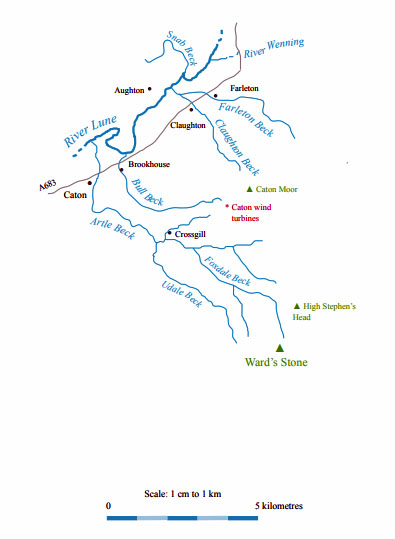

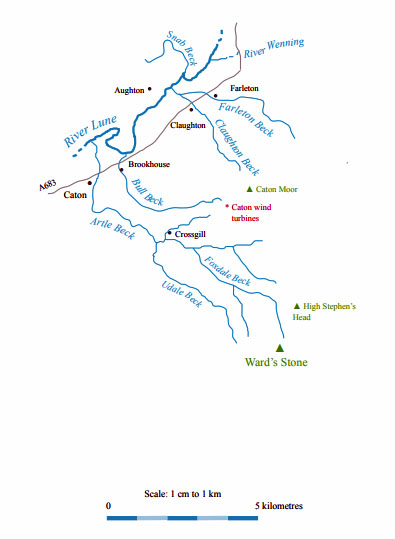

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 12: The Lune Floodplain and the Top of Bowland

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Wenningdale, Hindburndale and Roeburndale)

The Next Chapter (The Lune to Lancaster)

The Lune at Lawson’s Wood

The Lune from the Wenning ...

Right: The Wenning joins the Lune

Right: The Wenning joins the Lune

The augmented Lune flows in the middle of

its floodplain and there is naturally a sense of

remoteness, with wide views back to Hornby and

across to Claughton Moor. Birds of the river congregate

here and noisily object to being disturbed. In early spring

hundreds of curlew gather on the flat fields on their way

upriver to their breeding grounds.

There are footpaths on both banks of the river,

although walkers are rare in the middle section. On the

east bank, a permissive path from Hornby eventually

joins the public footpath below Claughton and on the

west bank the Lune Valley Ramble continues. The

Ramble cuts across from the Lune to The Snab, leaving

a long sweep of the Lune to the birdlife. The ponds that

have formed here are well used by swan, coot, moorhen

and heron. Above The Snab, on the footpath to Eskrigge,

there are good views across to Hornby, with Ingleborough

behind, and it’s also possible to see the flat green centre

of the ancient moat near Camp House.

[Update: There is no longer a bridge across

Claughton Beck - and I'm not sure if the permissive path still exists.]

Snab Beck makes its way to the Lune, running from

Higher Snab through a deep, wooded gully. The beck

used to be a fast-flowing tributary of the Lune until its

banks were silted up from the trampling of cattle and

sheep. The Lune Rivers Trust has tried to restore the beck

to its former state in the hope of attracting back wildlife

that has been lost, such as otter and water vole. Otters

are regularly recorded within Loyne but not so regularly

that the event is not thought worth recording. They have been

seen between Arkholme and Caton quite often and also

upriver at Tebay and Sedbergh and on the Wenning and

Roeburn tributaries. Water voles are thought to have

declined by over 90% since 1960 because of loss of

habitat and predation by the American mink that has

escaped from fur farms. The water vole was given full

legal protection in 2008.

Snab Beck now runs below the footpath and then

out to a large isolated pond, before following a route

west back to the Lune, which is soon joined on the

opposite bank by the combined forces of Farleton Beck

and Claughton Beck.

Farleton Beck and Claughton Beck

Farleton Beck and Claughton Beck are usually small

and sluggish but it is not always so. In 1967, on

the day of the Wray flood, similar but not so extensive

damage was caused in the villages of Farleton and

Claughton, through which the becks flow. The level

of the flood is marked on the wall inside the Fenwick

Arms.

