The Land of the Lune

Chapter 15: Into Morecambe Bay

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Salt Marshes)

The road between Sunderland and Overton

The Lune from the Conder (continued) ...

The road south from Overton across Lades Marsh

leads to Sunderland, the end of the west bank of

the Lune. Unlike Overton, Sunderland has had

no new building for nearly a century. It looks like the

set for a film based in a 19th century fishing village, as

indeed it became in 2006 when used to film The Ruby

in the Smoke. With the tidal waters covering the road,

it is detached, both physically and mentally, from the

modern world.

Right: Second Terrace, from First Terrace

Right: Second Terrace, from First Terrace

It consists of two terraces, First Terrace and Second

Terrace, reasonably enough, and, a little apart, the

elegantly verandahed Old Hall, which bears a date of

1683. The hall became the home of Robert Lawson, a

Quaker merchant who built warehouses and workshops

at Sunderland for the complete building and fitting out of

ships. The houses all have their backs to the prevailing

westerly winds and hence have views across the estuary

to the masts of Glasson Dock and the Bowland Fells

beyond. There is even a glimpse of our old friend,

Ingleborough.

The terraced cottages are mainly 18th century, some

converted from the old warehouses. They have charm but

are not pretty as this is too tough a place for adornment.

A few cottages are named after the ‘cotton tree’, once

a feature of Sunderland but a victim of a gale in 1998,

after surviving for nearly 300 years. The tree was in fact

a female native black poplar, of which there are only two

in Lancashire (one is at Freeman’s Wood by Aldcliffe

Marsh). Or perhaps three, because there are apparently

shoots from the roots of the old Sunderland tree.

In front of the cottages a dozen boats rest at anchor

or doze on the mud, depending on the state of the tide. A

couple of them look like active fishing boats, a remnant

of the traditional occupation of Sunderland residents.

The heyday (such as it was, for Sunderland can never

have been much larger than it is now) was the period

from 1680, when it was recognised as a ‘legal quay’,

which meant that ships were allowed to unload goods

there, until about 1750, when St George’s Quay became

active. During that period, many ships avoided the

difficult journey up the Lune by having goods taken

ashore at Sunderland for transport across land or by

ferryboat to Lancaster. There was also a good trade in

towing or guiding boats up the estuary to Lancaster

but Sunderland’s business evaporated as fast as it had

begun, with the development of better docking facilities

in Lancaster, Fleetwood and especially Glasson.

After the demise of the port, Sunderland had an even

shorter-lived period of activity as a bathing resort. In the

early 19th century people became increasingly attracted

to sea bathing, although at first this was, for the sake

of propriety, not in the sea but in sea water within bath

houses. Sunderland was one of the first places to have

a bath house, with sea water being pumped into baths

at what was then the Ship Inn. By the 1830s, however,

the difficulties of access compared to Morecambe and

Heysham led Sunderland to become the quiet backwater

that it is today.

The most remarked upon feature of Sunderland

nowadays is that it is one of only two places in England

(the other being Lindisfarne) that is cut off twice a day

by the tide. However, this is only the case if lack of

vehicular access constitutes being cut off: Sunderland

can always be reached on foot from the west. It would

seem easy to provide a road on the landward side of

the flood embankment but no doubt the residents of

Sunderland want no more than the few visitors prepared

to make a committed effort to get there.

Left: Pebbles and old groynes (to reduce erosion) at Sunderland Point

Left: Pebbles and old groynes (to reduce erosion) at Sunderland Point

The best way to visit Sunderland, where there is not

really much space to park a car anyway, is to park at or

cycle to Potts Corner on the Morecambe Bay shore and

then walk south along the coast. There are magnificent

views across the bay, with the Fylde coast to Fleetwood

to the south, the south Lakes coast to the Isle of Walney

to the north, and on the horizon the glinting blades of the

offshore wind turbines.

The mud and sea stretch for miles, glittering in the

sunlight and providing spectacular sunsets. There is the

odd abandoned craft and the perhaps odder individual

who feels confident enough about the tides and the mud

to venture far off shore but it is the enormous numbers

of wading birds that catch the eye. Morecambe Bay is

said to be the most important estuary in England for

its seabird and waterfowl populations, especially for

over-wintering birds – greylag geese, mallard, red-breasted merganser, pink-footed geese, pintail, pochard,

shelduck, shoveler, wigeon, and so on. Over 160 species

have been recorded. They are attracted, of course, by the

food in the mud, which may look unappetising to us but

contains, for example, about 5000 Baltic tellins, which

are small shellfish, per square metre (I have taken the

experts’ word for this).

If you keep your eyes to the west, as you should, you

will miss Sambo’s Grave, which is to be recommended.

This is apparently a tourist attraction but it is a tawdry

and maudlin site, a poignant but pathetic memorial

to our own inglorious past as much as to Sambo, a

slave who died at Sunderland in 1736: “here lies poor

Sambo: a faithful Negro”, isolated as a heathen unfit for

consecrated ground.

If you must look landward, look instead for the

Belted Beauty moth. This endangered moth has colonies

at only three sites in England and Wales and, until the

colony at Sunderland was confirmed in 2004, it was

thought to live only on coastal sand dunes. Here its

habitat is salt marsh, with sea rush and autumn hawkbit.

The males fly at night, as moths tend to do, and rest

during the day; the poor females are wingless.

