The Wildlife of the Lune Region: A Beginner's Guide

The Wildlife of the Lune Region: A Beginner’s Guide describes a series of outings to explore the

wildlife of the region within the Lune catchment. The ‘beginner’ of the sub-title is me, not you.

A pdf version of The Wildlife of the Lune Region was placed on-line in 2016 but

has been replaced by this html version.

Contents

Introduction

Introduction

1. Curlews on Green Bell

2. Snails on Sunbiggin Moor

3. Orchids on Great Asby Scar

4. Trees in Edith’s Wood and Greta Wood

5. Cinnabar Caterpillars near Heysham Moss

6. Marsh Gentian on Keasden Moor

7. Small-Leaved Lime in Aughton Woods

8. Eels in the Wenning

9. Cattle on Fell End Clouds

10. Pink-Footed Geese in the Wyre-Lune Sanctuary

11. Purple Saxifrage on Ingleborough

12. Sand Martins by the Lune

13. Fell Ponies on Roundthwaite Common

14. Cuckoos in Littledale

15. Small Pearl-Bordered Fritillaries on Lawkland Moss

16. Kingfishers by Bull Beck

17. Himalayan-Balsam on the Upper Lune

18. Juniper on Moughton

19. Wolf-Spiders by the Lune

20. Hen-Harriers in Roeburndale

21. Sitka-Spruce in Dentdale

22. Dippers in Barbon Beck

23. Alpacas in Rawtheydale

24. Hares at Winmarleigh Moss

25. Lesser-Black-Backed-Gulls by Wolfhole Crag

26. Red-Deer in Wasdale

27. Buzzards at Wandale Hill

28. Ferns on Leck Fell

29. Yellow-Horned-Poppies at Middleton Sands

30. Badgers in Lawson’s Wood

31. Salmon in the Lune

32. White Stoats on Caton Moor

33. Rhododendron at Kitmere

34. Lapwings on Swarth Fell

35. Belted-Beauty-Moths at Sunderland Point

36. Bluebells on Middleton Fell

37. Swifts on Gragareth

38. White-Clawed-Crayfish and Red-Squirrels around the Upper Lune

39. Red-Grouse at Ward's Stone

40. Wrens in Our Garden

Introduction

The Wildlife of the Lune Region is a sort of sequel to

The Land of the Lune.

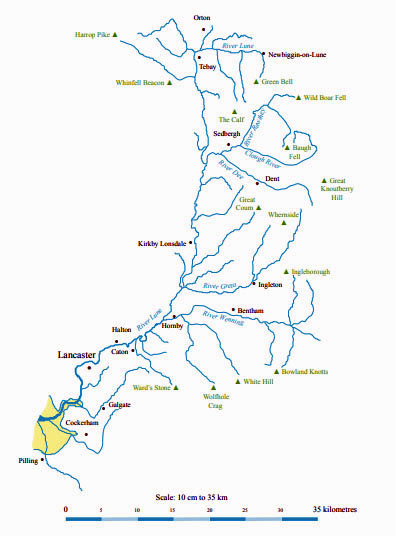

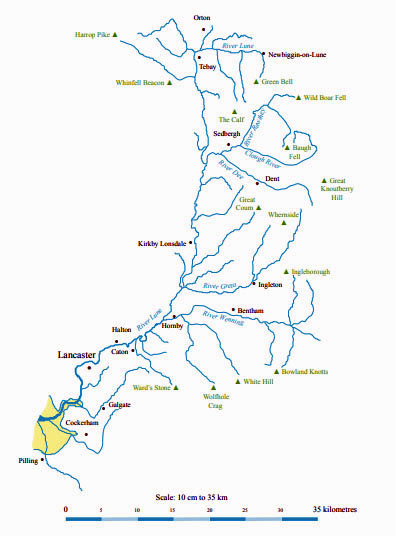

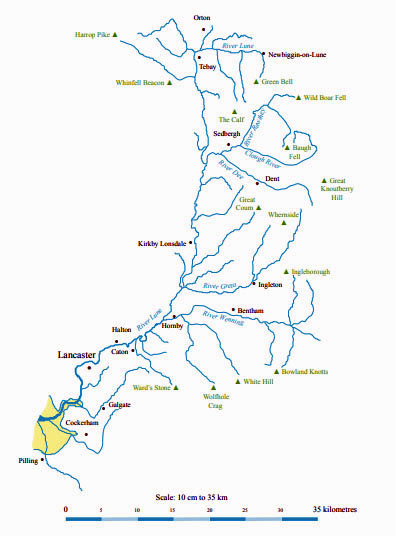

The Land of the Lune provided a general review of Loyne, which is

the shorthand I use for the region within the watershed of the River

Lune in northwest England (shown in the map below).

The Wildlife of the Lune Region is focussed more narrowly, as the

title says, upon the wildlife of this region. It is not concerned only

with the wildlife of the River Lune itself. It considers the wildlife of

the rivers, fells, moors, woodlands and valleys of the whole region

within the Lune catchment.

In The Land of the Lune I included topics that I found interesting,

in the hope that any reader would find some of them interesting

too. Consequently, the text flitted between the history, geology,

flora, fauna, people, buildings and so on of the region. This had the

virtue that if a reader was not interested in one particular kind of

topic then they could be assured that another kind would be along

very soon.

A reader of The Wildlife of the Lune Region has no such assurance.

If you are not interested in the flora and fauna of the region then,

apart from the occasional diversions, you will find little relief in

the following pages. However, if you consider yourself relatively

uninterested at the moment then perhaps you will persevere and

become more interested. I was not so interested myself until

recently. Like most people, I appreciated the wildlife that I saw but

did not think too much about it.

As a result of writing The Land of the Lune I became aware that

there were people who had spent a lifetime becoming expert in the

various topics that I glibly skated over. I felt a fraud writing about,

say, the bog bush cricket when I wouldn’t recognise one if it came

up and bit me.

I became involved in the activities of the Lune Rivers Trust, a

group of volunteers with the enthusiasm and expertise to oversee

the ecology of the Lune river system. I was humbled by the little

that my ignorance could contribute.

I therefore embarked upon The Wildlife of the Lune Region not

as an expert but as a newly-enthused amateur. This document is

a description of my attempt to find, understand and learn about

the local wildlife and the conservation issues that arise. It is not a

detailed, technical, academic description of that wildlife. It describes

a learning journey that I am happy to share with any other enthused

amateur that may wish to accompany me.