Farleton is a cul-de-sac of mainly new houses lined

up around the old farms of Bank House and Brades.

Farleton’s only claim to fame is that in 1920 the owner

of the garage that used to exist next to the Old Toll

House was the first to paint white lines on a road, in

order to help motorists negotiate the dangerous corner.

This fact is so often repeated that it has become a self-evident truth. However, it is my sad duty to report that

many websites assert that Edward Hines, traffic engineer

of Detroit, used white lines in 1912. Ah well, it wasn’t

such a glorious claim to fame, anyway.

Left: The clay pit of Claughton brickworks

Left: The clay pit of Claughton brickworks

Right: The Claughton ropeway

Claughton Beck arises on Claughton Moor and runs

through the clay pit of Claughton brickworks, now owned

by Hanson Brick Ltd. This industry has survived, against

the odds, since the late 19th century. One of the aerial

ropeways installed in about 1900 is still used to bring

down the clay and shale from the moor and is thought to

be the last such ropeway still in use in England. The view

into the pit, with the buckets swinging overhead, is a

glimpse of a bygone industrial age. The pit, incidentally,

is not as large as might be imagined for a century’s

worth of bricks but for those concerned that the whole

of Claughton Moor might eventually be carried away in

these buckets it is reassuring that planning permission

for mineral extraction ends in 2018. The pit is due to be

returned to a natural state by 2020. Actually, quarrying to

the south and west of the pit has already ended, as rock,

rather than shale, has been reached but enough shale to

last about forty years lies to the east of the present pit. No

doubt, an application to extend the present permission

will be made in due course.

[Update: Yes, the permission was extended.

It now runs to 2036. I am now doubtful that one of the present ropeways was

installed in about 1900. At that time, the present clay pit did not exist.

Clay then was taken from lower down the hill. After a dormant period, because of

the financial crisis of 2008, the pit and ropeway were refurbished during the 2010s.]

Halfway down the hill, Claughton Beck runs

behind Claughton Hall, which has a magnificent view

of Ingleborough and the Howgills. The hall, parts of

which are said to be of the 13th century, looks grim and

austere, with its front always in the shade. It is hard to

get a close view of the hall because it is surrounded by

fences, plantations and the bank of a large, new pond.

There are two unequally large, stern towers, with oddly

placed small windows and uneven roofs, and tall, narrow

chimneys. It is difficult to believe that in the 1930s this

hall was moved stone-by-stone from its position in

Claughton and rebuilt to the original plan here, without

the opportunity for more substantial change being taken.

Perhaps the labourers reflected upon this while, as they

hauled the stones up, the clay for new bricks was passing

down over their heads.

Claughton Hall is owned by the Oyston family,

which may explain its increasing reclusion. Owen

Oyston, a media tycoon, was jailed for six years in 1996

after being controversially convicted of rape. After a

groundbreaking legal battle to establish that it wasn’t

necessary to admit guilt first, he was released on parole in

1999. But his trademark sheepskin coat and large fedora

have gone, and no longer do the bison roam extrovertly

in the field in front of the hall as they used to.

Claughton Hall Farm, an old building of character,

was left where it was, next to St Chad’s Church, a

medieval church re-built in 1815. One of the two bells is

dated 1296, making it the oldest dated bell in England.

As with Farleton’s claim to fame, I am afraid that I have

to pour some cold water. In 2002 St Chad’s was declared

redundant and permission granted for it to be converted to

residential use. In 2005 there was a planning application

to remove the bells so that they may be displayed in

St Margaret’s Church, Hornby, although in 2009 they

seemed to be still with St Chad’s.

The Lune from Farleton Beck and Claughton Beck ...

Sunset over a Lune-side lagoon

The Lune Valley Ramble passes Afton Barn

Cottage, which is a kind attempt to help us with

the pronunciation of the village above it, Aughton. I’m

tempted to suggest an extra f is needed but it depends

on how you say “good afternoon”. Although most of

Aughton’s buildings have been adapted for Lancaster

commuters, one or two barns managed to survive until

the present ban on conversion came into force. The

houses are arranged around a triangle, mainly on the two

quiet sides (not that the third side is busy).

