Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

References

Me

Saunterings: Walking in North-West England

Saunterings is a set of reflections based upon walks around the counties of Cumbria, Lancashire and

North Yorkshire in North-West England

(as defined in the Preamble).

Here is a list of all Saunterings so far.

If you'd like to give a comment, correction or update (all are very welcome) or to

be notified by email when a new item is posted - please send an email to johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com.

99. Heather on Hawthornthwaite Fell

According to the

Moorland Association,

heather moorland is “rarer than rain-forest” and “around 75% of Europe’s upland heather moorland is found in the

UK”. Therefore, it concludes, it is important to “protect and

preserve the moors” by continuing the management without which “the precious land would revert to scrub and

forest and the heather moors lost forever”. The conclusion seems ungrammatical – but, more importantly,

is it sound (assuming, for the sake of argument, that the premises are true)?

We set out from Grizedale Bridge to walk across the heather moorland of Hayshaw Fell,

Catshaw Fell, Hawthornthwaite Fell and Fellside Fell. Grizedale Bridge is

over Grizedale Brook, which arises a couple of miles to the east at Grizedale Head and flows below

Grizedale Fell, under the bridge, through Grizedale Reservoir and along Grize Dale to join the Wyre near Garstang.

If that isn’t enough Grizedales for you, there are plenty more (and lots of Grisedales and even a Grisdale) in

North-West England, the ‘grize’ or ‘grise’ being from the Old Norse for ‘pig’.

We soon met heather as we walked around Harrisend Fell and it accompanied us all the way for the three

miles to the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell. It was not particularly difficult walking, with the heather being of

variable height but never more than knee high and sometimes bone dry (the photo left, looking back along the fence

in the direction of Blackpool, shows, on the two sides of the fence, the heather in its two extreme states).

The heather's white and purple flowers were rather sparse but enlightened occasionally by the brighter bell heather. Overall,

though, the moor was sombre, as the promised blue skies had not fully materialised, with the dark heather covering the

whole expanse of the Bleasdale Moors.

We soon met heather as we walked around Harrisend Fell and it accompanied us all the way for the three

miles to the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell. It was not particularly difficult walking, with the heather being of

variable height but never more than knee high and sometimes bone dry (the photo left, looking back along the fence

in the direction of Blackpool, shows, on the two sides of the fence, the heather in its two extreme states).

The heather's white and purple flowers were rather sparse but enlightened occasionally by the brighter bell heather. Overall,

though, the moor was sombre, as the promised blue skies had not fully materialised, with the dark heather covering the

whole expanse of the Bleasdale Moors.

The wire fence went on and on to the top of the fell and so did we.

With no variety in our surroundings my mind wandered. I thought of

the botanist

Richard Salisbury

(1761-1829) who first recognised the unique nature of common heather (or ling). The

heather family (Ericaceae) has over 4,000 species within over 100 genera, including rhododendron, blueberry and

various heaths and heathers. Salisbury placed the common heather in a genus all of its own Calluna (from the Greek

for a besom, which heather used to be made into) when he noticed that the corolla and calyx are in

four parts instead of the five for the rest of Ericaceae.

Salisbury was a Yorkshireman and a difficult character (I’m saying nothing). He was born Richard Markham and changed his name in order to inherit from a relative of his grandmother. He suffered a series of financial difficulties and once spent time in a debtor’s prison in order to escape claims from his wife’s family. He moved from Yorkshire after acquiring a private botanic garden in London and became instrumental in establishing the Horticultural Society (now the Royal Horticultural Society). He became its first secretary in 1809 but he was soon forced to give up the role, with the Society’s accounts in disarray.

Unlike most of his fellow botanists, he did not accept the Linnean system, the taxonomy for biological

classification set up by Carl Linneaus in 1735. Salisbury preferred a ‘natural system’. He was further ostracised

by the botanic community for plagiarising another botanist, Robert Brown, who later became president of the Linnean

Society and after whom ‘Brownian motion’ is named. Brown commented that Salisbury “stands between a rogue and a

fool”. Well, he cannot have been a complete fool, as he did at least spot that

the corolla and calyx of common heather are in four parts.

However, he never saw a heather moorland like the one we were walking over.

We eventually reached the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell (478 metres) to find the trig point horizontal in the peat. In 2008 the trig point had been

upright (shown right) but standing like a tooth whose gum had rotted away to expose the root. The fact that

the trig point has since fallen is only of mild interest.

The question is: Why? Why has two or three metres of peat

disappeared in the century or so since the trig point was installed?

We eventually reached the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell (478 metres) to find the trig point horizontal in the peat. In 2008 the trig point had been

upright (shown right) but standing like a tooth whose gum had rotted away to expose the root. The fact that

the trig point has since fallen is only of mild interest.

The question is: Why? Why has two or three metres of peat

disappeared in the century or so since the trig point was installed?

