Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

Saunterings: Walking in North-West England

Saunterings is a set of reflections based upon walks around the counties of Cumbria, Lancashire and

North Yorkshire in North-West England

(as defined in the Preamble).

Here is a list of all Saunterings so far.

If you'd like to give a comment, correction or update (all are very welcome) or to

be notified by email when a new item is posted - please send an email to johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com.

36. The Flow and Ebb and Flow of Morecambe

Ruth tipped me out of the car at the northern end of Morecambe Prom on her way to a rehearsal with the esteemed

Promenade Concert Orchestra.

I had four hours to fill before the concert. It seemed opportune to re-explore Morecambe because

just three days earlier the local paper had revealed plans for a proposed

Eden Project North in Morecambe.

If this project materialises – and everyone seems optimistic – then it will transform Morecambe and the

surrounding region.

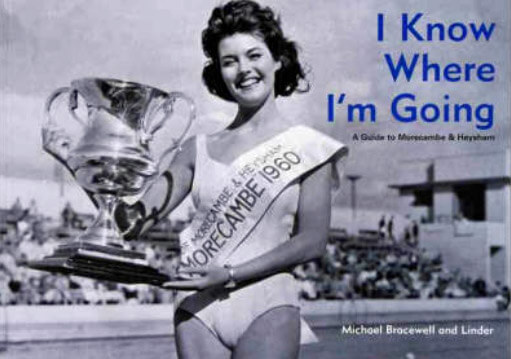

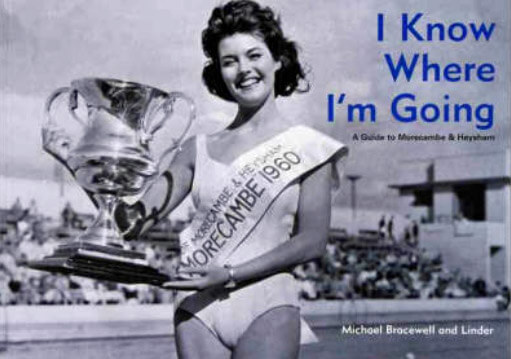

I was also inspired to have another look around Morecambe and Heysham after re-reading a quirky little

book published in 2003. At that time Morecambe was near its nadir as a seaside resort and yet the authors

were remarkably complimentary, whilst drawing a wistful contrast between past glories and the then tawdriness

(I suspect that they preferred the latter). The Midland Hotel had long been derelict and Frontierland,

the last tourist attraction of any note, had closed in about 2000.

No doubt, the nature of the book reflects

the nature of its authors,

Michael Bracewell and

Linder. The former is a cultural commentator who has written books on pop music and fashion. The latter

(full name Linder Sterling – she said in a

Guardian piece

that “one name seemed sufficient”, which perhaps it is if you spell it wrong) is an artist known

for her radical feminist photomontage. She was a key figure in the 1970s punk scene and in 2017

became artist-in-residence of Chatsworth House, suggesting some accommodation with the establishment.

Anyway, quite a couple to find the Morecambe and Heysham of 2003 interesting enough to write a book about.

I set off with the tide in, lapping at the new sea defences which cost £11m and were finished in 2018.

This is part of a programme to revitalise Morecambe’s seafront that had actually begun with government

funding in 1990. As a result, everything of interest to visitors overlooks the sea. Morecambe is lucky

not to have a view over the bay. It has many. Views when the bay is full (as on my walk), when the sandy mud stretches for miles across the bay, when (in the morning) the sun shines across the bay on the hills, when (in the evening) the sun sets over the sea or behind the hills, when it’s calm, when it’s choppy, and when it’s too misty to see anything.

Across Morecambe Bay

Perhaps the only exception to the seafront focus is Happy Mount Park, which I passed next. It is only

fifty metres from the sea but the sea is irrelevant to it. It is a traditional park, with gardens,

playgrounds and café, now fully recovered from the

Blobbygate

fiasco of 1994 when, in desperation at the resort’s falling income, the council embarked on a project that cost it millions. For the next mile all the sea-facing establishments seemed in fine order, with scarcely a ‘for sale’ sign or a hint of dereliction, and the Sunday morning walkers, joggers and cyclists were making the most of the November sunshine.