The village stirs itself every 21 years for the

Aughton Pudding Festival, at which the ‘world’s largest

pudding’ is prepared. In the 18th century, Aughton, like

other Lune villages, made baskets from osiers, which

were made more supple by boiling. In 1782 someone

had the bright idea to use the osier-boiler to make a large

pudding, which became a tradition, which then lapsed

and was revived in 1971. On the last occasion a concrete

mixer was used. Why 21 years? I suppose it takes that

long to forget what a jolly silly idea it is. (It is said to be

because they used to cut the willow beds down every 21

years but does that require a large pudding?) Note it in

your diary: the next great pudding is due in 2013.

[Update: The 2013 Pudding Festival did happen, but with

relatively little fanfare. Perhaps it will lapse in 2034?]

Above Aughton, at appropriately named Whinney

Hill, is the Thoroughbred Rehabilitation Centre, opened

by Princess Anne in 2007. This transferred here from

Nateby, near Preston, and is said to be Europe’s first

charity dedicated to the welfare of ex-racehorses.

Aughton Woods line the steep northern slopes

above the floodplain. These woodlands have probably

never been cleared and include many species, such

as birch, oak, elm, ash and, notably, the small-leaved

lime. The woods, however, are not entirely natural, as

there are remains of about thirty charcoal hearths and

much sycamore, an alien tree, has had to be removed.

The Wildlife Trust manages parts of the area, some of

which are County Biological Heritage Sites. There are

permissive footpaths in Burton Wood and Lawson’s

Wood, allowing extensive banks of bluebells to be

viewed in spring.

Bluebells in Burton Wood

Opposite Burton Wood the Lune turns on a huge

meander. The lines of the parish boundaries and the

public footpaths show that the course of the Lune has

changed here. For some years the owner of the land on

the south bank, eroded by the Lune, insisted that walkers

must follow the official line of the footpath, that is, into

the middle of the Lune. Happily, a permissive path on

the bank was eventually agreed.

At the furthest point of the meander the Lune runs

by the dismantled Wennington-Lancaster railway line,

which at this point forms the beginning (or end) of the

River Lune Millennium Park, a leisure area leading to

Salt Ayre in Lancaster. Here also Bull Beck joins the

Lune.

Bull Beck

Right: The wind turbines on Caton Moor

Right: The wind turbines on Caton Moor

Bull Beck rises as Tarn Brook – a name whose

significance you may ponder for a minute – in the

shadow of the Caton wind turbines and near the spoil

heaps of the disused Claughton Quarries. The new picnic

site at the top of Quarry Road provides a fine view over

the Lune valley to the Lakeland hills, accompanied by

the hum, or more often the squeal, of the wind turbines.

Tarn Brook runs through a narrow wooded valley in

a region of old farmsteads such as Annas Ghyll and

Moorside Farm. The substantial Moorgarth was built in

the 1820s as a workhouse for 150 paupers from parishes

within about 15km. It was closed after an inspection in

1866 found it “wholly unsuitable” for the care of the

poor and later, in 1902, it was converted into a residence

for the architect Harry Paley, son of the Paley of Paley

& Austin.

Tarn Brook becomes Bull Beck in honour of the

Black Bull, the 16th century (or older) public house in

the village of Brookhouse, a name that underlines the

significance of Tarn Brook. Yes, it is the first ‘brook’,

rather than ‘beck’, that we have met, a transition in

nomenclature that is complete about 20km further

south. This is not just a terminological curiosity but

also an indication of the scope of Viking influence,

consistent with the disappearance of ‘fell’, ‘force’

(waterfall), ‘garth’ (yard), ‘gill’ (ravine), ‘keld’ (spring),

and ‘thwaite’ (meadow) across the Forest of Bowland.