I began writing these words in 2013. I envisaged slotting the

words into the structure that had served me well in The Land of

the Lune, that is, one based upon an imaginary journey down the

River Lune, interrupted by journeys down its major tributaries. I

embarked upon a series of expeditions, starting at the headwaters of

the Lune, intending to write about the wildlife that I encountered.

However, I soon found that my expeditions should not be based

upon the details of the Lune river system. The seasons dictated

where I needed to be, in order to see what I hoped to see. Also, I

needed to tackle first those elements of the local wildlife that my

ignorance allowed me to.

So, in the winter of 2013 I re-organised the words into a more

straightforward, chronological narrative - or diary, if you will. I

dated those words according to the original expeditions. And

then I resumed the narrative in early 2014, aiming to write about a

suitable wildlife topic every once in a while.

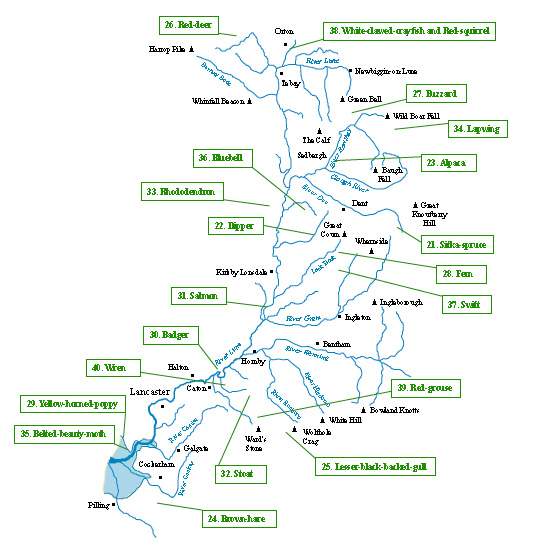

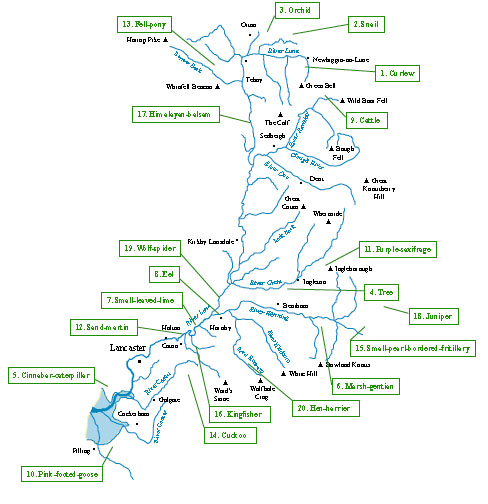

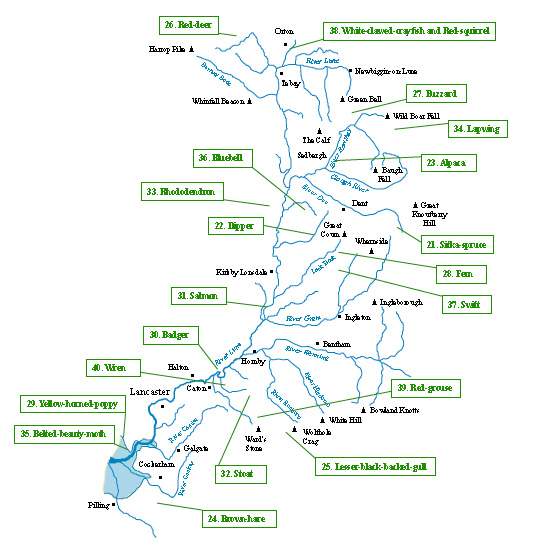

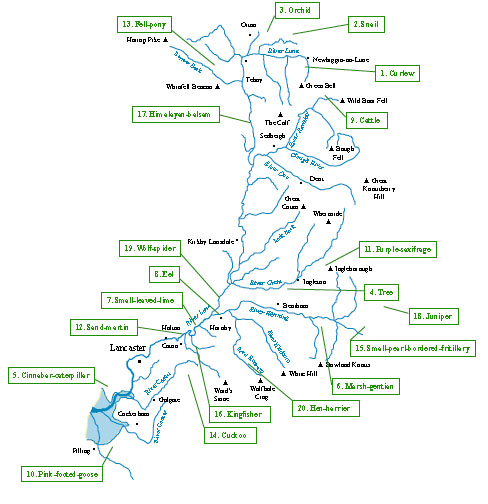

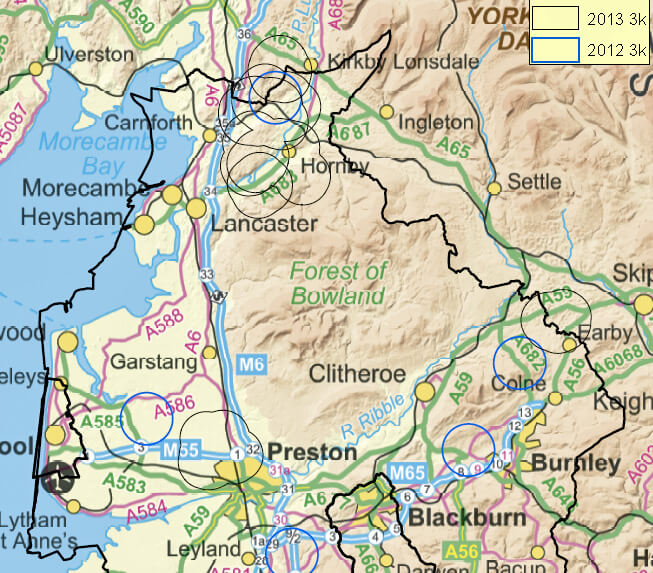

As a result, I hop, seemingly at random, around Loyne. Maps

after twenty sections and at the end of this document

may help you to determine where we are. If more information is

needed on the places themselves then I cannot do better than refer

you to The Land of the Lune!

As will be obvious, the comments and opinions expressed in

this document are mine alone. As always, if any reader has any

comments on or corrections to anything please let me know (at

johnselfdrakkar@gmail.com).