Searching for moths in salt marsh is not to everyone’s

taste but the moths’ existence here is an indication

of the special nature of this vulnerable promontory.

If you continue the walk south to Sunderland Point

(there is no public footpath but I don’t think anyone

will object), you’ll see that the fields, some 2m above

beach level, are virtually unprotected and appear to be

crumbling fast under the western gales.

[Update: The point is now protected by large boulders.]

Right: Hang glider over Sunderland

Right: Hang glider over Sunderland

From the end of the promontory, we can see across to

the Plover Scar lighthouse and may fear that our journey

down the Lune and its tributaries has come to an end. But

if the beginning of a river is always a matter of debate,

so is its end. At high tide the Lune is 1km wide from

Sunderland Point and disappears into the wide expanses

of Morecambe Bay, but at low tide the Lune can be

considered to continue for a further 7km or so between

Cockerham Sands and Middleton Sands before finally

joining the waters of Morecambe Bay at the Point of

Lune. According to the Environment Agency by-laws,

the Lune estuary lies landward of a line from Knott End

jetty to Heysham No. 2 buoy and thence to Heysham

lighthouse. For the sake of completeness, then, we will

take the Point of Lune as the end of our story, which will

enable us to include the gentle tributaries of the River

Cocker and Broad Fleet.

Plover Scar lighthouse

[Update: I received a nice letter from a man who recognised himself

and his wife in this photo. Actually, I think he recognised the boat! He said that he had made the

boat a few years earlier copying "a boat [his] grandfather had built 99 years ago in Overton on the

style of the local salmon fishing 'wammel' boats."]

The River Cocker

Left: Lancaster Canal near Winmarleigh

Left: Lancaster Canal near Winmarleigh

Right: Ellel Grange

The Cocker is barely large enough to be a river but is

not sprightly enough to be a beck. It arises north of

Cocker Clough Wood on a ridge between the Conder and

the Wyre, carefully avoiding both. It runs past Hampson

Green, under the M6 and railway line, past Bay Horse,

and is joined by Potters Brook just before crossing the

Lancaster Canal.

Potters Brook flows from Forton, known to many

through the distinctive Forton (recently renamed

Lancaster) Service Station, with its tower no longer a

restaurant-cum-viewpoint. For travellers from the south

the tower marks a gateway to the dramatic northern

landscapes. Forton has long been on travellers’ routes:

before the railway and canal, the Roman road from

Lancaster passed here, probably by Forton Hall Farm

and Windy Arbour. Today, Forton consists mainly of new

bungalows, plus the 1707 United Reformed (formerly

Independent) Church, with bright yellow door to enable

it to be located in the overgrown churchyard.

The Cocker swings north towards Ellel Grange.

This Italianate villa, as it’s always described, was built

in 1859 for William Preston, who became High Sheriff

of Lancashire in 1865. It is said to be modelled on Queen

Victoria’s Osborne House (completed in 1851), but then

so are innumerable contemporary British villas. The

grange is now the international headquarters and Special

Ministries Unit of the Ellel Ministries.

The Ellel Ministries make the name of Ellel known to

people throughout the world but few of those people are

aware that the name refers to a tiny village near Lancaster.

The story of the Ellel Ministries begins in 1970 when Peter

Horrobin was repairing a sports car and – here I must quote

from their website so that you don’t think me lacking in

due seriousness – “God spoke to him about how he could

straighten the chassis and rebuild the car, but much more

importantly, God could rebuild broken lives.” And if He

whispered ‘Ellel’ that was fortunate because apparently in

old English it means ‘all hail’.

When Ellel Grange came up for sale in 1985 Horrobin

raised nearly £0.5m from supporters to convert the grange

into a ministry. The Ellel Ministries are now an international

brand with branches in Australia, Canada, Germany, India,

Norway, Singapore, South Africa and the United States.

What do the Ellel Ministries do? This may be as

treacherous as the sands of Morecambe Bay, but I will

venture in. The mission is “to proclaim the Kingdom of

God by preaching the good news, healing the broken-hearted and setting the captives free.” In practice, this

means “discipleship, healing and deliverance training”.

The theology, however, is controversial. According

to others, the Ellel Ministries have “extreme doctrinal

positions on deliverance and demonology” that “are void of

biblical foundations”. A review of Horrobin’s book Healing

through Deliverance concluded that it argued that “those

who did not believe that Christians can be demonized …

are themselves demonized.” Verily, I should steer clear, at

least until my broken heart needs healing.

The Cocker continues south past Cockerham,

flowing under Cocker House Bridge, where there is

an old boundary stone. Cockerham is an old village,

appearing in the Domesday Book as Cocreham. Its

church, thought to have been founded in the 11th century

and rebuilt in the 17th century, 1814 and 1911, is a plain,

sturdy structure standing apart from the village.

At the north end of Cockerham is the vicarage built

in 1843 for the Rev. Dodson, whom we met in Littledale.

The earnestness we saw there is seen also in his

determination to rid Cockerham of all sinful activities,

such as cock fighting, hare coursing, horse racing and

even bowling. After the Rev. Dodson left, a public house

was built in 1871 without, it seems, unduly disturbing

the peace of the village. Apart from the pub, the only

other establishments in Cockerham today seem to be a

beauty salon and a funeral directors. I’m not sure if the

Rev. Dodson would approve of the implicit philosophy

of life.