Indeed, the name of Bowland is probably derived from

the Norse ‘bu’ for cattle rather than from the bow and

arrow.

Modern housing for Lancaster commuters has now

engulfed the old core of Brookhouse. There are three

halls within tottering distance of the Black Bull: the

Hall, the Old Hall, and Old Hall Farm. The Old Hall

was probably the ancient manor for the Caton estate,

although the present building is of the 17th century. The

church of St Paul’s, where there has been a church since

at least the 12th century, has helpfully retained something

of its past in both major re-buildings. The 1537 re-building retained the 12th century arched doorway in the

west wall, although it has been incongruously filled with

a jumble of oddments, some of antiquity. In 1865 the

church was again re-built (by the ubiquitous Paley) but

this time retaining the 1537 tower.

Bull Beck continues past the A683 picnic site, which

is a meeting point for bikers, to join the Lune.

The Caton wind turbines were the first modern windmills

to be constructed in Loyne – and the second. Elsewhere

in the Lune valley, wind turbine proposals have led to

heated debates and campaigning in STILE, that is, in

‘Stop Turbines In the Lunesdale Environment’, seemingly

oblivious of the fact that they are already here. Perhaps the

second set of wind turbines, twice as high as the first, are

more difficult to not notice.

Ten wind turbines were erected in 1994, even

though the site is within the Forest of Bowland Area of

Outstanding Natural Beauty. Its closeness to the pit being

gouged out by Claughton brickworks made it hard to argue

that the area was so outstanding that it must not be spoiled.

These turbines had a maximum capacity of 3MW, enough

to power about 1,700 households.

In 2006 they were replaced by eight turbines, yielding

16MW. Actually, with these turbines occupying four times

the area, the yield per ‘cubic metre of wind’ is less. The

turbines are now visible from all directions (including from

much of Loyne and indeed from areas of the Lakes and

Dales) and not just from the north and west. A proposal

in 2009 for a further twenty turbines across the moor was

entirely predictable (indeed, was predicted in the first

edition of this book). These turbines were proposed for the

area above the Claughton brickworks. However, showing

a newly-discovered appreciation of the virtues of (the

remainder of) Caton Moor, the proposal was rejected in

2010 by Lancaster City Council.

The aesthetic appeal of wind turbines is much debated

but generally with the long-distance view in mind. What

about the aesthetics on the spot? A position on Caton Moor

above Moorcock Hall gives the finest view there is of

the middle stretches of the Lune, with the Lakeland hills

behind. It also provides the longest possible view of the

Lune valley, from the Lune Gorge to the estuary – but now

the latter must be viewed through the blades of the wind

turbines.

The Lune from Bull Beck ...

Right: An alien black swan joins the Lune avifauna

Right: An alien black swan joins the Lune avifauna

The steep banks of the Lune are pitted with holes.

These are nests excavated by sand martins, which

arrive back in England in April and can be seen in large

numbers swirling and swooping over the river seeking

flies before returning to their nest.

Below Bull Beck is the lowest ford of the Lune still

in regular use. It is a little disconcerting to see tractors

setting off into a river that seems too deep but they head

boldly diagonally across to reach the farmer’s land

within the great meander.

The Lune continues its long curve to face whence

it came and then turns sharply under Lawson’s Wood to

head towards a bridge painted grey, with red roses. On

the side it says “Manchester Corporation Water Works

1892”. Within the bridge is an aqueduct carrying up to

250 million litres of water every day from Thirlmere to

Manchester. The Victorian style contrasts with the 1950s

austerity of the Haweswater Aqueduct passed near

Kirkby Lonsdale. The two aqueducts are now part of a

more complex system, collecting water from Ullswater

and Windermere as well, being joined near Shap, and

providing water to Liverpool, Blackpool and Lancaster

as well as Manchester.