A Note on Pronouns

I hope that the switches between ‘I’ and ‘we’ are not too

disconcerting. The ‘we’ includes my wife Ruth, who joined in

on some expeditions (and encouraged me out of the house for

the others).

Photograph Acknowledgements

In The Land of the Lune I got away with amateur photographs

taken on an ordinary digital camera. The photographs were,

in fact, an afterthought. All that I had written before The Land

of the Lune were academic papers and books, where photographs

were a rarity. It was an eye-opener to me that the photographs in

The Land of the Lune impressed readers much more than the text. It

was also somewhat deflating, as many more hours of labour had

gone into the latter. Clearly the photographs created a reader’s first

impression - and, I suspect, in some cases the only impression.

Therefore in a document on wildlife I must include photographs.

Unfortunately, wildlife photography demands expertise and

equipment that I do not have. Fortunately, there are many fine

photographers keen to share their photos via on-line photo-sharing

systems such as Flickr.

I have in The Wildlife of the Lune Region liberally borrowed (or

stolen) from such sites. I hope that I haven’t violated the spirit of

these open access sites by including their photographs here. If any

photographer should come across any of their photographs here

and disapproves then I will gladly offer them a percentage of the

income from this free publication. If that is insufficient mollification

then I will offer my fullest apologies and remove the offending

photographs forthwith.

The captions of all stolen photographs refer to

the photographers, most of whom have excellent

portfolios of wildlife photographs that can be seen at the web

address indicated. I am very grateful to them all.

1. Curlews on Green Bell

April 2013

Right: The view from the source of the Lune on Green Bell

Right: The view from the source of the Lune on Green Bell

This was not a promising start. My search for the wildlife of

Loyne began with a view of a vast expanse of dull khaki-coloured moor-grass, enlivened only by the remnants of

recent snowdrifts. No trees, no shrubs, no rivers, no lakes. Nothing,

as far as I could see, but grass.

It was early April, with a bitter easterly blowing. I could hear

nothing but the wind. I stood at the source of the Lune, on the slopes

of Green Bell in the Howgills. Actually, because of the snowdrifts I

couldn’t locate the exact source. I stood in the first dribble of water

emerging from the snowdrift. Before me, I could trace the route of

the beck (Dale Gill), heading for Newbiggin-on-Lune, some three

miles away.

Beyond Newbiggin were the gentle slopes of Crosby Garrett

Fell. On the horizon the snow-covered but normally dark Pennine

hills stretched away from Appleby towards Penrith. Fifteen miles

distant, the bright snowball communication centre on Great Dun

Fell had been rendered inconspicuous.

I would not see much wildlife by looking fifteen miles away.

Looking down to my feet, I saw that I was in fact not standing on

dull moor-grass. I was paddling in a deep-green substance, some

kind of water-cress, perhaps. As I strode downhill, a dark bird,

a snipe perhaps, inconsiderately took flight before I could focus

upon it. In a gully, trying hard to restrain my excitement, I came

upon a small patch of heather and some bright green lichen on

exposed slate - topics that I will leave for another day. And, yes,

the beginnings of a tree, or at least, a shrub. And in the next gully

a veritable copse of trees.

Left: The first trees of Loyne

Left: The first trees of Loyne

If this is to be a worthwhile discussion of Loyne wildlife, I cannot

get away with ‘trees’. I need to be more specific. Unfortunately,

identifying trees without the help of foliage is a new challenge for

me. The dark slate-grey bark with horizontal markings leads me,

with the confidence of ignorance, bravely to assert that the first tree

in Loyne is a rowan.

As is immediately obvious, I am not a wildlife expert. I hope

to become less inexpert during the course of this journey. In the

meantime, I will rely upon the expertise of real and virtual friends

to put me right.

As I walked on past High

Greenside I heard a sound that

even I could not mistake: the

song of the curlew Numenius

arquata [1].

Two curlews glided

over the moor, with exquisite,

flowing notes, an exuberant

trill, yet with a touch of

melancholy.

They had returned to their

nesting haunts after wintering

in tidal waters, which is

quite a bold expedition to

have made already after this

protracted cold winter. They

nest in a scrape upon the

ground, producing young of

a surprising cuteness. The

chicks are mottled, to escape

observation, and have a short

beak that does not hint at the

curved 6-inches of the adult

curlew beak. The parents

tend to position themselves

between the chicks and an

approaching human, which

gives a good clue as to where

to spot the chicks. The parents

and young do not linger on the

moor once the latter are able to

make their way to the shore.

Right: A curlew chick (Andrew Martin)

Right: A curlew chick (Andrew Martin)

Far right: A curlew in flight (Thomas Heaton)

The curlew is Europe’s

largest wading bird, although there is not much for it to wade in

on this moor. It is some 55 centimetres in length and stands high

on long grey legs. It is, however, more familiar in flight, when its

evocative song draws the eye towards it. Sadly, its numbers are

declining sufficiently to make it an ‘Amber bird’ on the Green,

Amber and Red Lists.

These lists have been devised by the UK’s leading bird

conservation organisations.

In 2009 246 species were assessed

against a set of objective criteria to place each on one of three

lists – Green, Amber and Red – indicating an increasing level of

conservation concern. There are 68 species on the Green List,

126 on the Amber List and 52 on the Red List. Red is the highest

conservation priority, with species needing urgent action, with

Amber being the next most critical group.

Left: The Green Bell trig point, looking towards Randygill Top

Left: The Green Bell trig point, looking towards Randygill Top

Red List birds are defined to be globally threatened or suffering

from a severe (at least 50%) decline in UK breeding population

or breeding range over the last 25 years or a longer-term period.

Otherwise, if the species:

• has poor conservation status in Europe;

• or its population has declined during 1800–1995 but is now

recovering;

• or its UK breeding population or range or non-breeding

population has moderately declined (25-49%);

• or it is localised (most of its UK population is in 10 or fewer

sites);

• or it is a rare breeder (1–300 breeding pairs in the UK);

• or it is a rare non-breeder (less than 900 individuals);

• or it is internationally important (at least 20% of the European

population in the UK)

then it is on the Amber List. Species that occur regularly in the UK

but do not qualify under any of the above criteria are on the Green

List.

