Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

References

Me

Saunterings: Walking in North-West England

Saunterings is a set of reflections based upon walks around the counties of Cumbria, Lancashire and

North Yorkshire in North-West England

(as defined in the Preamble).

Here is a list of all Saunterings so far.

If you'd like to give a comment, correction or update (all are very welcome) or to

be notified by email when a new item is posted - please send an email to johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com.

172. Out to Pasture in the District of Eden

The book Walking Through Spring (Hoyland, 2017) describes a walk from the Dorset coast

to the Scottish Borders in step with the north-advancing spring. Referring to the region

north of Kirkby

Stephen it says that

“This district of Eden has the lowest population density of any district of England

and Wales, and most people would say it is one of the most beautiful parts of the country, too”.

The second part of that sentence, which is a matter of opinion, is not unrelated to the first part,

which is a matter of fact (I assume). However, the relative absence of people does not mean

that the region is one of natural beauty. Little that is natural remains. The region

is devoted to farming, generating a landscape of rolling green pastures.

I set off from the village of Winton, a name which apparently derives from the Old

English for a pasture farmstead. It is said to have been at the centre of sheep rearing in

the Eden valley in the Middle Ages. Today, the village is quiet, off the A685, and with mainly

red sandstone cottages amongst which the three-storey Manor House with a date of 1726 looks out

of place, like a modern office block, but perhaps reflecting a period of wealth. There is still

the aroma of farming, with the occasional tractor or quad-bike pottering about.

Left: Winton, with the prominent Manor House;

Right: The first fields beyond Winton.

Beyond the village I entered the first of many red-soiled, green-grassed fields, all

with open views across to the Pennines, from which the clouds were gradually dispersing in the

February sun. After a mile I reached the smaller village of Kaber. Today the name of Kaber

means little but in 1663 it featured in the ‘Kaber Rigg plot’, an unsuccessful rising against

Charles II, after which the leaders were hanged at Appleby.

I crossed the tiny but nicely-named Popping Beck and, after eluding some over-inquisitive

sheep, reached Belah Bridge over the River Belah. Like Kaber, Belah is a name once better known,

in this case for the

Belah Viaduct,

which used to cross the Belah three miles or so upstream. This

remarkable structure was the highest bridge in England (at 60 metres)

when it was constructed in 1860. Sadly, it was demolished in 1963. The

walk east on the north bank of the River Belah was a delightful stroll, with the unexpected sight

of Belah Scar, a red sandstone cliff of 40 metres or so towering on the south bank.

Left: The River Belah from Belah Bridge;

Right: Belah Scar.

After passing Brough Sowerby Common, a narrow strip of rough common land forming the

only piece of non-farmed land in the region, I reached the village of Brough Sowerby. This

consisted of a line of modern houses leading, I expect, to the core of the old village to the

west but I didn’t walk that far, instead cutting north to Sowerby Park.

From a rise beyond Sowerby Park there is a fine prospect north of the Pennine hills.

Below them cuts the A66, with traffic proceeding serenely over the

Stainmore Pass, one of

the main cross-Pennine routes. The Romans recognised it as such by building their camps at

Stainmore on their route between Carlisle and Ermine Street and at Brough, just below me,

they had their fort of

Verteris.

Within the fort are the remains of

Brough Castle,

built in 1092 and abandoned in the 17th century.

Looking to the Pennines from near Sowerby Park, with Brough Castle to the left

Left: Brough Castle from the bridleway to Great Musgrave;

Right: Swindale Beck.

I walked west along a bridleway that eventually reached Swindale Beck, crossing it at

the farm of Hall Garth. I then left the bridleway in order to walk through the village of Great Musgrave,

which is, of course, not great at all but slightly bigger than the nearby Little Musgrave.

This seemed to be very much a farming community with, as far as I could tell, at least four

active farms in the two Musgraves. I began to wonder about all this farming. I appreciate that farming is a

complicated business – much too complicated for non-farmers to comment on, farmers say – but can I

ask naïve questions, such as “Which of the many farms that I passed on this walk is the best farm?”

Crossing Musgrave Bridge over the River Eden, I had a straightforward walk back to Winton

on lanes and tracks, rather than across yet more pastures. The long, narrow, straight lane south from Little Musgrave

was wedged between high hedges, as is typical of the region. There was no

traffic but halfway along I could see, rather surprisingly, a walker approaching from the distance.

We neared like two gunfighters ready to draw arms, but he drew first, saying “We’ve got a busy road

here.” I could only agree, although he was mistaken.

