waned. The Royal Foresters,

responsible for managing the king’s

forests in Lancashire, had Halton for

their principal manor until the Gernet

inheritance passed to the Dacre family

in about 1290. The lords of the manor

in 1715, the Carus family, perhaps still

smarting from Halton’s subordination to

Lancaster, gave helpful information to

the Jacobite Army on its way to occupy

Lancaster. From the 18th century, the

manor house, Halton Hall, passed through

several hands, gradually being split up

and demolished. Only one 19th century

wing remains, the rest having gone by the

1930s, apart from the boathouse on the

Lune.

Right: The M6 bridge

Right: The M6 bridge

The Lune is slow, deep and wide,

and local rowing clubs make good use of

this section, down towards Skerton Weir.

Rowers get the best view of the fine M6

bridge, whose single-span arch of 70m

provides a frame for an attractive stretch

of the Lune.

In view of the on-going controversy

about a proposed link road from the M6

just north of the Lune to Heysham, it is

interesting that this was already part of

the original plan in the 1950s. It was only

when the Lancaster emergency services

expressed concern at the difficulties of

gaining access to the motorway that an

interchange south of the Lune was built,

to lower design standards than normal and

only later, after public representation, that it was opened

for general use.

[Update: This motorway junction was duly reconstructed during the 2010s,

with a new bridge being built over the Lune to link to the Bay Gateway to Morecambe and Heysham.]

After passing the Halton Training Camp for army

cadets on the north bank and a hotel and industrial

buildings on the south, the Lune reaches the Lune

Aqueduct, one of the finest aqueducts in England. It is

200m long, with five semi-circular arches carrying the

Lancaster Canal 18m above the Lune. It was one of

the first bridges designed by John Rennie, who went on

to design Waterloo Bridge and London Bridge, and was

a great civil engineering feat for its time. The aqueduct

was completed in 1797 and some indication of its impact

and aesthetic appeal can be gained from the fact that

Turner sketched it on his 1797 tour of northern England.

This was the only time on his tour that he addressed

a contemporary subject, although he could not resist

framing a view of Lancaster Castle within one of the

arches.

However, the grandeur of the aqueduct’s design was

not without its critics. A committee set up in 1819 to

review progress on the Lancaster Canal commented that

resources had been wasted in “ornamenting the town of

Lancaster, with a grand aqueduct over the Lune, upon

which the water had lain stagnant for over twenty years.”

It is not stagnant now: it is leaking. The aqueduct was

closed for repairs in 2009, as part of a £3m project to

develop the Lancaster Canal as a key part of the visitor

infrastructure.

After 1km the Lune reaches Skerton Weir, the

normal tidal limit. A weir has existed here for centuries,

to provide water for a millrace to power corn mills by

the Lune, but the present structure was built in 1979 to

prevent salt water entering intakes for the Lune-side

industries upstream. It does, of course, have a fish pass

for salmon and trout.

The weir is of disappointing design. It is unsightly;

it is not integrated into the so-called riverside parks

to provide an appealing leisure amenity; and it is a

hazard for river users, who are regularly swept over

it, sometimes with fatal consequences. The UK Rivers

guidebook describes the weir as “extremely dangerous”

and “lethal in high water”, rating the weir as grade 6

on the International Grading Scale, that is, the highest

possible (or most dangerous) grade.

In the past the weir was renowned for its salmon

fishing. Fishing is now regulated by the Environment

Agency, who own three beats on the Lune. Fishing directly

below the weir is prohibited but further downstream fly-fishing is allowed. Above the weir, coarse fishing with

a single rod is permitted, outside the close season, of

course. The Agency’s other two beats are upstream, at

Halton Lower Beat and Halton Top Beat. The former is a

game fishery, best fished at high water; the latter is slow,

deep water and is said to be the most productive of all

the Agency’s salmon fisheries.

Lancaster Canal was intended to connect Kendal with

Houghton, and hence the Leeds–Liverpool Canal, but has

yet to achieve that goal. The Act approving its construction

was passed in 1792 and the sections from Tewitfield to

Preston and from Walton Summit (6km south of Preston)

to Houghton were completed by 1803. The costs, however,

were high: for example, the bill for the Lune Aqueduct

(£48,000) was nearly three times the original estimate.