Since 2009 the curlew has continued to decline, so much so

that it seems to warrant transfer to the Red list. Its UK breeding

population declined by about 60% between 1970 and 2010,

including 44% just from 1995. Its alarming decline internationally

led to the announcement of an International Conservation Plan in

2013. It is now considered ‘globally near threatened’ by the IUCN

(International Union for Conservation of Nature).

However, officially, at the moment the curlew is an Amber bird,

which at least I now know does not mean that it is an amber bird.

My initial foray has helped me to realise that not all wildlife will

be as visible and as easily identifiable as the curlew. I will need to

curb my normal purposeful march through the countryside. I must

pause, look and listen. I will need binoculars and a magnifying

glass. I will need guidebooks to help me identify the birds, plants,

beetles, lichen, trees, and so on. I cannot rely on serendipity. I

will need to prepare my expeditions, to help me anticipate what to

look for and where. I should read all I can to help me understand

whatever I am able to see of the wildlife of Loyne.

So, with a slightly better appreciation of the task ahead of me, I

continue on my way.

[1]. I give the Latin scientific names in order to provide a veneer of

academicism (but only if I write a paragraph or more about the

species, otherwise the text will be cluttered with the things). I only

give the scientific name once, on the first significant mention of the

species.

[2]. http://www.rspb.org.uk/wildlife/birdguide/status_explained.aspx.

2. Snails on Sunbiggin Moor

June 2013

Right: Sunbiggin Tarn

Right: Sunbiggin Tarn

As the Lune heads west from Newbiggin-on-Lune towards

Tebay it passes to the south of limestone scars. Rais Beck

arises below Little Asby Scar and meanders via Rayseat

Sike and from Sunbiggin Tarn, occasionally disappearing through

the limestone, to reach the Lune near Raisgill Hall. The upland

tarn lies at 250m in a hollow between the scars and the Kelleth

Rigg ridge above the north bank of the Lune. The region around

Sunbiggin Tarn is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which

sounds promising.

What interests scientists may not interest me, so let me consult

its citation,

that is, the official reasons given for granting SSSI status

to Sunbiggin Moor.

There seem to be three main reasons.

First, as can be readily appreciated even by me, a variety of

habitats is to be found within this small region. The limestone

scars give rise to calcareous soil, that is, soil that contains calcium

carbonate and hence is relatively alkaline. Around Sunbiggin

Tarn, the wetlands and heather-dominated fen include areas of

acidic mire. Therefore flora and fauna characteristic of the different

habitats may be found unusually side-by-side.

Secondly, the habitat’s distinctive

natures support various rare species.

Specifically, according to the citation,

the area around the tarn is the

only location in the British Isles for

Geyer’s whorl snail Vertigo geyeri.

Local literature repeats this claim, as

indeed did I in The Land of the Lune.

However, I am doing my research

a little more thoroughly now and

I have read elsewhere that recent surveys

have recorded the snail at

thirty locations in the UK, including

two, possibly three, in England.

But it hasn’t been seen anywhere else in

Loyne, so if I want to see it, this is the

place to look.

So, on a bright June day, I set

off, intrepid explorer that I am,

undaunted by unforeseen dangers, from the watershed near Grange

Scar with the specific objective of finding Geyer’s whorl snail. I

knew exactly what it looks like, thanks to Wikipedia. And although

it is small (less than 2mm across) I am assured that there are plenty

of them. Surveys have found it to be the most abundant snail in the

region, forming about a quarter of those collected.

Left: Geyer’s whorl snail (Wikipedia)

Left: Geyer’s whorl snail (Wikipedia)

Geyer’s whorl snail is an air-breathing land snail. Surprisingly

(to me), some snails have lungs and others have gills, but both kinds

of snail can be found in water and on land. As it happens, Geyer’s

whorl snail has lungs, although I didn’t expect to see them.

The snail is a relic of post-glacial conditions. Since

then climate change has greatly reduced its range and it is now

vulnerable to changes in the hydrological conditions of its present

sites. So it was with some misgivings that I embarked upon my

search.

I was reminded of the dwarf caribou. This caribou may have

been dwarf but it was not as small as Geyer’s whorl snail. Anyway,

in the 1870s it was rumoured that a relic subspecies of caribou lived

in a remote Canadian swamp far from and dissimilar to the habitats

of other caribou.

Scientists were sceptical and a reward was offered to anyone

who brought a specimen of the elusive dwarf caribou. In due course,

a local Indian brought forth a skull fragment of such a caribou and

claimed his reward.

However, some scientists remained sceptical, suspecting that

the Indian had brought his caribou skull from the distant habitats.

So in 1908 a hunting party set out to settle the matter once and for

all. Eventually, they came upon a small herd of dwarf caribou, shot

them, and triumphantly brought them back to the satisfaction of

the scientific community.

It was indeed a rare species. No more dwarf caribou were ever

seen. Perhaps the existence of the dwarf caribou was confirmed at

the very instant that the extinction of the species was achieved [1].

The moral of this tale was

perhaps reinforced as I walked

past Spear Pots. The OS map

marks this as a lake. Now, it is

a small flat grassy area. I have

vague memories of this indeed

being a lake, surrounded by a

number of hides, whether to

watch or shoot the waterbirds,

I don’t know. Either way, the

waterbirds are no more, which

is perhaps why the lake is no

more.

I continued on to Tarn

Moor, around Sunbiggin Tarn.

I realised that, amateur that I

am, I had chosen a poor day to

search for snails. It had hardly

rained for weeks. The heather

was brittle dry. The ground was unusually dusty. Only by Tarn

Sike was there any of the wetness that is more normal for the moor.

If Geyer’s whorl snail is anything like my garden snails it would not

venture forth on such a desert.

In any case, I was concerned that my walking about on Tarn Moor

may upset the hydrology and hence the delicate snail. Geyer’s whorl

snail is fully protected, which should include protection against

my boots. Being a ‘fully protected’ species means that, under UK

legislation, it is an offence to disturb, kill or injure a member of that

species or to disturb their breeding and sheltering places. Standing

on a 2mm snail is, I should imagine, likely to disturb it somewhat.

So, after reflection, I didn’t, after all, worry too much about

the snail. To tell the truth, I am not very excited about snails. As

wildlife goes, snails are not very wild and nor do they go much.

My aborted search for the snail had its rewards, however.