The Cocker dawdles through flat land drained by

many ditches in Winmarleigh Moss. This is Lancashire’s

largest remaining uncultivated peat mossland,

supporting rare insect species such as the large heath

butterfly and bog bush cricket. Winmarleigh itself is

a scattered village. Winmarleigh Hall was built on the

site of Old Hall in 1871 for John Wilson-Patten, MP

for Lancashire North for 42 years. He became Baron

Winmarleigh, the first and last, as he outlived his two

sons and grandson. The hall is now owned by NST Travel

Group, which claims to be “Europe’s largest educational

and group travel company”. Residential visitors can

tackle a variety of challenging activities set out in the

grounds of the hall.

Beyond Cocker Bridge, the Cocker runs between

sea defence embankments built in 1981. In 1969 the

only colony of natterjack toads in Lancashire had been

found on Cockerham Moss. Natterjack toads are the

rarest of six British amphibians and are protected by

law. The site was washed over by the highest tides but

not after the wall was built. Perhaps coincidentally, the

colony became extinct after 1981. The Herpetological

Conservation Trust is now trying to restore the habitat

and reintroduce the natterjack toad.

Part of Cockerham Moss was enclosed only after

draining in the 19th century. The few buildings are

modern and of brick. The terrain is flat and featureless,

given over to sheep and cattle, with some arable farming

if dry enough.

Similarly, north of the Cocker Channel, lies the

flat drained land of Thurnham Moss. At the seaward

extremity of this bleak landscape are the remains of

Cockersand Abbey. The meagre remains today do

not indicate the extent and importance of the abbey.

Originally, the abbey stood up to where the sea wall is

now. Today, there are just a few stones scattered about

with only the chapter house still standing, partly because

it was used as a burial place after being adopted by the

Daltons. The red sandstone masonry of the old abbey

was re-used in nearby farm buildings and in the sea wall,

a somewhat ironic use of the stones since the abbots

lived in fear of being submerged by the sea.

The remains of Cockersand Abbey

Cockersand Abbey was established as a monastic cell

in the 12th century by Hugh the Hermit, as he would need

to have been to choose this bleak, exposed, otherwise

godforsaken spot, cut off from the mainland by Thurnham

Moss. By 1190 this St Mary’s of the Marsh had become a

Premonstratensian abbey.

The abbey became very rich during the 13th century,

through being granted much land in the northwest of

England. At that time people were desperate to go to

heaven and believed that a prayer on their behalf from

monks would help. A gift to the abbey proved your piety.

The monk’s life was not entirely one of cloistered

contemplation. According to British History Online: in

1316, the abbey suffered badly from Scottish raids; in 1327,

a canon was pardoned for the death of a brother; in 1347,

the abbot and four canons were accused of using violence;

in 1363, the abbey was ravaged by plague; in 1378, the

king was begged for special compensation because “each

day they are in danger of being drowned and destroyed

by the sea”; in 1402, there was fear of violence from

parties with whom they were in litigation; in 1488, two

apostate canons were excommunicated, the brethren were

forbidden to reveal the secrets of the order, and two other

canons were accused of breaking their vow of chastity; in

1497, the canons were forbidden to “exchange opprobrious

charges” and to draw knives upon one other; in 1500,

various diseases were attributed to “inordinate potations”

and there were minor disorders, such as disobedience to the

abbot, lingering in bed and neglecting services on pretext

of illness.

It all gives new meaning to the Dissolution of the

Monasteries. At that time (1539) Cockersand was the

third richest abbey in Lancashire. Its annual income was

estimated at £157, revised (to no avail) to £282 after it was

decreed that monasteries with an income less than £200

would be taken over by the king. Its lands, valued at £798,

were bought by John Kechyn of Hatfield in 1544 and then

passed to Robert Dalton of Thurnham Hall.

Beyond the sea wall and embankment the Cocker

disappears into the mudflats of the Lune estuary and

Morecambe Bay, forming part of the Wyre and Lune

Sanctuary Nature Reserve, established as a national

wildfowl refuge in 1963. This affords protection for

internationally important numbers of wintering knot,

grey plover, oystercatcher, pink-footed geese and

turnstone. It also provides an important staging post for

birds such as sanderling. The embankment runs 8km

west, past the village of Pilling, and is crossed through

flood gates by Wrampool Brook and Broad Fleet.