The Kendal to Tewitfield section took until 1819 but

no canal link between Preston and Walton Summit was

constructed – until 2003, when the Millennium Ribble Link

was finally built. But by this time the Kendal to Tewitfield

section, now cut off by the M6, had largely been filled in.

The grandly named Association for the Restoration of the

Lancaster Canal, formed in 1963 at the time of the M6-enforced separation, still hopes to re-open the Kendal to

Tewitfield section for navigation.

The Lancaster Canal is misnamed because, although

it was intended to help get goods to and from Lancaster

avoiding the Lune, the main beneficiaries were Preston and

Kendal and other villages en route. Preston, which had its

own problems with navigation in the Ribble, was in 1792

smaller than Lancaster but its population trebled in thirty

years as new markets opened up. The main effect within

Lancaster, which had lacked water-powered mills, was the

development of steam-powered mills alongside the canal,

where coal could be delivered easily.

The eight-hour journey from Kendal to Preston

could not compete with the railway when it arrived and

the Lancaster Canal Company was duly dissolved in 1886,

with the last freight being carried in 1947.

Today, the 66km from Tewitfield to Preston is for

leisure only. As it follows the contour there are no locks, to

the disappointment of today’s canal travellers, who seem to

revel in them. If that makes the canal too boring they could

try counting the bridges (Lancaster City Museum asserts

that there are 247 of them, including 22 aqueducts – which

I assume includes those bridges still standing, mysteriously,

in fields between Kendal and Tewitfield). Or they could

tackle the Ribble Link, which has nine locks in 6km.

The Lune flows through the built-up areas on the

outskirts of Lancaster and the becks, such as they are, run

unobtrusively through culverts to the river. For example,

Newton Beck joins on the east bank from the estates of

Ridge and Newton. On the west bank is Skerton, which

was mentioned as a separate village in the Domesday

Book and remained apart from Lancaster until the late

19th century.

Skerton Bridge was designed by Thomas Harrison,

who had studied in Italy, and is in a classical style

similar to that of the old Roman bridge at Rimini. Its flat

roadway and use of balustrades across the width were

innovatory for English bridges. There are five elliptical

arches, each spanning 20m. It was completed in 1788 and

soon influenced other designers. We might, for example,

detect an echo of Skerton Bridge in the Lune Aqueduct,

for John Rennie came to see it and a flat design was

exactly what was needed for the aqueduct.

A sixth, inferior arch was later added to Skerton

Bridge on the east bank for the Wennington-Lancaster

railway line. The station was just south of the bridge

at Green Ayre, which is today a rare example of an

industrial site that has been returned to a green field,

quiet apart from the skate-boarders’ ramp and the

traffic. The railway line continued from Green Ayre over

Greyhound Bridge to Poulton-le-Sands, or Morecambe

as it became called. The present Greyhound Bridge was

built in 1911, replacing earlier bridges of 1849 and 1864,

and converted for road traffic after the closure of the

railway line in 1966.

Green Ayre has had a long and active past. Some

experts believe that at the time of the Romans, Green

Ayre was an island, with the main flow of the Lune

being south of its present course, along the line of

the present Damside Street. A millrace followed this

line and powered what is believed to be the oldest

recorded water mill in Lancashire, being referred to in

the borough charter of 1193. Green Ayre then became

a busy quay and from 1763 a shipyard. It doesn’t seem

an ideal spot for such activities because the old bridge,

dating back to at least the 13th century, prevented large

ships from reaching Green Ayre. Newly built ships were

floated from the shipyard under the bridge in parts and

assembled downstream.

When Skerton Bridge was built the old bridge

became redundant. The shipyard bought the bridge

in 1800 and removed one arch, which reduced its

functionality somewhat but allowed tall ships to pass

through. By 1845 the whole bridge had fallen down or

been demolished.