As always, I don’t know but I am prepared to speculate. Peat forms from vegetation dying, decaying, and

being compressed into the soil, to grow millimetre by millimetre over the centuries. The Pennine hills have layers

of peat that may be several metres deep. Clearly, this process has been abruptly reversed here recently. In the

southern Pennines industrialisation has killed off vegetation, leading to erosion, but that it is unlikely to be

the explanation here, with the hills being in a rural part of Lancashire. The erosion cannot be blamed on walkers either,

because walkers were not allowed here until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act of 2000.

A major change in the last century or two has been that these moors have been rigorously managed. The core part of

that management is the practice of rotational burning whereby patches of heather are burned in a roughly ten-year

cycle so that there are always young green shoots for grouse to eat. This burning obviously reduces vegetation and

exposes the soil. In wet weather the soil will be more liable to be washed away, since it is less protected and

there is less vegetation to absorb the water.

In hot weather the soil will be more liable to dry out, become dusty and be blown away in a wind.

And once erosion is underway there may be little to stop it.

A major change in the last century or two has been that these moors have been rigorously managed. The core part of

that management is the practice of rotational burning whereby patches of heather are burned in a roughly ten-year

cycle so that there are always young green shoots for grouse to eat. This burning obviously reduces vegetation and

exposes the soil. In wet weather the soil will be more liable to be washed away, since it is less protected and

there is less vegetation to absorb the water.

In hot weather the soil will be more liable to dry out, become dusty and be blown away in a wind.

And once erosion is underway there may be little to stop it.

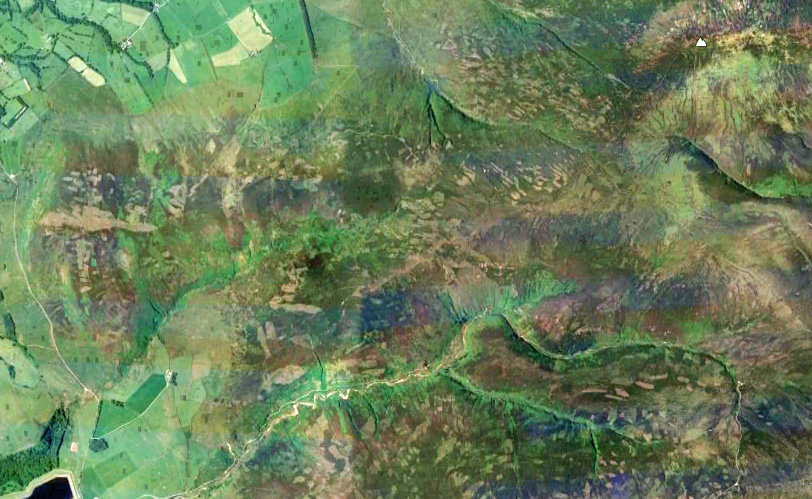

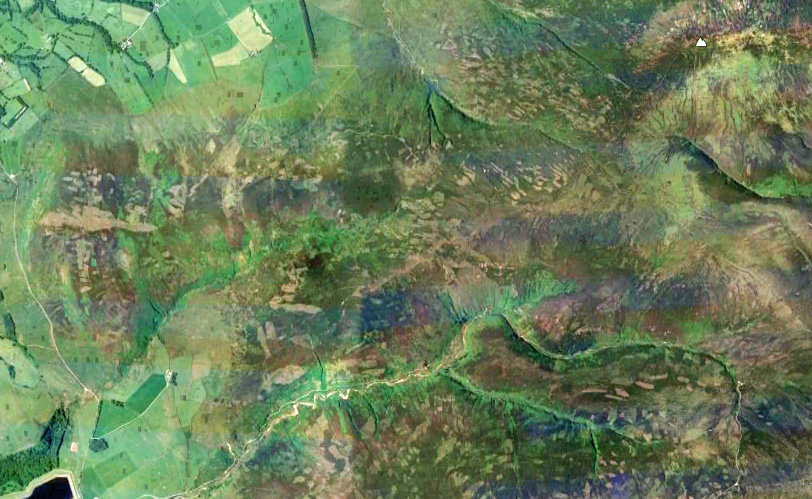

The effects of this burning are scarcely

noticeable at ground level, by a walker, other than in the variability of the heather. To appreciate the effect and

extent of the burning it helps to look at the Google Earth views of the hills.

The image to the left shows the moor that we walked

over, from bottom left to top right. If you use Google Earth to view the range of north Pennine hills

you will find that a great many of them show the distinctive signs of rotational burning, despite

being within National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and Sites of Special Scientific Interest.

The whole area that we walked over, and for miles around, is a patchwork of

recently burned heather.

The practice of rotational burning is controversial, for many reasons, but I don’t want

to engage with the controversy now: I want merely to point out that so-called heather moorland is clearly not a

natural environment. At least, it is rather less so than, say, a golf-course, which is maintained without such

destructive practices. In fact, the aerial view of managed moorland

looks much like a huge golf-course, but with more variations than its green, fairway and rough.