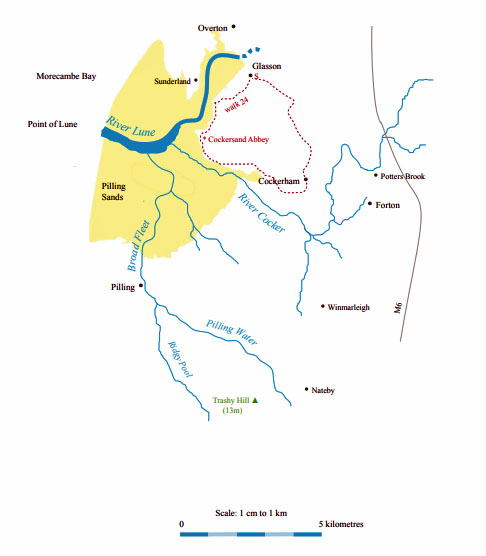

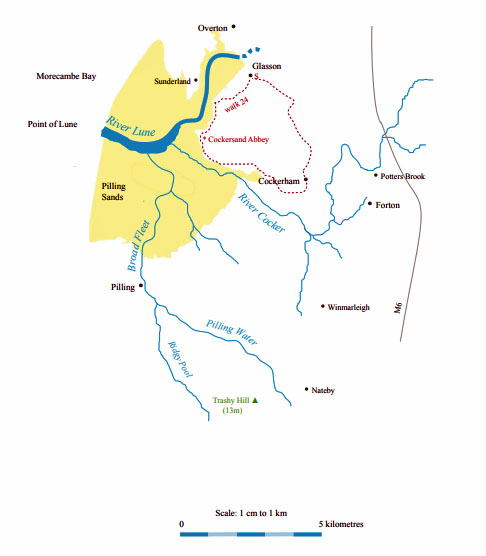

Walk 24: Glasson, Cockersand Abbey and Cockerham

Map: 296 (please read the general note about the walks in the

Introduction).

Starting point: Near Glasson marina (446561).

This is a walk best done on a grey, rainy day with a strong westerly wind and a high tide – to better get into the spirit of the

place. (Only joking.)

Walk southwest through Glasson to Tithe Barn Hill, and then turn right along Marsh Lane to Crook Farm. Follow the sea

wall south to the Abbey Lighthouse Cottage, Plover Hill (7m high) and Cockersand Abbey, to which make a short detour. Across

the shimmering waters of Morecambe Bay, Fleetwood and the Isle of Walney may be seen.

Continue past Bank Houses and the Cockerham Sands caravan park, and along the 1km embankment. Turn right towards the

Patty’s Farm holiday cottages, before which you cut southeast through the Black Knights Parachute Centre, which may be busy

with planes and parachutists (but not if you’ve chosen a windy day). Across the fields, turn left on the A588 for 200m, and then

walk to St Michael’s Church. From the church take the path northeast to the Main Street of Cockerham.

Walk north through Cockerham and take the path northeast to Batty Hill. Continue north along a muddy track and then walk

northeast to Cock Hall Farm (the high point of the walk, at 27m). Turn northwest past Thurnham Church and walk through the

Thurnham Hall Country Club and across a field to Bailey Bridge. Cross the bridge and stroll along the canal towpath back to

Glasson.

[Update: It is best not to tackle this walk after a period of heavy rain,

when the fields will be waterlogged and the 'muddy track' I mentioned will be a pond.

I am advised that the footpath at Cock Hall Farm has been altered to go around the farm.]

Short walk variation: Follow the long walk past Bank Houses to the end of the embankment and then turn left instead of right.

Walk north either past the fishery of Thursland Hill or through Norbreck Farm, renowned for its pedigree Belgian Blue cattle.

Either way you will eventually reach Moss Lane. Continue due north, either across fields or on a quiet lane to the east, to cross

the canal and then turn left to the marina.

Broad Fleet

Broad Fleet slides into the Lune estuary from Pilling

Moss, via its tributaries of Pilling Water from

Nateby and Ridgy Pool from Eagland Hill. In the Lake

District a ‘water’ is a lake; Pilling Water is not a lake

but it flows little faster than one. And Ridgy Pool flows

like a pool.

Nateby and Eagland Hill are 10m above sea level

and some 10km from the Lune. Obviously, the region is

flat. There are long, wide views over large, rectangular

fields for cows, sheep and intensive crop production.

Given the monotonous terrain perhaps I should argue

that Broad Fleet is not really a tributary of the Lune and

not bother with this section. However, there is nowhere

that some expert in something doesn’t find engrossing.

Unfortunately for the visitor, the main interest here

is underground, where recent studies have revealed

unexpected insights into the past, present and possibly

future of Pilling Moss.

Right: The rather serious Nateby church

Right: The rather serious Nateby church

The story begins with the Ice Age, when boulder clay

was dumped over the Fylde region, leaving occasional

small drumlins. By 4000 BC, the region had become a

forest, as shown by the large number of ‘moss stocks’,

that is, old tree trunks uncovered in the fields and dated

to that period. The roots were upright and the trunks had

been hacked off, showing that the trees were felled and

that there was a large local community to carry out this

arduous work.

This is supported by extensive finds of Neolithic

implements and the discovery of ancient earthworks

around Nateby. Today, the gentle undulations in the

fields appear unremarkable but aerial photographs reveal

various regular shapes, such as a 200m-diameter henge

dated to about 2500 BC. Many Bronze Age remains have

been found north of Nateby.

With the forest removed, the region became

heathland but after the climate became damper in about

1400 BC it slowly turned into a bog, a process thought

to have been complete by 800 BC. Old tracks, formed

by laying down tree trunks to cross the bog, have been

dated to that time. Over the centuries, layers of peat were

formed, the first 1m or so being of rough peat, from the

heathland vegetation, and then up to 4m of softer peat,

mainly from sphagnum moss. The extent of the bog can

be judged by the place names on today’s map: I counted

eight Moss Sides and three Moss Edges surrounding an

area of about 25 sq km.

During the investigations of the Nateby earthworks

a Roman road (or by-road) was discovered. It has been

traced to join the Roman road that we’ve followed

south from Lancaster and is believed to have continued

west, south of Pilling Moss, to meet a port on the River

Wyre. In the following centuries, habitation was limited

to the drumlins raised a metre or two above the bog.