There was a surprising luxuriousness in the vegetation on the

boggy banks of Tarn Sike. Amongst the dominant marsh marigold

various wildflowers flourished, including the attractive specimen

shown to the right.

After several hours perusing the wildflower catalogues, I am

now prepared to identify this as bogbean or buckbean Menyanthes

trifoliata. Botanists will shake their heads. How can anyone take

hours to identify a bogbean, with its distinctive white flowers, pink-tinged, fringed

with white hairs, and with rose-coloured buds? In

my excuse, the catalogues all insist that bogbean’s flowers have

five petals. All the drawings and photographs show this to be the

case. But my specimen had six petals. I was struck by its attractive

symmetry.

This is disconcerting. Are all flora so lax in following their

descriptions? Must I read the catalogues less literally? As children,

we search for four-leaved clovers among the common three-leaved

versions. So perhaps it is not so unusual for plants to have variations.

Perhaps, evolutionarily, it doesn’t matter much whether a plant has

five or six petals. At least, not as much as it would for, say, a dog to

have four or five legs.

It was then time to attend to the third main reason given in

that citation. This concerns the birdlife around Sunbiggin Tarn. It

is the largest body of water for several miles in any direction and

therefore a focus for many birds. The lake is, however, not large,

forming about six hectares of open water. It can be walked around

in an hour if you are prepared to climb various fences and walls

designed to prevent sheep (or you) wandering into the reeds that

surrounds the tarn and its neighbour, Cow Dub.

The citation mentions twenty-two species of bird to be seen at

the lake, from, in alphabetical order, black-headed gull to wigeon.

Unfortunately, the birds do not have the courtesy to all turn up at

the same time. On any particular visit, only a subset will be seen.

My June visit yielded two swans, two moorhen, several gulls, with

curlew and skylark heard overhead, one snipe disturbed while I

circumnavigated the tarn, and a buzzard hovering nearby.

However, I trust the citation (except for the black-headed gulls,

which I have read elsewhere have recently deserted Sunbiggin

Tarn). The surrounding wetlands look fine breeding ground for

waterfowl, with the reed marshes providing a degree of protection.

The moorlands, relatively unfrequented by humans, are surely

nested upon by skylark, snipe, curlew and lapwing. Ornithologists

with the time to come repeatedly in order to survey passing birds,

especially those on their winter migration, are no doubt rewarded

by the sight of many species for whom Sunbiggin Tarn forms a

welcome resting place.

As indeed it does for me.

[1]. The tale of the dwarf caribou is given, with details of other extinction

events, in David Day (1990), Noah’s Choice, London: Puffin Books.

3. Orchids on Great Asby Scar

June 2013

Left: Great Asby Scar

Left: Great Asby Scar

The western end of the limestone ridge that begins above

Sunbiggin Tarn drains via Chapel Beck through and by Orton

to the Lune north of Old Tebay. The scars that lie south of the

wall that runs from Knott to Little Kinmond form part of the Great

Asby Scar Nature Reserve, most of which lies north of the wall and

drains to the Eden. Well, a nature reserve should be of interest, so

I decided to have a look.

Right: Looking towards Orton from Great Asby Scar

Right: Looking towards Orton from Great Asby Scar

The limestone has been significantly weathered since the last

Ice Age (of 10,000 years ago). Vertical weaknesses in the limestone

have been eroded to form deep fissures (called grikes) and many

loose fragments lie upon the limestone blocks (called clints) between

the fissures. These so-called pavements are more hazardous to

walk upon than any pavement which we might harangue the local

council about.

Nonetheless, it is my duty to investigate the exceptional flora

found around the pavements. Unfortunately, the specimens that

are of most interest (to experts) are to be found lurking within the

grikes, where the shelter, rainwater, and protection from sheep

enables various uncommon plants to flourish.

My enthusiasm does not yet drive me to spend the day on my

knees peering into gloomy grikes. I accept what the experts tell

me - that within these grikes are to be found woodland plants such

as wood anemone and dog’s mercury and herbs such as angular

solomon’s seal and bloody cranesbill. At the moment, I would not

recognise these even if I saw them (at least, not without a wildflower

book to hand).

There are also many varieties of fern (rigid buckler-fern, brittle

bladder-fern, hard shield-fern, lady-fern, and so on). To my eye,

the ferns all look much the same, with the green fronds (which I am

delighted to discover is not only my word but the correct botanical

name for the leaves of ferns) hidden and occasionally protruding

from the grikes.

Even more occasionally, something more substantial had

managed to grow and emerge from the grikes - trees. Most are

somewhat stunted although on Little Kinmond there are relatively

well-developed hawthorn, ash, rowan and sycamore. Overall,

though, the limestone pavements presented an apparently desolate

and barren scene.

The main problem for any flora is not so much the exposure

to the elements but the effects of grazing by sheep and cattle. For

example, the fact that the large sycamore - I found only one - stands

alone is testament to the efforts of sheep and cattle around it.

Recently, grazing on the scars has been reduced to enable the flora

to recover, although they are still relatively denuded of flowers.

Undeterred I set out to look for flowers on the pavements.

Passing over the usual daisies, buttercups and dandelions, the first

flower that I alighted upon was an unexpected but familiar friend,

the bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta. I thought the bluebell was a

flower of, or near by, woodland. I would not have expected it to

flourish on these exposed rocks at 350m. Clearly, the shallower

grikes provide enough protection and nourishment.

Left: Bluebell on Great Asby Scar

Left: Bluebell on Great Asby Scar

Right: Early-purple orchid

The most prominent flower on the limestone grassland,

however, was an orchid, which since it was early in the season and

its flowers were deep purple,

I confidently identify as an

early-purple orchid Orchis

mascula.

I felt I ought to check this

in the catalogue. I found that

the early-purple orchid is

our commonest orchid and is

often seen with the bluebell, so

that’s promising. However, I

also found that there are about

25,000 species of orchid - four

times as many as there are

mammals. Moreover, they

cross-breed to produce 100,000

or so hybrids. A thorough

search through the catalogue

would take me some time.

However, I was distracted

by the discovery that the

name ‘orchid’ comes from the

Greek for ‘testicle’. The root

is so shaped, apparently. In

Greek mythology, the gods

transformed Orchis, the son

of a nymph, into a flower after

he tried to rape a priestess

of Dionysus. After this

unpromising start, orchids

have become the jewels of the

plant world. Actually, the real

start for orchids was, according

to fossil evidence, before the

dinosaurs became extinct.