Surveys always suggest that Morecambe has a higher proportion of old visitors than other seaside resorts but you wouldn’t know it walking along this promenade. There was hardly an oldie to be seen. But then November is not the holiday season and no doubt most of the promenaders were local. Nearing central Morecambe, the average age of my co-walkers began to rise. I expect that it is true that the typical holiday visitor is rather old, which causes or is caused by a pervasive sense of nostalgia. As everywhere, the unchanging nature of the sea and the beach brings memories. For me as a boy, the seaside and holidays were synonymous: we always went to the seaside for holidays and we never went to the seaside except for holidays. I suspect that most Morecambe visitors are reliving their childhoods. Nostalgia is reminiscence plus regret: it is remembering how things were, whilst sadly accepting that those things can never return. There is nothing wrong with this – ‘heritage tourism’ is a perfectly respectable part of the business, but it is only part.

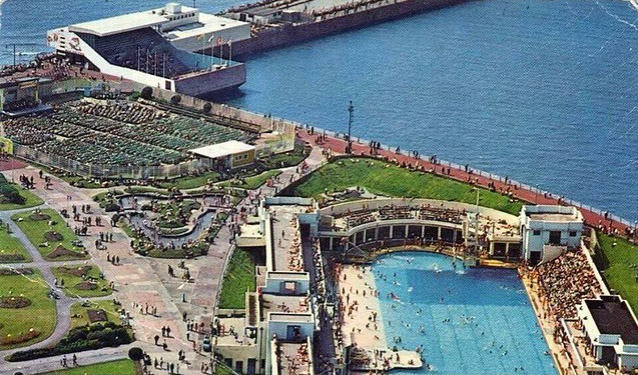

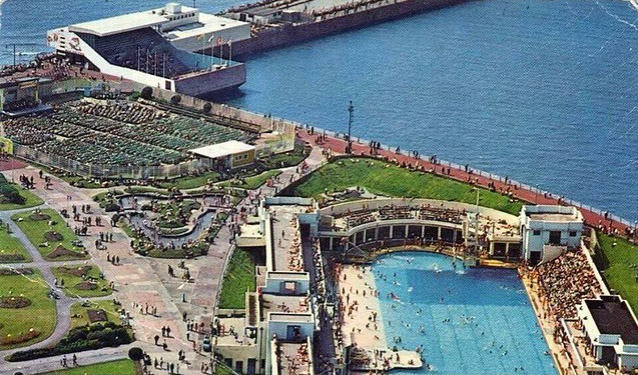

Right: Swimming Pool and Marineland, 1970s.

Right: Swimming Pool and Marineland, 1970s.

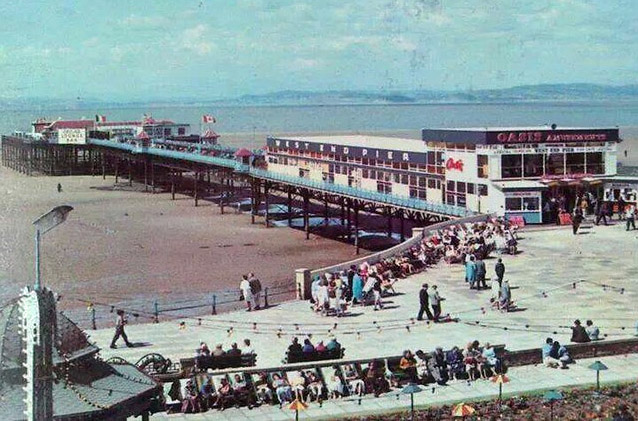

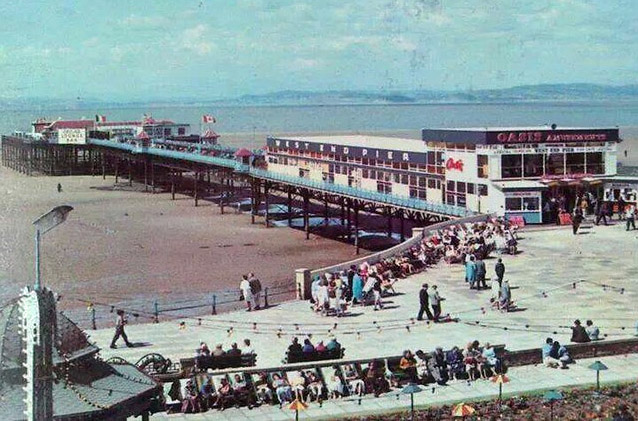

Left: West End Pier, 1970s

Bookshops of the past were never quite like the

Old Pier Bookshop.

Thankfully, it was closed – I didn’t have the time to get lost in the labyrinth of old books piled in no

discernible order. There is, of course, no pier adjacent. The two piers were demolished in 1978 and 1992.