Left: Greyhound Bridge and the Millennium Bridge below the castle and priory

Left: Greyhound Bridge and the Millennium Bridge below the castle and priory

The Millennium Bridge, opened in 2001 for

cyclists and pedestrians only, is roughly where the old

bridge stood. Opinions on this new bridge are mixed:

some people don’t like it much; others don’t like it at

all. Certainly, for cyclists and pedestrians it is a boon,

because for them Skerton Bridge and Greyhound Bridge

are inconvenient and dangerous. The bridge is a key part

of the Lune Millennium Park, linking the cycleways

along the old railway lines from Caton and Morecambe

to form part of National Cycle Network route 6. It was

designed by Whitby Bird, cost £1.8m, has a span of

64m and is suspended from 40m masts. Perhaps we will

eventually come to admire the classic view of Lancaster’s

castle and priory now framed by the long blue fingers

that are supposed to echo old sailing ships.

From Green Ayre, the castle and priory look as

one, overseeing the city of Lancaster, dominating the

strategically important lowest old fording point of the

Lune, and providing extensive views over Morecambe

Bay and up the Lune valley to Ingleborough. What is

now called Castle Hill was settled long before the castle

existed, with Neolithic and Bronze Age artefacts having

been found here.

The Romans recognised its key position overlooking

a main route between Scotland and western England. Of

the Roman fort that was based on Castle Hill there is little

to be seen but more than we saw at Low Borrowbridge

and Over Burrow. Most of the site is under the present

castle and priory but to the north in Vicarage Fields

the remains of a 2nd century bathhouse, excavated and

preserved in 1973, can be seen. The meagreness of the

remains does not excuse the shabbiness of the site and the

shamefully poor foreign language information board.

When Roger of Poitou moved his base from Halton

to Lancaster he no doubt built a motte and bailey castle

within the site of the old fort, although there is no trace

of this castle today. The Domesday Book records a

village called Loncastre here. The castle would have

been rebuilt in stone and strengthened part by part. The

12th century keep is the oldest surviving part. Scottish

raiders in 1322 and 1389 ruined much of Lancaster but

spared the castle and, to a lesser extent, the priory. During

the Civil War, Parliament ordered that the castle (apart

from the courts and gaol) be demolished but in 1663 the

king agreed to have it repaired. The gatehouse, the most

impressive external feature, is 15th century, with the John

of Gaunt statue added to it in 1822.

The name Loncastre may prompt some speculation on

the origin of the name ‘Lune’. Since the Domesday Book

the name has appeared in many forms (Lon, Loin, Loon,

Lonn, Lone, Lona, Loune, Loone, Loyne, Loine, Lan, and,

of course, Lune) but clearly it has pre-Norman origins.

There is not yet agreement on what the Romans called

their fort at Lancaster. The assignment of Alauna or Alone

is now discredited. Possibly it was the Calunio or Caluvio

of what’s called the Ravenna Cosmography. The Artle

Beck milestone’s “I L M P IIII” suggests that the name

began with ‘L’. It seems probable, then, that a Lune-like

name existed in Roman times.

So the origin is lost in pre-history and, in this case, we

may as well adopt a suggestion that appeals. Eilert Ekwall

concludes in English River Names (1928) that it comes

from the old Irish (and probably old British) slán, meaning

healthy, sound or safe, which is a fair enough description

of the Lune.

Right: Lancaster Castle gatehouse

Right: Lancaster Castle gatehouse

The grandeur of the long-distance view, with the

battlements on the skyline, is not sustained at close

quarters, where the bland, relatively modern, external

wall dominates. If you prefer a castle to be in dramatic

ruins redolent of historic battles then Lancaster Castle

is a disappointment: it is still in good enough repair to

continue as a working castle, functioning as court and

prison. Even so, it is arguably Lancashire’s greatest

historical building.

[Update: The castle ceased functioning as a court and prison in 2011.

It is now open to the public, after being refurbished with a piazza and café.]

Lancashire became a County Palatine in 1351,

with John of Gaunt becoming Duke of Lancaster, a title

that passed to his son, who became Henry IV in 1399.