So, orchids are a venerable

species. Today, enthusiastic

fans will pay fortunes for rare

specimens and tropical orchid-hunting had almost the romance of

the first jungle explorations.

As can be imagined, with so many species, orchid flowers

vary greatly. However, I must not despair for there are only fifty

or so native British species. Their flowers are usually purple-ish,

mottled with white or green, and bear their flowers in single spikes

or clusters. One can therefore usually confidently identify a plant

as an orchid, although maybe not which one.

There were also flowers around the Great Asby Scar pavements

that were not orchids. But I did not worry about those because, with

bluebell and orchid, I already felt that I’d done rather better than

Alan Coren, who wrote that “This evening, my son and I embarked

upon a pleasant excursion to collect examples of the wild flowers

with which this part of the forest is so abundantly blessed. We

collected a daisy, and fifty-nine things that weren’t” [1].

[1]. Alan Coren (June 6, 1979), The unnatural history of Selbourne, Punch.

4. Trees in Edith's Wood and Greta Wood

July 2013

Orchids in their thousands, bogbeans with the wrong number

of petals, 2mm snails - this wildlife game is quite tricky,

isn’t it? I felt a need to retreat to safer ground. I decided to

have a look at trees. Even I know a tree when I see one.

I started with a wood especially planted for people like me -

Edith’s Wood, near Ingleton. This was newly planted in 2002 with

native trees (so I won’t be confused by pesky foreign trees or strange

hybrids). I refrained from reading which ones, to give myself a

challenge.

Left: Ingleborough from Edith’s Wood

Left: Ingleborough from Edith’s Wood

However, I needed to do some preparatory reading to get a grip

on trees. Alas, I soon found that a ‘tree’ is not precisely defined. It

is not part of the scientific classification system for plants. Neither

is ‘bush’ or ‘shrub’. But everyone has a commonsense idea of what

a tree is, so I’ll leave it at that. I needed to break trees down into

more manageable groups and classes, so that I may more easily

identify them and appreciate their characteristics. Unfortunately,

almost every grouping that is suggested seems to be hedged with

various qualifications and exceptions.

A starting point might be that trees can be divided into those that

have seeds that are not contained in anything (the gymnosperms)

and those that have seeds that are contained in something (the

angiosperms). The former correspond to evergreen, softwood

conifers such as pine and fir; the latter to deciduous, hardwood

broad-leaved trees such as oak and beech. Except that: some of

the former lose their leaves in winter (for example, larch) or are

hard-wooded (for example, yew) and some of the latter do not lose

their leaves in winter (for example, holly) or are soft-wooded (for

example, willow).

Also, an evergreen tree is not necessarily very green (for

example, Colorado blue spruce); the ‘hardness’ of wood is a

subjective judgment that I cannot make unless I take a saw with me

on my walks; the leaves of broad-leaved trees do not always seem

very broad to me.

Botanists classify trees as they do other members of the Plantae

‘kingdom’. First of all, trees are grouped into families, such

as Fagaceae (informally, the beech family) or Sapindaceae (the

soapberry family). The members of each family have the properties

that define that family. These definitions involve the use of botanical

terminology that it is beyond my competence and your patience to

explain.

Each family contains one or more genera, such as Quercus of

Fagaceae (informally, the oak genus) or Acer of Sapindaceae (the

maple genus). Of course, not all genera have familiar informal

names like oak or maple.

Then each genus has one or more species, such as Quercus robur

(English oak) or Quercus rubra (red oak) or Acer pseudoplatanus

(sycamore) or Acer negundo (box elder). Sometimes, a species exists

in variations distinct enough to warrant an extra suffix, such as

Populus nigra ‘Italica’ (Lombardy poplar), a variant of Populus nigra

(black poplar), a species within the Populus (or poplar) genus of the

Salicaceae (or willow) family.

So, now I can give a proper name to a tree, if I can but determine

what name it should be. As far as I am concerned, the identification

of a tree has to be based on what I can see - its overall form, its

leaves (if any), its trunk and bark - bearing in mind that all these

are liable to vary according to the season, the location and the age

of the tree.

I started off with the most basic guide I could find. In all of

fifteen pages (seven of which were illustrations) it provided advice

on identifying about a hundred trees. First, I must place the leaf

shape into one of ten categories. To help me, a little drawing

was provided. Nobody is a complete novice at this game and I

might imagine that I could think of an exemplar for each of the ten

shapes:

ace-of-spades - silver birch

elliptical - sweet chestnut

jagged - oak

long and narrow - willow

needle - spruce

oval or pointed oval - beech

palmate (like fingers) - horse chestnut

palmately lobed - sycamore

pinnate (having two rows of leaflets) - ash

rounded - hazel

This is, of course, rather superficial. For a start, there are several

oaks and willows. I really ought to give the species name to be

clear. But my hope is that if I can say that a particular leaf is a bit

like what I think of as, say, an oak then that will narrow down my

search to, on average, ten or so trees in my little handbook.

Then I can compare my leaf with the drawings and check my

tree against the brief descriptions. For example, if I find a beech-like leaf (that is, an oval one) and see that the tree has “bark smooth,

grey; twigs slightly downy”, then I might have a stab at hornbeam

Carpinus betulus.

Thus emboldened, I set forth into Edith’s Wood. Proceeding

from the southern corner, I immediately realised a difficulty. The

trees had not grown that much in eleven years or so and may not

have the mature properties described in my little book. Typically,

the bark of a tree goes through various states as a tree ages (much

like our skin, I suppose) and in its youth a tree may not have the

characteristic overall form of its maturity.

Still, I was confident that I first encountered oak, probably

Quercus robur, and ash Fraxinus excelsior. Then, in the next set, hazel

Corylus avellana and hawthorn Crataegus monogyna. Somehow, the

species names made the achievement more commendable.

As I was closely studying a rose in the hope of pinning down

its species name, a young deer wandered up nearby, also taking a

keen interest in the low-lying leaves, but with a different purpose

to me. It took little notice of me. Perhaps it was unfamiliar with

the human species, as there was little sign that it frequented Edith’s

Wood regularly. A dog rose Rosa canina, I think.