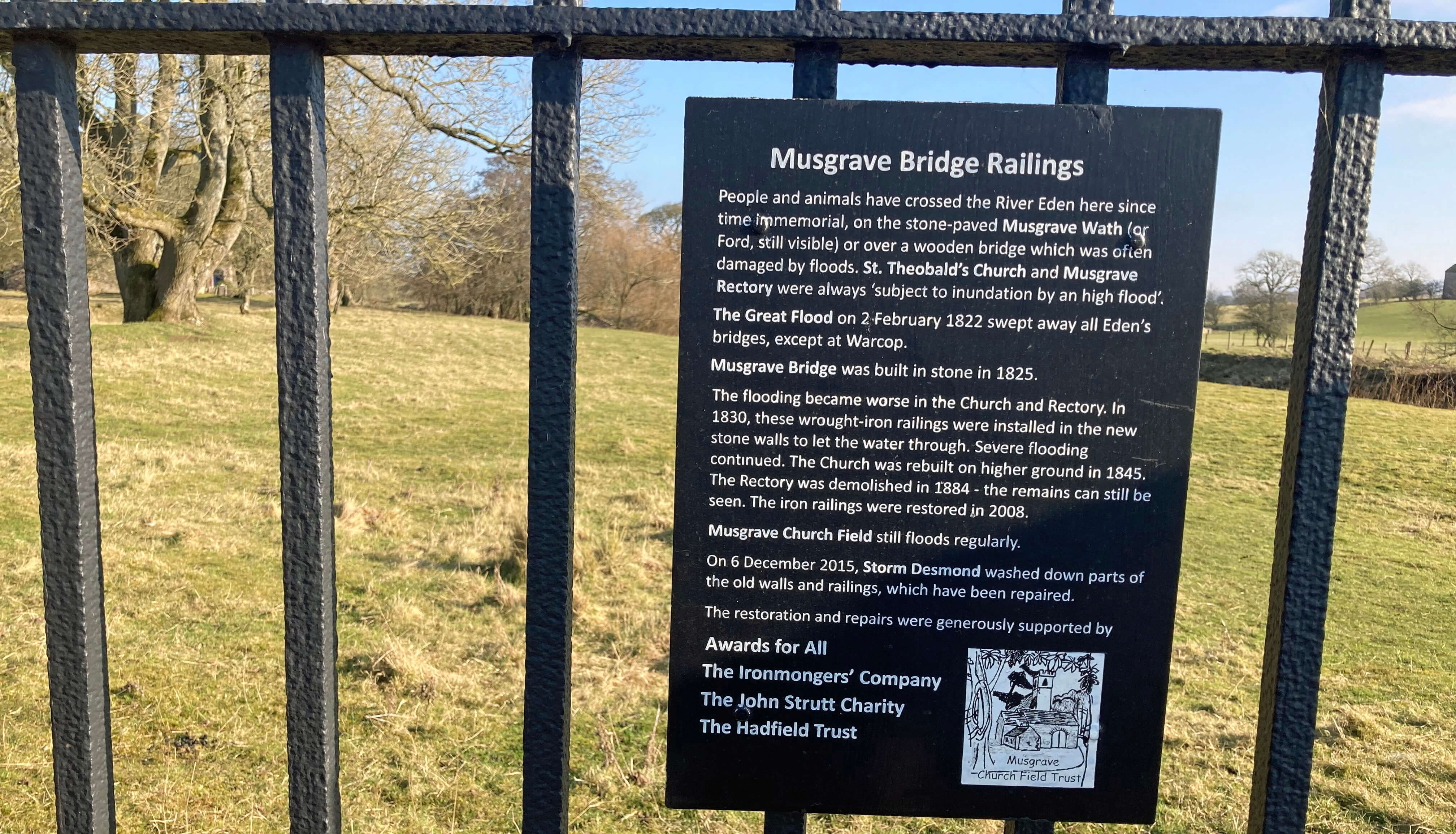

Left: Great Musgrave;

Right: Musgrave Bridge.

The sun directly ahead provided spring-like warmth although mid-February was much

earlier than when Hoyland passed this way (early June) on his walk in step with spring.

In my drowsiness I came to pondering the nature of farming. The separation between farming (as food

production) and nature conservation that the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside

Act rather formalised by establishing NNRs and SSSIs, which were later supplemented by the SPAs and

SACs of the EU, was mitigated in 1985 by the EU’s ESA framework and England’s CSS and WES,

although these were phased out and replaced in 2005 by the ESS, with ELS and HLS, including

a HFA and UELS for upland farmers, to go further than the SPS to maintain land in GAEC as

approved by the RDPE of DEFRA.

Now that we have left the EU, farmers, having mastered all those acronyms [*], can probably

forget them and start learning some new ones, beginning with ELM, for Environmental Land Management

(plus SFI (Sustainable Farming Incentive) and CS (Countryside Stewardship)).

I need to put ELM into context. Farming is an industry similar in some respects to, say, coal-mining, car-making

and ship-building but successive governments have not left farming to market forces. Farmers receive

considerable subsidies, totalling £3,297 million in 2021.