The Thirlmere Aqueduct is 150km long, the longest

in England to work by gravity alone. As can be seen, the

four pipes across the bridge drop several metres to be

taken underground on the south side of the Lune. This is

the sharpest drop along the whole length of the aqueduct

(the average drop is just 30cm/km, and the water flows

at 6km/hour) and hence the point under the greatest

hydrodynamic pressure. The square buildings, south and

on the hill north, have valves that can be closed to enable

repairs. A £23m programme to inspect and repair the

entire length of the aqueduct was begun in 2006, which

is the first time that the aqueduct has been completely

drained since it opened in 1894.

A few years ago, the platform across the aqueduct

was opened to walkers, which was much appreciated,

as also was the new bridge obviating the difficult ford

across Artle Beck, 0.5km below the aqueduct.

The Thirlmere Aqueduct (or Waterworks Bridge)

Artle Beck

Artle Beck acquires its name somewhere between

Crossgill and Potts Wood, by which point it has

already absorbed innumerable becks flowing into the

Littledale valley. From the north, Crossgill Beck runs

from the Caton wind turbines towards Roeburn Glade,

built on the site of the old Brookhouse Brick Company,

which closed down in the 1960s. Crossgill is probably

named after the ancient cross, marked on old maps, that

used to stand in the base that can be seen by a track (the

old Littledale Road) to the north. It is

an old farming hamlet: one building

bears a date of 1681. In 1780 a corn

mill was listed here – by 1850 it was

a bobbin mill, and it closed in 1945 as

a sawmill.

Right: The trig point and Ward’s Stone

Right: The trig point and Ward’s Stone

From the south, Foxdale Beck and

Udale Beck drain Blanch Fell and Black

Fell below Ward’s Stone (561m), the

highest point in the Forest of Bowland.

Ward’s Stone naturally affords a fine

view of the extensive plateaux of

southern Bowland, although the flat

top prevents views into the valleys. On

the top, erosion has exposed gritstone

boulders, some with fanciful names,

such as the Queen’s Chair. A few raised

islands of peat remain but generally

the surface is stony. After dry weather, it is dusty and the

gritstone sparkles in the sunlight but usually the sombre

colours intensify the wild, windswept remoteness.

The upland moors provide a breeding habitat for

birds such as curlew, snipe, redshank, ring ouzel, merlin,

golden plover, peregrine falcon, and hen harrier. The

last is the symbol of Bowland. The hen harrier is one

of England’s most threatened birds and Bowland is

its most important breeding site in England. In 2005

fifteen pairs nested in Bowland, more than in the rest

of England. Unsurprisingly, the Bowland Fells are a

Special Protection Area under the European Union’s

Wild Birds Directive.

[Update: The number of hen harriers nesting in Bowland

has declined. There were none at all in 2017 but there has been a slight increase since.

By an amazing coincidence, all the nests in the last decade were on United Utilities land, with none on

gamekeeper-managed grouse moors.]

Left: Littledale, looking up Udale Beck to Blanch Fell, with Ward’s Stone on the horizon

Left: Littledale, looking up Udale Beck to Blanch Fell, with Ward’s Stone on the horizon

The Littledale region is also a good one for observing

the lapwing, a bird that is distinctive in all three main

identifying characteristics: appearance (with a long

crest), flight (an acrobatic tumble) and call (a ‘pee-wit’).

The lapwing is declining drastically in other parts of the

country but in higher areas of Loyne where the sheep

numbers are not too high, such as Littledale, there has

been an increase.

The Black Side of Ward’s Stone is rough country

that until recently was reserved for grouse and grouse

shooting. The British record bag of 2929 grouse was made

in Littledale and Abbeystead on August 12th 1915. The

fine body of gentlemen (including four military officers

not distracted by the war on at the time) responsible for

this superlative achievement deserve naming: Major the

Hon. E. Beaumont, Capt. the Hon. H. Bridgeman, Major

the Hon. J. Dawnay, Capt. the Hon. T. Fitzherbert, Mr.

E. de C. Oakley, the Earl of Sefton, the

Hon. H. Stonor, and the Hon. J. Ward.

Today, it is CRoW land, open

to us all (except when the grouse-shooters decide to take priority, as they

are allowed to do on 28 days a year).