And so on, slowly through the seven hectares or so ... birch Betula

pendula (some looking a little poorly, the only trees that seemed to

be struggling), alder Alnus glutinosa, and ... what’s this? So far, I

think I might, even without my little book, have had a general idea

of all the trees so far but this one was different.

I had already realised

that it is harder than it might

seem to place a leaf into one

of ten shapes - some of them

are rather similar and leaves

are rather variable. After due

deliberation, ... leaves lobed

(a bit like a sycamore), five

lobes, could be a maple, “red

when young” ... yes, I opted

for field maple Acer campestre.

I didn’t have a judge to

give confirmation but I was

convinced. Joy unconfined! I

had managed to identify a tree

that I am not sure that I’d even

heard of before. Or is a field

maple what is often just called a maple? (Not that I could identify

a maple.)

Left: The young tree (field maple?) in Edith’s Wood

Left: The young tree (field maple?) in Edith’s Wood

I am developing a fresh appreciation of the expertise of

arboriculturists and silviculturists who can effortlessly identify

hundreds of species of trees and immediately recall their distinctive

properties. I also see the need for these fancy scientific names. I

think I was vaguely aware that a rowan or mountain ash was not

really a kind of ash (although the leaves are certainly similar). Now

I read that the former is Sorbus aucuparia and therefore of the rose

family and the latter is Fraxinus excelsior of the olive family. Who

would have thought it?

Now enthused, I headed for the Woodland Trust’s Greta Wood,

near Burton-in-Lonsdale. This, I saw straightaway, presented a

different challenge. As I entered the wood on the footpath from

Burton Bridge, I walked under a dense canopy of mature trees.

Indeed, they are so mature that the wood has been designated an

Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland (ASNW). An ‘ancient’ wood is

defined to be one that has

existed continuously since

1600, before which date trees

were not commonly planted.

Therefore, an ancient wood

is likely to have developed

naturally.

Right: Beech in Greta Wood

Right: Beech in Greta Wood

However, the word semi-natural, suggests that the wood

may not be entirely natural

now. As I walked through

the gloomy wood, I found a

majestic stand of old beeches

at the western end, along with

many ash and a few oak, but

the overwhelming impression

was of sycamore. These cast a

dark shadow over everything.

I can see enough sycamores

from my garden. It was a

disappointment to see so many here. It seems that many experts

share my lack of enthusiasm for sycamore.

To the layman, sycamore is a familiar, natural tree. It is, in fact,

native to central Europe and is thought to have been introduced

here in the 16th century. It is therefore, strictly speaking, a non-native tree, although fully ‘naturalised’, that is, capable of persisting

as a self-sustaining population.

Sycamore disperses its fruit through its characteristic

‘helicopters’. This is does rather too well, for the seeds are widely

distributed and grow vigorously under moderate shade. The

seedlings do less well under the sycamore’s own dense shade. As

a result, sycamore often grows in a kind of partnership with other

species, such as ash, which can grow under sycamore and under

which sycamore can grow [1].

Left: Sycamore by Greta Wood

Left: Sycamore by Greta Wood

Clearing sycamore can be counter-productive because it may

well be the first tree to re-colonise the cleared land. Sycamore will

appear to take over clear land, as an invasive species, until its own

presence stifles further growth. Because of its apparent invasive

properties (and perhaps lingering resentment for it being alien),

sycamore is regarded as a threat to native wildlife. Conservationists

therefore advocate its removal, especially from ancient woodland.

This policy has not, it appears, been applied to Greta Wood.

A Natural England report includes sycamore in a list of 21

species (out of 2,700 non-native species considered) that have

“demonstrated major negative environmental effects” [2].

Sycamore is allegedly a “competitor; aesthetically bad”.

I am no defender of sycamore but that judgement seems

debatable. The aesthetics of sycamore are a matter of opinion. It

cannot look so bad otherwise it would never have been planted in

such numbers to decorate city roads. As regards being a competitor,

sycamore seems to grow in partnership with other species, as

indicated above. The overwhelming dark canopy is not good for

its undergrowth but it doesn’t exactly compete with it.

I cannot say if Greta Wood would be better if the sycamore were

removed. I can say that I was relieved to escape from its gloominess

onto the open footpath that continues along the south bank of the

River Greta.

Here, in a narrow strip of

woodland by the riverside,

trees present themselves

separately, in an orderly

fashion, which it is a pleasure

to inspect and try to identify,

one-by-one. Alder, oak,

hawthorn, holly, hazel, spruce

... but, once away from Greta

Wood, not a single sycamore,

as far as I noticed.

It is a mystery to me that

sycamore can flourish in,

indeed dominate, a dense

wood like Greta Wood, one

which is no doubt under the

careful management of the

Woodland Trust, but, despite

being regarded as an invasive

species, cannot reach far out

here, into the open, by the

riverside, onto land that is not

managed (as far as I know).

Perhaps sycamore is not such a bad tree, after all.

[1]. Mike Townsend (2008), Sycamore - Acer pseudoplatanus,

Woodland Trust report.

[2]. Natural England Research Report No. 662 (2005),

Audit of non-native species in England.

5. Cinnabar Caterpillars near Heysham Moss

July 2013

Left and Right: Heysham Moss

Left and Right: Heysham Moss

In April 2013 the local paper reported that “A huge wildfire ripped

through the [Heysham Moss] reserve destroying everything

in its wake at teatime last Friday” [1].

Perhaps only in Loyne do

disasters happen at teatime. The report continued: “A raised bog

... was devastated during the fierce blaze. It could be years before

the vegetation and wildlife regenerate themselves, according to a

Lancashire Wildlife Trust spokesman”. I thought that I’d have a

look at the devastated reserve, and then revisit after a couple of

years to see how the regeneration was progressing.

The Wildlife Trust Nature Reserve of Heysham Moss is on the

western edge of the flat region bisected by the A683 from Lancaster

to Heysham. This region lies west of the Lune, between the small

ridge that peaks at Colloway Hill (36m) and the village of Heysham

itself. The fields are drained by many ditches that yield fine

agricultural land for cattle and sheep. In the past, however, this was

a vast waterlogged morass, no doubt occasionally inundated by the

sea. A century or two ago this region was called Little Fylde.