I wandered among the back streets for a while, to confirm that they remain like the rust below a touched-up

car bonnet, and re-emerged near the site of the proposed Eden Project North. It is, as it needs to be, the

prime site in Morecambe, adjacent to the graceful, iconic Art Deco Midland Hotel. If I may presume to say

so, the Midland Hotel looked like it might need to be touched up itself if it’s to meet the standards that

will be set by the Eden Project North (if it happens). The Project’s proposed site is unused at the moment,

as it has been really since the open-air swimming pool was demolished in 1975. According to

this website,

the Super Swimming Stadium was “one of the grandest of the 1930s modernist seaside lidos” and “was said to be the largest outdoor pool in Europe when it opened in 1936”.

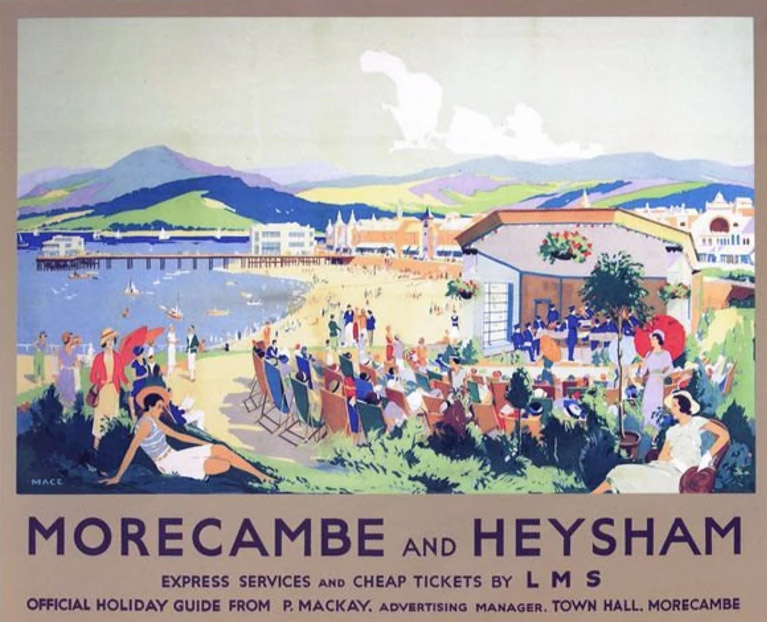

It is hard now to visualise Morecambe in its prime, the period of 1919-1957 or so, when it was

central to ‘the Sunset Coast’. Morecambe had flourished as a seaside resort after 1850 when the railway

enabled Yorkshire workers to flock there for their holidays. Morecambe had more visitors from Yorkshire

than Blackpool did, although many fewer in total. Bingham (1990) considered that Morecambe was at its

peak of popularity when well over 100,000 people came to see the illuminations switched on in 1949.

Morecambe’s wealth enabled it to develop a relative elegance, leading Bracewell and Linder to comment

that “more than any other seaside town, Morecambe has a claim to being the cradle of glamour and romance”

and that “the greatest modern articulation of this glamour” is the

Midland Hotel.

Or rather was, at the time they were writing. It was re-opened in 2008, confirmation of Morecambe’s developing renaissance.

The Midland Hotel

Morecambe was the well-publicised home of the Miss Great Britain contest from 1956 to 1989 but it took it on

at just the time that its fortunes began to plummet. From 1957 cinemas, theatres and much else besides began

to close, as holidaymakers came to prefer package holidays abroad. No seaside resort rose and fell faster

than Morecambe. By 1975 its plight had become a joke (to others), as shown – warning: on no account watch

anything outside the given times, it’s awful – by this

Youtube video

from 40.25 to 41.30. The bit from 40.25 is awful too. I only mention it because it shows that even a weedy funny-man with ridiculous hair and a punchable face felt able to put the boot in on Morecambe when it was down.