There’s an access point from Littledale

by Sweet Beck above Belhill Farm and

also a permissive path (not marked on

OS maps) from near Deep Clough by

Ragill Beck to Haylot Fell. Foxdale

Beck below White Spout and Cocklett

Scar is an attractive secluded spot. The

best walking is to be found on the ridge

that goes up to High Stephen's Head, for this is

mainly grass, in contrast to the heather,

bogs and rocks found below Ward’s

Stone.

Foxdale Beck passes Littledale Hall, which is not as

old as it looks. It was built in the Gothic Revival period

for the Reverend John Dodson, who had been Vicar of

Cockerham from 1835 to 1849. It became a Christian

retreat in 1988 and a rehabilitation centre in 2006. Near

the Hall is Littledale Chapel, also built by the Rev.

Dodson but now used as a barn.

It is sometimes worthwhile to pause and ask: Why?

Why did the Rev. Dodson leave his flock at Cockerham

to build a hall and chapel in Littledale? It was because of

the Gorham Judgement, a significant event in the history

of tension between church and state. A Mr Gorham had

been rejected as a vicar by the church because he did not

believe in its teachings on baptism but, after an appeal to

the Privy Council, the church had been overruled. Many

clergy strongly objected to a secular court overriding

spiritual authority, including our Rev. Dodson, who

set out to build a ‘free church’, as it says above the

doorway.

Right: Autumn mists over Artle Beck

Right: Autumn mists over Artle Beck

From Fostal Bridge Artle Beck runs through a deep

valley shaded by woodland, which is important for its

over 160 species of moss and liverwort, and past the

sites of coal mines at Hollinhead and Hawkshead that

were active until the early 19th century. On the opposite

bank is Stauvins Farm, which was the home of Harry

Huddleston (1910-2005). He was the first Englishman

to represent his country abroad at sheepdog trialling.

Sheepdog triallers do not rank high on the nation’s

sporting pantheon but for a section of the Loyne

community the magnificent name of Harry Huddleston

was one to be revered. He competed into his eighties

and when no longer able to walk operated from his car,

which he positioned next to the pen gate to help guide

the sheep. Nobody objected.

The beck emerges at Gresgarth Hall, the country

home of the internationally renowned garden designer

Lady Arabella Lennox-Boyd (oh, and Sir Mark Lennox-Boyd, former MP for Morecambe). As we would expect,

the gardens of Gresgarth Hall are impressive indeed,

having been transformed since 1978 from a gloomy,

dank, tree-shaded area, engulfed by rhododendron and

laurel, into a light, open parkland with terraced gardens,

herbaceous borders, a new lake, a water garden, an

orchard, a nuttery, and so on, with Artle Beck running

through them.

The gardens are open several times each summer,

usually in aid of the Conservative party, but don’t let that

put you off. Apart from the gardens, you will be able to

view the hall itself, which was largely rebuilt in the early

19th century. Perhaps you will be able to detect the rough

external masonry of the little that remains of the older

14th century hall.

The Gresgarth estate came into the ownership of

the historic Curwen family in 1330 when John Curwen

married Agnes de Caton. The Curwens owned extensive

land in Cumberland and Galloway when the England-Scotland border was more fluid. It is believed that after

the First War of Scottish Independence, which ended in

1328, John Curwen was granted the Gresgarth estate

(and dear Agnes, heiresses at that time being wards

of the crown) in compensation for losing his land in

Galloway.

John Curwen would have been well aware of the

threat from the Scottish, since Robert the Bruce had

ransacked Lancaster in 1322, and turned whatever

building then existed (thought to have been a rest home

for monks) into a tower house. The Curwens owned

the hall until the 17th century, since when it has passed

through many hands, including the Girlingtons, whom

we met as owners of Thurland Castle.

Below Gresgarth, Artle Beck is more sedate. In

the beck, opposite Bridge End, a Roman milestone was

found in 1803. It is usually said to be six foot high but it is

actually rather bigger, as can be checked in the Lancaster

City Museum. Its carvings indicate that it marked a point

four Roman miles from Lancaster, which is indeed the

straight-line distance to the Lancaster fort. It is therefore

an important indication of the path, now lost but probably

straight along this section, of the presumed road between

the forts at Lancaster and Over Burrow.