From the top we walked west across Hawthornthwaite Fell and Fellside Fell. There had been a rough path

beside the fence along the ridge top but there was no path here. It was a tiring struggle but we had

views across Morecambe Bay to see

Lake District rain clouds drifting our way but never quite making it. We passed various peat hags, wondering

how they came to be in the condition they’re in. We noticed young rhododendron and fir trees (which the sheep won’t

eat) and also a small silver birch (which the sheep hadn’t noticed yet) taking hold, perhaps indicating how these

moors might change if they were no longer managed. We also saw a raptor which wasn’t of a species that we

can normally identify. Perhaps it was a hen harrier? At long last, we were glad to reach the shooters’ track

by Catshaw Greave. Shooters’ tracks do have their uses.

Looking back to Hawthornthwaite Fell.

(According to the Moorland Association, heather moorlands are "treasured by millions of walkers and

wildlife enthusiasts". If that is the case then most of them treasure the moorlands as shown here - at

a distance. We saw nobody anywhere on the moors all day.)

So, to return to the original question: must we preserve our heather moorlands? Imagine that in the 19th century

some landowners had decided that large cypress hedges were a good idea to provide privacy (some did) and that

the practice caught on so much that we now had many square miles of tall, dense cypress forests – forming over

75%, say, of the world’s such forests and a habitat rarer than rain-forest.

Would we feel obliged to preserve them? Of course not.

They would be unnatural ecological deserts. As are our heather moorlands.

Date: August 3rd 2020

Start: SD535491, Grizedale Bridge (Map: OL41)

Route: NE – gate at junction of fences – NE, E – Grizedale Head, Greave Clough Head – NE –

Hawthornthwaite Fell Top – W across Hawthornthwaite Fell, Fellside Fell – shooters’ track by Catshaw Greave –

N – road – W past Isle of Syke Farm – SW, S on footpath on Harrisend Fell, S on road – Grizedale Bridge

Distance: 8 miles; Ascent: 315 metres

Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

References

Me

© John Self, 2018-

Top photo: The western Howgills from Dillicar;

Bottom photo: Blencathra from Great Mell Fell

We soon met heather as we walked around Harrisend Fell and it accompanied us all the way for the three

miles to the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell. It was not particularly difficult walking, with the heather being of

variable height but never more than knee high and sometimes bone dry (the photo left, looking back along the fence

in the direction of Blackpool, shows, on the two sides of the fence, the heather in its two extreme states).

The heather's white and purple flowers were rather sparse but enlightened occasionally by the brighter bell heather. Overall,

though, the moor was sombre, as the promised blue skies had not fully materialised, with the dark heather covering the

whole expanse of the Bleasdale Moors.

We soon met heather as we walked around Harrisend Fell and it accompanied us all the way for the three

miles to the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell. It was not particularly difficult walking, with the heather being of

variable height but never more than knee high and sometimes bone dry (the photo left, looking back along the fence

in the direction of Blackpool, shows, on the two sides of the fence, the heather in its two extreme states).

The heather's white and purple flowers were rather sparse but enlightened occasionally by the brighter bell heather. Overall,

though, the moor was sombre, as the promised blue skies had not fully materialised, with the dark heather covering the

whole expanse of the Bleasdale Moors.

We eventually reached the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell (478 metres) to find the trig point horizontal in the peat. In 2008 the trig point had been

upright (shown right) but standing like a tooth whose gum had rotted away to expose the root. The fact that

the trig point has since fallen is only of mild interest.

The question is: Why? Why has two or three metres of peat

disappeared in the century or so since the trig point was installed?

We eventually reached the top of Hawthornthwaite Fell (478 metres) to find the trig point horizontal in the peat. In 2008 the trig point had been

upright (shown right) but standing like a tooth whose gum had rotted away to expose the root. The fact that

the trig point has since fallen is only of mild interest.

The question is: Why? Why has two or three metres of peat

disappeared in the century or so since the trig point was installed?

A major change in the last century or two has been that these moors have been rigorously managed. The core part of

that management is the practice of rotational burning whereby patches of heather are burned in a roughly ten-year

cycle so that there are always young green shoots for grouse to eat. This burning obviously reduces vegetation and

exposes the soil. In wet weather the soil will be more liable to be washed away, since it is less protected and

there is less vegetation to absorb the water.

In hot weather the soil will be more liable to dry out, become dusty and be blown away in a wind.

And once erosion is underway there may be little to stop it.

A major change in the last century or two has been that these moors have been rigorously managed. The core part of

that management is the practice of rotational burning whereby patches of heather are burned in a roughly ten-year

cycle so that there are always young green shoots for grouse to eat. This burning obviously reduces vegetation and

exposes the soil. In wet weather the soil will be more liable to be washed away, since it is less protected and

there is less vegetation to absorb the water.

In hot weather the soil will be more liable to dry out, become dusty and be blown away in a wind.

And once erosion is underway there may be little to stop it.