Many farmsteads were drolly given a name with ‘hill’

in it. Unsurprisingly, there are few old buildings of

architectural merit. For example, the village of Nateby,

mainly a row of semi-detached houses today, was little

more than a church a century ago. The new buildings in

the region are mostly of red brick.

[Update: Experts now seem to doubt that what was discovered

was a Roman road. They seem unsure about the henge mentioned above too.]

Left: The weather-vane at Island House

(exaggerating the steepness of the island a little)

Left: The weather-vane at Island House

(exaggerating the steepness of the island a little)

Pilling, however, is an old village, being owned by

Cockersand Abbey in the 12th century and passing to the

Dalton family in the 16th century. It was very isolated,

having the sea to the north and Pilling Moss to the

south. There are only two buildings that interrupt the flat

horizons: Damside mill and the church steeple.

The windmill was built in 1808 to a height of

22m, the tallest in Fylde. By the 1940s it had become

derelict but, rather miraculously, it has been restored

as a residence, complete with a traditional ‘boat top’,

installed in 2007. It puts into perspective a proposal for

two 125m wind turbines at Eagland Hill, which was

rejected in 2008.

Right: Damside mill, Pilling

Right: Damside mill, Pilling

The steeple belongs to the St John the Baptist

Church built in 1887 by Paley and Austin again. Here,

they not only tackled the novelty (for Loyne) of a steeple

but enlivened it by using different coloured stones, such

as pink ones for the parapet. The church replaced one

that still stands in the field behind, with a date of 1717

over the door and a sundial bearing the name of George

Holden, who in Pilling literature is said to have “devised

the modern tide tables”.

On this journey I have learned to be wary of simply

repeating such claims. The facts are far from simple.

Holden’s Liverpool Tide Tables, said to be the first

high-quality such tables, were published for many years

from 1770. There were three George Holdens involved.

George I (1723-1793) was vicar of Pilling Church from

1758 to 1767, after which he moved to Tatham, to become

curate there until he died. George II (1757-1820) lived

in Horton-in-Ribblesdale, where he was a schoolmaster,

from 1783. He succeeded George I to the Tatham curacy

but still lived in Horton. George III (1783-1865) was

the curate at Maghull near Liverpool from 1811. I am

relieved that George III had no children.

The publication of the tide tables was passed on as a

lucrative family side-line. Notwithstanding the fact that

George I lived in the Pilling parsonage right beside the

tidal floodgates, Pilling’s pride in its involvement seems

exaggerated, for three reasons. First, the original tide

tables were published by brothers, George I and Richard

(1718-1775). Richard was a teacher in Liverpool,

specialising in mathematics and navigation. He seems

the more likely to have had the necessary skills to prepare

the tide tables. Secondly, the Holdens’ closely-guarded

‘secret method’ was checked against the meticulous data

gathered by William Hutchinson, the Liverpool dock

master. This data was never returned and I can find no

details of the ‘secret method’. Hutchinson himself had

theories about lunar effects on tides and the extent to

which the Holdens were dependent upon him is unclear.

Thirdly, none of the tide tables were produced while

George I was actually in Pilling: the Georges beavered

away on the tables while in Tatham, Horton and Maghull.

(I bet you wish now that I had just repeated the claim.)

Left: Pilling from Lane Ends

Left: Pilling from Lane Ends

Today, Pilling Moss is farming land, crisscrossed by

many ditches. It was drained in the 19th century, after

which it was possible to lay a railway line across it in

1870. The single-line track ran, rather informally, from

Garstang to Pilling and, later, Knott End. The ‘Pilling

Pig’, named from the sound of the engine or whistle,

became a familiar feature, and today a model of it stands

at Fold House as one of the few things for tourists to

look at. The line closed for passengers in 1930 and for

freight in the 1950s.

Once the bog had been drained, the peat began to

shrink and much of it was cut for fuel, an activity that

ended in the 1960s. The farmland is now lower (leaving

some lanes perched 1m or more above it), the rich soil is

disappearing, and, who knows, the area is ready for its

second flooding.

This is precisely what the Pilling Embankment

built in 1981 is intended to prevent. In the meantime,

the embankment provides (from the section open to the

public between Lane Ends and Fluke Hall) a view of

Broad Fleet seeping into Morecambe Bay, and of the

Lake District hills behind Heysham Power Station and,

suitably enough, of where we began, the Howgills, far

behind the Ashton Memorial. And to show that I am not

alone in considering this still to be within Loyne, the last

house as the road peters out beyond Fluke Hall is called

Lune View Cottage.

Broad Fleet entering Morecambe Bay

Here’s a fascinating fact that I’ve kept up my

sleeve in order to finish this flat Fylde section with a

flourish: when it’s in the mood, the River Lune can bring

700,000,000,000 litres of water into Morecambe Bay in

one day. We now know where they all come from.

Reflections from the Point of Lune

And so, at the Point of Lune, the waters of the Lune

and all its tributaries finally merge into Morecambe

Bay and the Irish Sea. The final sentence of Return to the

Lune Valley (2002) concludes that a tour down the Lune

valley is “an interesting journey and a pleasant one”.