Artle Beck runs past Caton, which the afore-mentioned Thos Johnson considered “about the least

interesting of all the villages in the vale of the Lune.”

Although Caton is a workaday place this characterisation

is unfair because it doesn’t distinguish between the parish

and the village. Caton is old enough to be mentioned

in the Domesday Book but until relatively recently

Caton referred to four distinct communities: Littledale,

Caton Green, Brookhouse and Town End. The seat of

the manor, the original Caton Hall, was at Caton Green

and the parish church was at Brookhouse, which was, if

anywhere was, the centre of old Caton. Incidentally, the

present Caton Hall was the last home of the renowned

landscape architect, Thomas Mawson, who designed

many of Lakeland’s grand gardens and died here in

1933.

The Top 10 halls in Loyne

1. Gresgarth Hall

2. Underley Hall

3. Whittington Hall

4. Middleton Hall

5. Leck Hall

6. Burrow Hall

7. Ingmire Hall

8. Killington Hall

9. Ashton Hall

10. Thurnham Hall

It was only from the late 18th century that Town End

grew rapidly to become the industrial centre of Caton,

after the building of five mills. Ball Lane Mill was burnt

down in 1846; Rumble Row Mill and Forge Mill closed

down in the 1930s; Willow Mill and Low Mill continued

until the 1970s. The last three survive after conversion to

small business units and residences. Low Mill is reputed

to have been the oldest cotton mill in England, built in

1783 on the site of a corn mill that may have dated back

to the 13th century. A millrace taken from Artle Beck at

Gresgarth powered all the mills except Ball Lane. Its

route across Artle Beck near Forge Mill and through

Caton to Low Mill can still be traced. The millpond by

Low Mill is now a fishery. As with all becks off the hills,

the water supply was unreliable and Low Mill became

one of the first to use steam power in 1819.

All this activity led the centre of gravity of Caton

to move to Town End. This was confirmed by the

building of the turnpike road, the present A683, in 1812,

bypassing the old road through Brookhouse and Caton

Green, and by the arrival in 1850 of the railway, with

Caton Station.

This history explains the relative dearth of old

buildings in Caton. The oldest church is the Wesleyan

Methodist one of 1837. Many of the house names reflect

Caton’s practical past: the Rock m Jock cottages are

said to refer to the noise from the nearby Willow Mill;

Farrer House (which is an old building, dated 1680) is

the old blacksmith’s; the Ship Inn is supposed to refer

to the sailcloths produced at Willow Mill. Even the Fish

Stones are concerned with trade – the three semi-circular

slabs are where fish were sold in the Middle Ages. By the

Fish Stones is a very old oak tree, so decrepit that fears

that it is disobeying its preservation order prompted the

High Sheriff of Lancashire to plant a successor oak tree

in 2007.

[Update: The old oak tree continued to show little

sign of life and on June 20th 2016 was finally deemed to have passed away.]

The Fish Stones and ye olde oake treee in Caton

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (Wenningdale, Hindburndale and Roeburndale)

The Next Chapter (The Lune to Lancaster)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: The Wenning joins the Lune

Right: The Wenning joins the Lune

Left: The clay pit of Claughton brickworks

Left: The clay pit of Claughton brickworks

Right: The wind turbines on Caton Moor

Right: The wind turbines on Caton Moor

Right: An alien black swan joins the Lune avifauna

Right: An alien black swan joins the Lune avifauna

Right: The trig point and Ward’s Stone

Right: The trig point and Ward’s Stone

Left: Littledale, looking up Udale Beck to Blanch Fell, with Ward’s Stone on the horizon

Left: Littledale, looking up Udale Beck to Blanch Fell, with Ward’s Stone on the horizon

Right: Autumn mists over Artle Beck

Right: Autumn mists over Artle Beck