Since that date the monarch has continued to be Duke

of Lancaster and has retained the Duchy and the castle

as a separate estate to those of the Crown. As county

town, Lancaster held the Assizes two or three times a

year. They were held in the Crown Court from 1176 until

1971, when a Royal Commission on Assizes, chaired

by Lord Beeching (a second, and less controversial,

Beeching Report), recommended changes. Until 1835

it had been the only Assize Court in Lancashire. The

regular influx of Lancastrian gentry helped to sustain

Lancaster’s relative importance and to preserve its status

as county town even after the Industrial Revolution.

According to H.V. Morton’s In Search of England

(1927), “It is remarkable that Lancashire, which

possesses Liverpool and Manchester, should own a

delicious, sleepy, old county town like Lancaster, and

this is itself symbolic of the fact that the great industrial

new-rich cities of northern England – vast and mighty

as they are – fall into perspective as mere black specks

against the mighty background of history and the great

green expanse of fine country which is the real North of

England.” Since then, the black specks of Liverpool and

Manchester have been evicted from Lancashire.

Over the centuries, many famous and infamous

trials have been held at the castle. In 1612 ten ‘Pendle

witches’ were sentenced to death. Between 1584 and

1646 seventeen Roman Catholic priests were executed.

From 1660, about 270 Quakers, including George Fox,

were imprisoned. Innumerable felons were sentenced to

death, to provide public spectacles that up to 1799 were

held on the moor east of Lancaster and between 1799

and 1865 at what is now called Hanging Corner, outside

the castle. Grammar school boys were given a half-day

off to learn the price of sin. This entertainment was more

frequent than elsewhere, as the Lancaster court passed

more death sentences than any other.

We do things differently nowadays, but less so than

we might think. In 1975 the Birmingham Six, accused of

the Birmingham pub-bombings, were tried in Lancaster,

which with its high security prison next to the court was

felt safest for Britain’s biggest mass-murder trial. They

were sentenced to life imprisonment mainly on the basis

of confessions that were extracted under conditions that

“if the defendants’ stories were to be believed [implied

that] many police officers had behaved in a manner that

recalled the Star Chamber, the rack and the thumbscrews

of four or five hundred years ago”, as the judge said in

his summing up. They had – and the convictions were

eventually overturned in 1991.

The Shire Hall and Crown Court, which were

designed by Thomas Harrison and completed in 1798,

may be seen, along with Hanging Corner, in a tour of the

castle. In the Shire Hall are the heraldic shields of all High

Sheriffs of Lancashire since 1129. The High Sheriffs

are appointed annually and the ceremony of Shield

Hanging is deemed so important that it necessitated an

adjournment of the Birmingham Six trial. Within the

castle, the tour includes the ancient keep, the dungeons

and the medieval Hadrian’s Tower and Well Tower (or

Witches’ Tower).

The Top 10 historical sites in Loyne

By ‘historical’ I mean anything over a hundred years old:

1. Lancaster Castle

2. Norber erratics, near Austwick

3. Brigflatts, near Sedbergh

4. Castle Stede, Hornby

5. Middleton Hall

6. Sedgwick Trail, Garsdale

7. Leck Fell ancient mounds

8. Rayseat Long Cairn, near Sunbiggin

9. Claughton brickworks

10. Low Borrowbridge

Next to the castle stands Lancaster Priory. At

least, that is what everyone calls it although there has

not been a prior here since 1430. The church is said to

date from 630, or earlier. There is a Saxon doorway in

the west wall of the nave. The priory was founded in

the 11th century and Roger of Poitou promptly gave it

to the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Martin of Seez in

Normandy. This arrangement, whereby income was sent

to France, was strained by our war-like relationship with

that country and duly ended in 1414 when Henry V gave

the priory to the Convent of Syon in Middlesex. The

priory then became the parish church of Lancaster and

with the Dissolution of the Monasteries came under the

see of Chester.

Unlike most other churches we have met, the

tower (of the 18th century) is newer than the rest, which

mainly dates from a 15th century restoration. In external

appearance it retains the graceful serenity that we like

to imagine for that period. Internally, there have been

changes but not to the most outstanding feature, the

carved choir stalls of about 1340, which some people

consider the finest in England.