‘Pleasant’ is perhaps as positive as one can be about the

Lune valley itself but it is possible to support a claim

that the wider area within the Lune watershed is the most

varied of any river in England.

Natural England has produced an analysis of

England in terms of 159 ‘National Character Areas’,

that is, areas that are “distinctive with a unique ‘sense of

place’”. The Loyne region includes parts of ten of these

National Character Areas. No other English river of the

size of the Lune and its tributaries, if any at all, passes

through so many Character Areas. In the following

review of our journey, the Character Areas are indicated

in italics.

The River Lune rises in the Howgills, which are

composed of ancient sedimentary rocks that have been

eroded into steep, rounded, grassy hills, incised by swift-flowing becks and grazed by sheep, but largely devoid of

people. As the Lune swings west, on its northern side are

the Orton Fells, composed of limestone. Below dramatic

limestone pavements, there is fertile soil supporting

improved pasture.

At Tebay, the Lune turns south and is joined by

becks from the western Howgills and, from the west,

from the Birkbeck and Shap Fells, part of the Cumbria

High Fells. Below Sedbergh, the Lune forms the western

boundary of the Yorkshire Dales Character Area, which

is not the same as the National Park. From the Yorkshire

Dales the major tributaries of the Rawthey, Dee, Greta

and Wenning flow. This part of the Yorkshire Dales

is mainly of limestone, overlain with sandstone and

siltstones, capped by millstone grit on the highest tops. It

includes some of the best limestone scenery in England,

with impressive pavements, gorges, potholes and cave

systems.

As the Lune continues south of Sedbergh, its western

watershed is much closer than that to the east. The rolling

semi-improved, upland pastures from Firbank Fell down

to Kirkby Lonsdale form part of the South Cumbria

Low Fells, which stretch west towards Windermere and

Coniston. From Kirkby Lonsdale the west bank of the

Lune forms the eastern fringe of the Morecambe Bay

Limestones Character Area, which extends to Kendal

and Ulverston.

To the east of the Lune south of Kirkby Lonsdale

is the Bowland Fringe, an area of lush pasture, hay

meadows, woodlands, marshes and becks, in which there

are many isolated stone farmsteads and small villages.

The pace of change is slow and many prehistoric features

survive, including traces of Roman roads. The Lune and

its tributaries are notable for the number of medieval and

later halls and manor houses, later adapted for a variety

of contemporary uses.

As the Lune flows on in its widening floodplain,

it is joined by becks from the Bowland Fells, an area

of millstone grit forming a wild, windswept, upland

plateau of bog and heath. Just north of Lancaster, the

Lune becomes tidal and enters the Morecambe Coast

and Lune Estuary Character Area. Here the low-lying

land is covered with glacial and alluvial deposits and

was once an area of fens, marshes and bogs. Today, it has

been largely drained to provide pasture but there are still

extensive areas of inter-tidal marshes. Finally, joining the

Lune estuary, are rivers and drainage channels from the

flat lands of the northern Fylde, part of the Lancashire

and Amounderness Plain.

From this great variety of landscape types derives

a range of human activities, although the Lune and

its tributaries remain relatively undeveloped. It also

provides such varied scenery and specific habitats for

wildlife that much of the area has been recognised

nationally and internationally, through designations as

parts of National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural

Beauty and Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Most

of the region is farmed but even the areas that seem

most like wilderness require a delicate balance between

conservation and development, between the past and the

future.

Even within such an apparently timeless region as

Loyne, the threat of the future looms. On many mornings

I set off to investigate a part of Loyne without a cloud

in the sky. As the day progressed and the boots became

muddier and the legs became wearier, so the sky often

became hazier. But this was usually not a natural haze.

It was caused by the vapour trails of the jets crossing

the Loyne skies. The Loyne is on a busy flight path:

often I could count a dozen or more jets in the sky at

one moment.

As I wander on the green hills and among the grey

villages of Loyne, many thousand people a day cross

the skies above me. Clearly, I am misguided. I am

envious of people who have acquired a sufficiently deep

appreciation of their local surroundings and can, in a

week or two, similarly appreciate wherever they are off

to. Perhaps I should join them, but I suspect that I will

look forward most to seeing those green hills and grey

villages out of the jet’s windows as I return.

The last view of the Lune, at high tide from the embankment beyond Fluke Hall,

with the Bowland Fells in the distance

References

Abram, Chris (2006), The Lune Valley: Our Heritage (DVD).

Alston, Robert (2003), Images of England: Lancaster and the Lune Valley, Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd.

Ashworth, Susan and Dalziel, Nigel (1999), Britain in Old Photographs: Lancaster & District, Stroud: Budding Books.

Baines, Edward (1824), History, Directory and Gazetteer of the County Palatine of Lancaster.

Bentley, John and Bentley, Carol (2005), Ingleton History Trail.

Bibby, Andrew (2005), Forest of Bowland (Freedom to Roam Guide), London: Francis Lincoln Ltd.

Birkett, Bill (1994), Complete Lakeland Fells, London: Collins Willow.

Boulton, David (1988), Discovering Upper Dentdale, Dent: Dales Historical Monographs.

British Geological Survey (2002), British Regional Geology: The Pennines and Adjacent Areas,

Nottingham: British Geological Survey.

Bull, Stephen (2007), Triumphant Rider: The Lancaster Roman Cavalry Stone, Lancaster: Lancashire Museums.