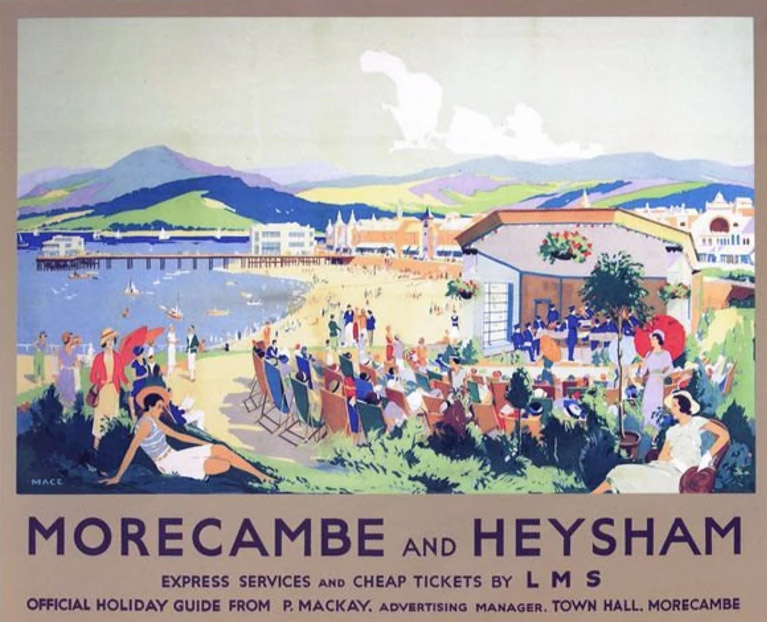

Right: Old LMS postcard for Morecambe and Heysham (with a concert underway).

Right: Old LMS postcard for Morecambe and Heysham (with a concert underway).

Actually, my memory is that Morecambe wasn’t so bad in the 1970s and 1980s. It provided a reasonable family day-out if your expectations were not set too high. There’s always a beach, or mud. Frontierland (or its then equivalent) was still alive, although it gradually withered and passed away. I walked past it next. Whatever is planned for the site seems not to have been activated yet. Similarly, for Morecambe’s West End, which was once a thriving part of the resort with its hotels and B&Bs. By the 1980s it was more for the unemployed than holidaymakers. In 2005 the North West Regional Development Agency began a programme to revive the West End but the Agency ended in 2010 after the financial crisis. Perhaps Bracewell and Linder had the West End in mind when they wrote that “a defining characteristic of Morecambe and Heysham … is an uneasy coexistence between the victims and the beneficiaries of acute consumerism”. In 2003 there were plenty of victims but not many beneficiaries.

The seafront here is more sombre than that seen to the north. There are more ‘for sale’ and ‘to let’ signs but not so many as to indicate that all hope has been lost. The back streets are struggling. I saw on the relatively grand West End Road that there were half-a-dozen ex-hotels for sale within spitting distance of the sea. The West End needs to be integrated with, not ignored by, central Morecambe. Would a shuttle bus (akin to Blackpool’s trams) that trundled between Happy Mount Park

and The Battery help? The Battery! It doesn’t sound appealing. Why not rename the area in honour of the

recently-demolished Grosvenor Hotel?

I strode on to Heysham, which seemed to enthral Bracewell and Linder. They wrote that “Heysham village is compositionally-perfect: all details balanced, all perspectives aligned to the luminescence of the seaward light” and that “in all weathers, the view from the headland retains its capacity to awe the viewer, mesmerising in its fully realised, ever-changing grandeur”. Well, they are artists, so they should know. I hadn’t fully appreciated Heysham’s perfection on previous visits but I was determined to do so now.

The Rose Garden, the Winged World (a bird zoo) and the go-kart track have long gone, and the

headland has been restored to a maritime heath by the National Trust, and, yes, there is a good view over

the bay from the rock graves. However, try as I might, I cannot see the village as compositionally-perfect, aligned to the seaward light. If anything, the old Main Street, charming as it may be in its way, has its back to the sea. It saddens me that I lack the artistic sensibility of the professionals.

The view from Heysham Head, looking the wrong way, to the port and the power station

The tide was turning and so was I. I sauntered back to The Platform, which was once the railway station at which the hordes to Morecambe arrived.

The concert provided an apt exercise in nostalgia. The orchestra played programmes from Music While You Work,

as heard on the wireless from 1940 to 1967. This light music was intended to raise the morale of ‘the workers’.

Nowadays we are too cynical to allow our morale to be lifted so easily. About 99% of the audience remembered the music

from the first time around and most, no doubt, regretted its disappearance from the wireless. Long may it not

disappear from Morecambe.

Date: November 25th 2018

Start: SD455657, near Scalestones Point (Map: 296)

Route: (linear) SW – Chapel Hill, Heysham – NE – The Platform,

Morecambe (plus digressions)

Distance: 7 miles; Ascent: 20 metres

Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

Map

References

Me

Drakkar

© John Self, Drakkar Press, 2018-

Top photo: The western Howgills from Dillicar;

Bottom photo: Blencathra from Great Mell Fell

Right: Swimming Pool and Marineland, 1970s.

Right: Swimming Pool and Marineland, 1970s.

Right: Old LMS postcard for Morecambe and Heysham (with a concert underway).

Right: Old LMS postcard for Morecambe and Heysham (with a concert underway).