Despite its long history, Lancaster has few buildings

older than 1750, other than the castle and priory. Most

of its fine stone buildings in the Georgian style date

from the 18th and 19th century. Usually unnoticed,

perhaps because they are understandably not near the

city centre, are some impressive buildings that possibly

result from Lancaster’s role as county town. The Royal

Albert Asylum for “idiots and imbeciles of the seven

northern counties” was built in 1870, its opening being

declared a public holiday, suggesting that it was a matter

of civic pride. It closed as a hospital in 1996 and is now

the Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College, catering for over

four hundred girls from across the world. The Ripley

Orphanage was built in 1864 and is now a school and the

1816 County Lunatic Asylum at Lancaster Moor, which

cared for three thousand people, has been converted into

residences, with the 1883 annexe currently up

for sale.

[Update: The annex has now also been converted into residences.]

Right: The Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College (née the Royal Albert)

Right: The Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College (née the Royal Albert)

The Lune passes the most visible

indication of Lancaster’s period of prosperity,

St George’s Quay, built to inspire the ‘golden

age’ of Lancaster’s shipping trade, from

1750 to 1800. An Act was passed in 1749 “for

improving the navigation of the River Loyne,

otherwise called Lune, and for building a Quay

or Wharf, etc.” This was in spite of, or because

of, the difficulties that the port faced. Daniel

Defoe wrote in about 1730 that Lancaster

had “little to recommend it but a decayed

castle and a more decayed port” and Samuel

Simpson considered in 1746 that “the port is

so choaked up with sand, that it is incapable of

receiving ships of any considerable burden, and

consequently trade finds little encouragement

here.”

Left: The Judges’ Lodgings

Left: The Judges’ Lodgings

St George’s Quay was duly built by 1755,

with merchants buying blocks of land behind

the new quay wall to build warehouses. The

Custom House, for the payment of harbour

dues, was built in 1764 with graceful Ionic

columns, to the design of Richard Gillow,

who had a particular interest in the success of

the quay because his company (founded by

his father, Robert) depended on the import of

mahogany from the West Indies. The Gillow

company became world famous for the quality

of its furniture, still widely admired today.

Samples of its work can be seen in the Lancaster

Town Hall and in the Gillow Museum, which

is housed in the Judges’ Lodgings, Lancaster’s

finest town house. Later, Gillows fitted out

royal yachts but, after merging with S.J. Waring

in 1903, the company closed in 1961.

Today, most of the warehouses have been

converted into flats. The Custom House ceased

functioning in 1882 and passed through various

roles, including that of theatre, before finding

an eminently suitable one as the Maritime

Museum in 1985. The museum provides an

excellent picture of the lower Lune, including

the port, the canal and Morecambe Bay.

While we are on an aquatic theme, I’ll

mention the zenith of Loyne’s sporting prowess.

The region has no major sporting venues or

events but in the suitably unsung sport of water polo

Lancaster won the British Championship every year

from 2003 to 2009, with the exception of 2008.

The Lune passes under its 43rd and last bridge,

Carlisle Bridge, for the west coast main line. Its

construction in 1846 conceded defeat for St George’s

Quay, because larger ships could no longer reach it.

The 1848 OS map marks Scale Ford 0.5km below the

bridge, indicating that the Lune here was much too

shallow for large boats anyway. In fact, in 1826 the new

steam ship John o’Gaunt had run aground here, much

to the disappointment (or amusement) of the assembled

spectators. The Port Commission did not give up

entirely: it used the compensation received from the

railway company to develop New Quay downriver of

the bridge.

Lancaster’s shipping trade, in terms of ships arriving

from or leaving for foreign ports, peaked in 1800 at 78

ships. It is a common, but mistaken, belief that Lancaster

was once a much bigger port than Liverpool and that it was

the rapid growth of the latter that ended Lancaster’s trade.

The figures show that both Lancaster and Liverpool were

minor ports in the early 17th century, with Lancaster being

the smaller, and that Lancaster grew slowly through the

18th century as Liverpool grew faster.