Camden, William (1610), Britannia.

Carr, Joseph (1871-1897), Bygone Bentham, Blackpool: Landy.

Champness, John (1993), Lancaster Castle: a Brief History, Preston: Lancashire County Books.

Cockcroft, Barry (1975), The Dale that Died, London: Dent.

Copeland, B.M. (1981), Whittington: the Story of a Country Estate, Leeds: W.S. Maney & Son Ltd.

Cunliffe, Hugh (2004), The Story of Sunderland Point.

Dalziel, Nigel and Dalziel, Phillip (2001), Britain in Old Photographs: Kirkby Lonsdale & District, Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd.

Denbigh, Paul (1996), Views around Ingleton, Ingleton and District Tradespeople’s Association.

Dugdale, Graham (2006), Curious Lancashire Walks, Lancaster: Palatine Books.

Elder, Melinda (1992), The Slave Trade and the Economic Development of 18th Century Lancaster, Keele: Keele University Press.

Garnett, Emmeline and Ogden, Bert (1997), Illustrated Wray Walk, Lancaster: Pagefast Ltd.

Gibson, Leslie Irving (1977), Lancashire Castles and Towers, Skipton: Dalesman Books.

Gooderson, Philip (1995), Lord Linoleum: Lord Ashton, Lancaster and the Rise of the British

Oilcloth and Linoleum Industry,

Keele: Keele University Press.

Gray, Thomas (1769), A Guide to the Lakes, in Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire, Kendal: Pennington.

Halton Rectory (1900), Annals of the Parish of Halton.

Harding, Mike (1988), Walking the Dales, London: Michael Joseph.

Hayes, Gareth (2004), Odd Corners around the Howgills, Kirkby Stephen: Hayloft.

Hayhurst, John (1995), Glasson Dock - the survival of a village, Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies.

Hindle, Brian Paul (1984), Roads and Trackways of the Lake District, Ashbourne: Moorland Publishing.

Hindle, David and Wilson, John (2005), Birdwatching Walks in Bowland, Lancaster: Palatine Books.

Hudson, Phil (1998), Coal Mining in Lunesdale, Settle: Hudson History.

Hudson, Phil (2000), Take a Closer Look at Wenningdale Mills, Settle: Hudson History.

Humphries, Muriel (1985), A History of the Ingleton Waterfalls Walk, Ingleton Scenery Company.

Hutton, Rev. John (1780), A Tour to the Caves, in the Environs of Ingleborough and Settle, in the West-Riding of Yorkshire. With

some Philosophical Conjectures on the Deluge, Remarks on the Origin of Fountains, and Observations on the Ascent and

Descent of Vapours, occasioned by Facts peculiar to the Places visited, Kendal: Pennington.

Johnson, David (2008), Ingleborough: Landscape and History, Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing.

Johnson, Lou, ed. (2005), Walking Britain (on-line guide).

Johnson, Thos (1872), A Pictorial Handbook to the Valley of the Lune and Gossiping Guide to

Morecambe and District.

Jones, Clement (1948), A Tour in Westmorland, Kendal: Titus Wilson & Son.

Kenyon, David (2008), Wray and District Remembered.

Lancashire County Council (2006), Lancaster: Historic Town Assessment Report, Preston, Lancashire County Council.

Lancaster Group of the Ramblers’ Association (2005), Walks in the Lune Valley.

Lord, A.A. (1983), Wandering in Bowland, Kendal: Westmorland Gazette.

Marshall, Brian (2001), Cockersand Abbey, Blackpool: Landy.

Mason, Sara (1994), The Church and Parish of Tunstall.

Mitchell, W.R. (2004), Bowland and Pendle Hill, Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd.

Mitchell, W.R. (2005), Around Morecambe Bay, Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd.

Moorhouse, Sydney (1976), Twenty Miles around Morecambe Bay, Morecambe: Trelawney Press.

Morton, H.V. (1927), In Search of England, London: Methuen.

Pearson, Alexander (1930), The Annals of Kirkby Lonsdale and Lunesdale Today, Kendal: Titus Wilson & Son.

Penney, Stephen (1983), Lancaster in Old Picture Postcards, Zaltbommel: European Library.

Raistrick, Arthur, Forder, John and Forder, Eliza (1985), Open Fell Hidden Dale, Kendal: Frank Peters.

Roskell, Ruth Z. (2005), Glimpses of Glasson Dock and Vicinity, Blackpool: Landy.

Routledge, George (1854), A Pictorial History of the County of Lancaster.

Salisbury, John (2004), Nateby and Pilling Moss: the Pre-Historic Legacy, Pilling: Sue White.

Sellers, Gladys (1986), The Yorkshire Dales: a Walker’s Guide to the National Park, Milnthorpe: Cicerone Press.

Sharp, Jack (1989), New Walks in the Yorkshire Dales, London: Robert Hale.

Shotter, David and White, Andrew (1995), The Romans in Lunesdale, Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies.

Slater, David et al (1989), The Complete Guide to the Lancaster Canal, Lancaster Canal Trust.

Speight, Harry (1895), Craven and the North West Yorkshire Highlands, London: Elliot Stock.

Stansfield, Andy (2006), The Forest of Bowland and Pendle Hill, Tiverton: Halsgrove.