There are about 192,000 farms in the UK but don't bother to work out the average subsidy per farm

because the subsidies are distributed very unevenly. About half of the farms are under 50 acres.

For small farms such as, I suppose, those

that I had walked past, subsidies make up 78% of their profits, on average. These subsidies are

considered to be justified by the fact that we can live, up to a point, without coal, cars and ships,

but we cannot live without food.

Of course, farming is about more than a product. It is also about the custodianship of

much of our environment. Farmers have received payment for improving water quality, reducing

soil erosion, improving conditions for wildlife, reducing flood risk, protecting the historic

environment, providing public access, and so on. All of this is, I understand, to be expanded

and formalised in the new ELM scheme. Farmers will be able to claim for up to 280 actions that protect the environment.

I appreciate that our environment needs help but I’d be hard pushed to list 280 actions

that would definitely help it. Most actions have pros and cons. Consider, for example, the action

of introducing beavers. Who is to decide what actions should be on the list? Will those

farmers who have already been carrying out environmentally-friendly actions be, in effect,

penalised? For example, our Eden farmers who have carefully protected the hedgerows that are such

a feature of the region will be less able to claim subsidies for planting new hedges (if that is one of the 280).

Who is to administer

this scheme? DEFRA is short of funds already. It will need an army of inspectors (like

Ofsted for schools) to visit all the farms and check all these actions. There’ll be scope

for nods and winks and, dare I say it, backhanders.

But I mustn’t pour polluted water on

the scheme – its heart seems to be in a better place.