The main trade was with the West Indies, importing

sugar, rum, mahogany and cotton and exporting hardware

and woollen goods. Lancaster was the fourth largest port

for the West Indies trade, with about 8% of the outward

and 5% of the inward trade. The disparity in the two figures

results from Lancaster taking less part in the triangular slave

trade (whereby ships travelled to Africa, then America and

back to England) than other ports. The register shows that

the highest number of ships travelling from Lancaster to

Africa in any one year was 6 in 1772 (Liverpool registered

107 such ships in 1771).

There was also considerable European trade, such

as the import of timber from the Baltic, and much local

shipping: in 1800, 273 ships registered for trade within

Britain. After 1800, wars at sea harmed foreign trade

generally and continued silting harmed the port of Lancaster

in particular. Several local banks failed and merchants

took their trade to Liverpool and elsewhere. Although the

numbers of ships continued to rise until 1845, reaching a

peak of 712, very few of these were from overseas and

Lancaster’s proportion of the increased national trade was

much reduced. The quay was transferred from the Port

Commission to Lancaster Corporation in 1901.

The Top 10 cultural sites in Loyne

1. Maritime Museum, Lancaster

2. Lancaster City Museum

3. Ruskin Library, Lancaster University

4. Farfield Mill, Sedbergh

5. Storey Gallery, Lancaster

6. Judges’ Lodgings, Lancaster

7. Dent Village Heritage Centre

8. Cottage Museum, Lancaster

9. Bentham Pottery

10. Finestra Gallery, Kirkby Lonsdale

The Lune Shipbuilding Company was established

beside New Quay in 1863, aiming to build iron clippers.

Its first ship, the Wennington (the company chairman

lived at Wennington Hall), took three sets of emigrants

to New Zealand before disappearing in the Bali Straits

in 1878. The Lune Shipbuilding Company had already

disappeared by then, having gone bust in 1870, after

building just fourteen ships.

The site was then bought to extend St George’s

Works, a factory built from 1854. By the 1890s this

was said to be the biggest factory in the world owned

by a single man. There is no way of verifying this

now (although it seems unlikely) but the factory was

certainly large enough to employ a quarter of Lancaster’s

workforce. The ‘single man’ was James Williamson the

younger. His father, also James, had invented a type of

oilcloth as a table baize and set up the company, which

the son took over in 1875 and developed to manufacture

linoleum, in particular. He eventually became Lord

Ashton – the Lord Linoleum of Philip Gooderson’s 1995

book, Lord Linoleum: Lord Ashton, Lancaster and the

Rise of the British Oilcloth and Linoleum Industry.

In 2004 a £10m project for the Lancaster Economic

Development Zone was launched to revitalise ‘Luneside

East’. The industrial eyesore is being cleared and sold

to developers to build a “high quality, mixed-use urban

neighbourhood” by 2009, it was originally hoped.

However, in June 2008 the firm that had planned to

build 327 homes withdrew as a result of the housing

market downturn. In preparation, a 3km-long flood

defence has been installed, designed to protect lower

Lancaster against all except 1-in-500-year floods. It is a

bold person who will predict the effect of climate change

on sea levels in 500 years time.

[Update: Luneside East has since been redeveloped with

new houses but I don't know if this has followed the 2004 plan.]

The Priory and Custom House across the Lune

(the view after the trees were removed and before a 1.4m high flood defence barrier was installed)

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Lune Floodplain and the Top of Bowland)

The Next Chapter (The Salt Marshes)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: Penny Bridge, Crook o’Lune

Right: Penny Bridge, Crook o’Lune

Left: Near the Crook o’Lune

Left: Near the Crook o’Lune

Left: The Viking cross at St Wilfrid’s, Halton

Left: The Viking cross at St Wilfrid’s, Halton

Right: The M6 bridge

Right: The M6 bridge

Left: Greyhound Bridge and the Millennium Bridge below the castle and priory

Left: Greyhound Bridge and the Millennium Bridge below the castle and priory

Right: Lancaster Castle gatehouse

Right: Lancaster Castle gatehouse

Right: The Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College (née the Royal Albert)

Right: The Jamea Al Kauthar Islamic College (née the Royal Albert)

Left: The Judges’ Lodgings

Left: The Judges’ Lodgings