Swain, Robert (1992), Walking down the Lune, Milnthorpe: Cicerone Press.

Trott, Freda (1991), Sedbergh, Sedbergh: T.W. Douglas & Son.

Trott, Stan and Trott, Freda (2002), Return to the Lune Valley, Kendal: Stramongate Press.

Wainwright, Alfred (1970), Walks in Limestone Country, Kendal: Westmorland Gazette.

Wainwright, Alfred (1972), Walks on the Howgill Fells, Kendal: Westmorland Gazette.

Wainwright, Alfred (1974), The Outlying Fells of Lakeland, Kendal: Westmorland Gazette.

Wainwright, Martin, ed. (2005), A Lifetime of Mountains: the Best of A. Harry Griffin’s Country Diary, London: Aurum Press Ltd.

Wellburn, Alan R. (1997), Leck, Cowan Bridge and the Brontës.

White, Andrew (1990), Lancaster: a Pictorial History, Chichester: Phillimore & Co. Ltd.

White, Andrew, ed. (1993), A History of Lancaster, Keele: Ryburn Publishing.

White, Andrew (2004), Life in Georgian Lancaster, Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing.

Wildman, Dorothy (2004), Caton as it was.

Williamson, Peter (2001), From Source to Sea: a Brief History of the Lune Valley.

Wilson, Stephen (1992), Geology of the Yorkshire Dales National Park, Skipton: Yorkshire Dales National Park Committee.

Wilson, Sue, ed. (2002), Aspects of Lancaster, Barnsley: Wharncliffe Books.

Winstanley, Michael, ed. (2000), Rural Industries of the Lune Valley, Lancaster: Centre for North-West Regional Studies.

Back Cover Blurbs

“This is not a walking book although it does give 24 descriptions of walks and it’s not a history book - and does give

more history of the area than most of us dreamt of. The Land of the Lune is best described as a book of the Lune

landscape. It uses the language and stories of people who live there now and in past centuries, but I am left with a more

powerful impression of the hills, valleys and rivers that will outlast us all. John Self has clearly explored the Lune

Valley thoroughly. His love for the landscape comes through in his words complemented by his colour photography.”

(Lancaster Guardian, in describing its “Books of 2008”)

“... 230 extremely interesting pages on the areas of the Lakes, Yorkshire Dales and Lancashire through which the Lune

makes its way to the sea via Morecambe Bay.” (The Dalesman Magazine)

“The Land of the Lune is a guide to the region within the Lune watershed ... areas of England we know and love for

reasons which become obvious as you flick through this glossy paperback and see some of the stunning images captured

on camera ... Well-known peaks, pathways, becks and bridges litter the 230 pages and the author visits man-made

features of interest as well as exploring the way the landscape has developed over the centuries ... It is well-researched

and comprehensive.” (Westmorland Gazette)

“The Lune is one of Cumbria’s overlooked rivers, perhaps because the county has to share it with Yorkshire and

Lancashire ... Yet between its birth in the Howgill Fells and its end in Morecambe Bay its sixty-six miles drain a vast

area of hill country, claiming parts of Mallerstang, Whernside, Ingleborough and the Forest of Bowland in its domain.

John Self traces the course of the river and its tributaries with a collection of walks to help readers explore this unfairly

neglected watercourse.” (Cumbria Magazine)

“ ... a quality guide to the region of northwest England that lies within the Lune watershed. Filled with detail and colour

photographs.” (Carnforth Books)

“I would like to offer my congratulations on a fascinating and masterly piece of work. The range of your study is vast,

and I have learnt a great deal about an area which I thought, mistakenly, I knew something about!” (JS, Caton)

“If you have produced and published this beautiful book ‘all by yourself’ then I am amazed!!” (JH, Stockport)

“My wife recently gave me your book which I have enjoyed immensely. It is the first one where the author has delved

into the furthest reaches of the tributaries.” (JT, Kirkby Lonsdale)

“An extremely interesting and well produced book with a lot of information for anyone interested in visiting that area

of Cumbria and Lancashire.” (A review on Amazon)

“The book is well written by someone with a sense of humour and provides the keen walker and those just seeking

information about the Howgill hills a great reference book ... A real good read.” (Another review on Amazon)

“... a very nice book, obviously loads of research, good pictures and well written.” (LS, Preston)

“... attractive and helpful to a rambler like myself.” (JI, Lancaster)

“I enjoyed every page, and it won’t be long before I start all over again - as you do with excellent books.” (RH,

Bangor)

Carlin Gill from Grayrigg

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Salt Marshes)

© John Self, Drakkar Press

Right: Second Terrace, from First Terrace

Right: Second Terrace, from First Terrace

Left: Pebbles and old groynes (to reduce erosion) at Sunderland Point

Left: Pebbles and old groynes (to reduce erosion) at Sunderland Point

Right: Hang glider over Sunderland

Right: Hang glider over Sunderland

Left: Lancaster Canal near Winmarleigh

Left: Lancaster Canal near Winmarleigh

Right: The rather serious Nateby church

Right: The rather serious Nateby church

Left: The weather-vane at Island House

(exaggerating the steepness of the island a little)

Left: The weather-vane at Island House

(exaggerating the steepness of the island a little)

Right: Damside mill, Pilling

Right: Damside mill, Pilling

Left: Pilling from Lane Ends

Left: Pilling from Lane Ends