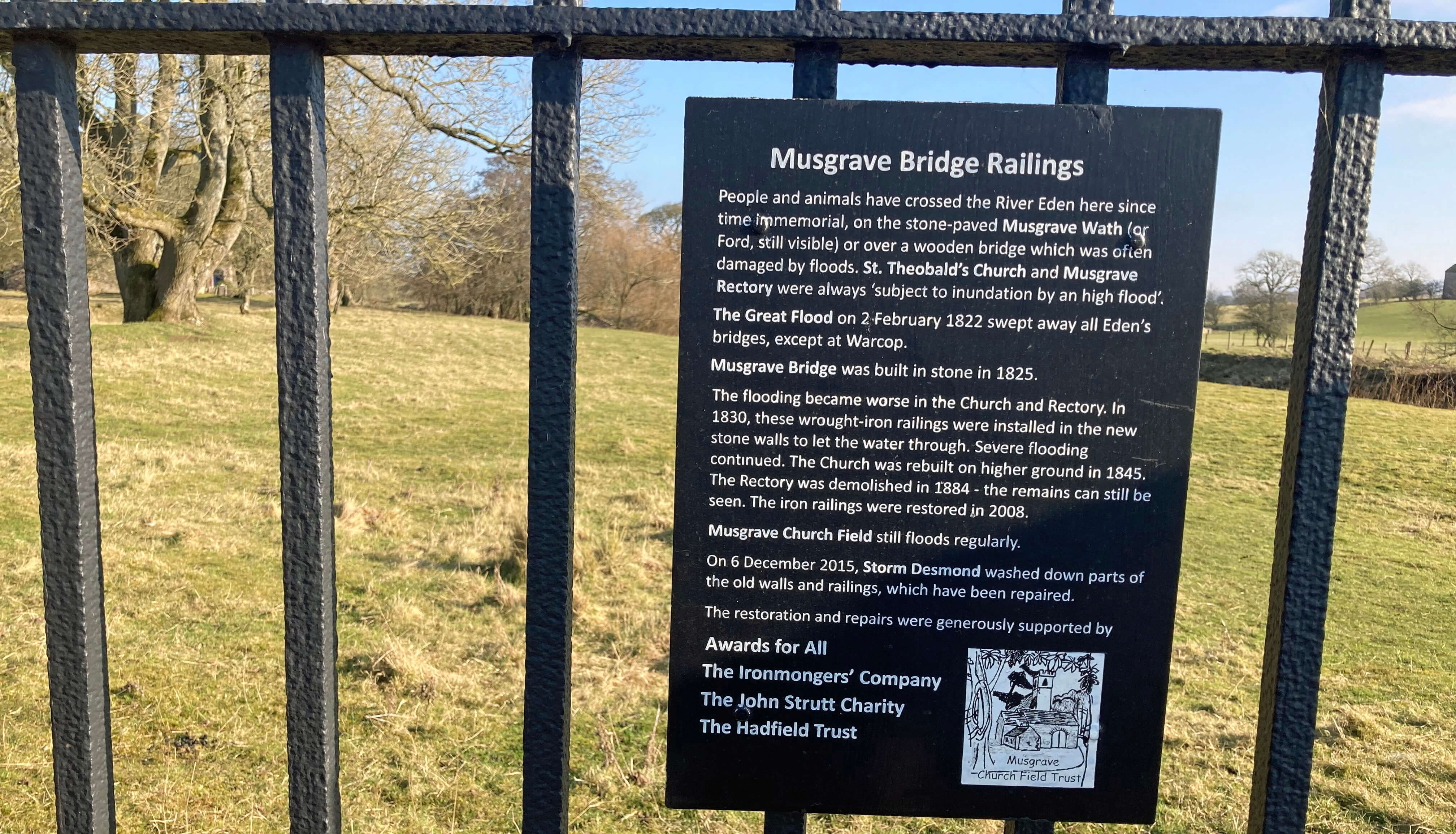

For light relief from the serious issue of farming here are three signs seen along the way.

Left: A sign affixed to a post - I don't know what it signifies other than that this is a farming region;

Middle: An old AA sign on a house in Little Musgrave (there's a similar one in

Great Musgrave) - again I don't know why;

Right: A sign near the Great Musgrave church headed "Musgrave Bridge Railings". I've never seen a

sign extolling the merits of railings before. The notice is mainly about the troubles

of the church which is liable to flooding, since it's right by the river.

The surprising thing to me about all these subsidies, over many decades and, I suspect, in

the future, is how secretive it is, considering that the farming activity is clearly intended for the

public good. To receive subsidies farmers must supply voluminous data to

DEFRA. This data and the subsidies awarded remain confidential to DEFRA, as far as I am aware.

This is in contrast to hospitals, universities, schools, county councils, railways, the police

and so on. These bodies are perpetually harassed to provide data so that they may be ranked under

all conceivable headings, all in the cause of creating a competitive market where one doesn’t naturally

exist, and so that, in principle, the public can make a judgment about whether it is receiving value for money.

It might be objected that farms are much too complicated for meaningful statistics. But

are farms any more complicated than the above-mentioned institutions? In any case, the Rural

Payments Agency, which is an “executive agency sponsored by DEFRA” (whatever that precisely means),

awarded ‘points’ to any farm wanting a stewardship payment. And points meant prizes. A farm with

30 points per hectare qualified for an ‘entry level’ award. So the data did exist and will

presumably continue to do so under ELM.

I, for one, would like to be able to find out how much public money a farm receives and

what actions a farmer has promised to carry out. I would be happier

walking through farms if I knew they were helping the environment.

You’d think that it would be in the farming industry’s own interests to publicise such information,

to develop goodwill with the public. There must be reasons why DEFRA and the farming industry

prefer to keep these arrangements to themselves. The only reason I can think of is that the

bulk of the subsidies went to the already-rich landed gentry, who didn’t want us to know.

(For example, some serious sleuthing enabled the

'Who Owns England' website

to report that the Duke of Westminster, who owns

grouse moors in Bowland, received £815,805 in 2015.) Perhaps

that will change under the new scheme, but I doubt it.

So the answer to my naïve question is: I don’t know and it is impossible for me or

anyone else to know, without the data.

Left: Scandal Beck (and snowdrops);

Right: The River Eden.

At the end of the long lane from Little Musgrave I turned east on what was signed

as a by-road to Winton. Is ‘by-road’ a legally defined term? Anyway, this was not a road

for cars, as they could not possibly cross the river. It was a track, much like the long lane,

except that it had never been tarmacked and therefore gave an impression of what all these

little lanes once looked like. And then over the Eden again and, after hopping into the

hedge to avoid the various tractors, back to Winton.

[*] The acronyms are: NNR - National Nature Reserve; SSSI - Site of Special Scientific Interest: SPA - Special Protection Area; SAC - Special Area for Conservation; ESA - Environmentally Sensitive Area; CSS - Countryside Stewardship Scheme; WES - Wildlife Enhancement Scheme; ESS - Environmental Stewardship Scheme; ELS - Entry Level Stewardship; HLS - Higher Level Stewardship; HFA - Hill Farm Allowance; UELS - Uplands Entry Level Stewardship; SPS - Single Payment Scheme; GAEC - Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition; RDPE - Rural Development Plan for England; DEFRA - Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Date: February 13th 2023

Start: NY785105, Winton (Map: OL19)

Route: NE – Kaber – N – Belah Bridge – E by River Belah, N, W – Brough

Sowerby – N – Sowerby Park – NW, W, SW by Swindale Beck, N – Hall Garth – W through Great

Musgrave – road – S – Musgrave Bridge – W – Little Musgrave – S past Smithfield – near

Scandal Beck – E over River Eden – road – SE on Daleholme Lane – Winton

Distance: 10 miles; Ascent: 70 metres

Home

Preamble

Index

Areas

References

Me

© John Self, 2018-

Top photo: The western Howgills from Dillicar;

Bottom photo: Blencathra from Great Mell Fell