A remnant of the past can be seen at the lowland bog of Heysham

Moss. It is at an altitude of about 10m and you can’t get much lower

than that. According to the information board at the site, 3m of that

10m is peat laid down in the last 4,000 years.

Lowland raised bogs once covered much of Lancashire’s coastal

plain but they have almost all been reclaimed for agricultural use.

Heysham Moss itself is not entirely intact, with drainage and peat-cutting having occurred

at the periphery, but the central area is

relatively pristine. Here, purple moor-grass and common cotton-grass dominate. There are also

characteristic bog plants such as

bog myrtle, bog asphodel and round-leaved sundew and many

varieties of sphagnum moss.

Left: A ditch in Little Fylde (with ducklings)

Left: A ditch in Little Fylde (with ducklings)

I did not go directly to Heysham Moss but walked to it across

the reclaimed agricultural land. I wanted to imagine how different

this activity would be if it were all still like Heysham Moss. I walked

along the surprisingly tranquil footpath from White Lund. Once

away from the road, there was not a sound except the twittering of

swallows. Along the track I found ragwort Senecio jacobaea festooned

with caterpillars of the cinnabar moth Tyria jacobaeae.

Ragwort is poisonous to

horses and livestock, although

they know to avoid it. In the

summer its yellow flowers

dominate road-sides. Its

notoriety as a weed led to

the distinction of having a

government bill named in

its honour, the 2003 Ragwort

Control Bill.

During the drafting of

the bill it was pointed out

that about thirty invertebrate

species are entirely dependent

on ragwort, and ten of these

are considered scarce or rare.

The bill therefore backed off

from proposing the eradication

of ragwort, merely suggesting

that its spread be controlled

where it might form a hazard

to grazing animals.

Right: Cinnabar moth caterpillars on ragwort

Right: Cinnabar moth caterpillars on ragwort

Far right: Cinnabar moth (Alison Day)

One of the species

dependent on ragwort is

the cinnabar moth. It is still

a common moth although

its numbers have dropped

considerably following the

attempts to control ragwort.

The moth is a striking black

and red (cinnabar-coloured,

indeed) and its caterpillars are

equally eye-catching, being

striped black and yellow. This

helps warn predators to steer

clear of the poison that the

caterpillars have ingested.

The female moths lay eggs in batches of fifty or so on the

underside of ragwort leaves. Numerous caterpillars on one

ragwort plant soon reduce it to a bare stem, as was underway on

my observation. So voracious are they that they have been used to

control ragwort.

This is a microscopic illustration of the complexities faced by

our attempts to control nature. The fact that ragwort is poisonous

to valuable animals has helped persuade us that it is a weed that

should be eliminated. In fact, the plant itself is a perfectly reasonable

specimen and it is not excessively invasive. The cinnabar moth and

its caterpillars are attractive examples of their kind and it would, of

course, be a shame to lose them.

I eventually reached Heysham Moss and completed the walk

around the perimeter path. I noted impressively high purple

moor-grass and scrubby birch and willow woodland. It had been

exceptionally dry in the preceding weeks and the whole area

looked parched, which I am sure is far from its normal state. But

I didn’t notice any real sign of the fire. Either the local paper was

exaggerating or the reserve had already recovered remarkably.

The most lasting impression, however, was of bracken, brambles

and clegs (or horse-flies). I am doing my best to love wildlife in all

its forms but the cleg defeats me. Would the world be so much

worse if Noah had forgotten to invite clegs onto his ark? I can find

no mitigating feature that overcomes its habit of settling unnoticed

on my arm, sucking my blood, until, too late, I feel the sting and

swat it away.

In the circumstances, I may forego the planned return trip to

the moss.

[1]. The Visitor (April 10, 2013), Beauty spot devastated by massive blaze.

6. Marsh Gentian on Keasden Moor

August 2013

Left: Marsh gentian (Tim Melling)

Left: Marsh gentian (Tim Melling)

As Keasden Beck runs from the expanses of Great Harlow

and Burn Moor it passes, just north of Turnerford Bridge,

a small undistinguished moor that has been designated

the Keasden Moor SSSI. The first sentence of its citation states that

“Keasden Moor is of special interest as the only known site for the

marsh gentian Gentiana pneumonanthe in the Yorkshire Dales”.

This statement is contentious on two counts: first, Keasden Moor is not

in the Yorkshire Dales and secondly, there are no marsh gentians

there.

The first is obviously so, from

looking at a map. The second is

open to contradiction by anyone

who succeeds in finding marsh

gentian on the moor.

The latest Natural England

review of the site (26th September

2012) admitted that “no marsh

gentian were seen”. The 4cm

bright blue, trumpet-shaped

flowers surely cannot be missed -

but perhaps 26th September is a bit

too late in the year to see them.

So I set off in August, with

some optimism, to carry out a

systematic search of the moor. I

marched up and down the moor

carefully surveying narrow strips

as I went. It is a small enough

moor to be thoroughly traversed

in two or three hours.

Unfortunately, I saw no marsh gentians. Not seeing is not

believing. Notwithstanding the SSSI citation, I will not believe that

there are any marsh gentians on this moor until someone directs me

to their exact location. I do not intend to search this dreary moor

again.

Marsh gentian is a nationally rare species - and, it seems, perhaps

rarer than it was thought. If it were to exist on Keasden Moor this

would be at the northern edge of its range in England. It is now

believed to survive at only a handful of sites in northern England.

Right: The ‘pond’ on Keasden Moor

Far right: Sneezewort

Is there a mechanism for de-registering a SSSI? There surely

ought to be in case the main reason for establishing a SSSI

disappears. Apart from the (non-existent) marsh gentian there is

little to commend Keasden Moor.

The citation, which is the shortest I have seen, also mentions

“a small pond [which] provides an additional feature of interest”.

This pond is said to be surrounded by various rushes with common

marsh-bedstraw, marsh willowherb, sneezewort and lesser

skullcap.

I can vouch for the rushes but I have to take the scientists’ word

for the rest. The pond is protected by a squelchy quagmire of a

depth that I had no wish to investigate. If the scientists have in fact

reached the pond itself I admire their bravery in the course of their

scientific duty.

Of the plants mentioned the only one that I found was sneezewort,

which is common on the moor itself, not just by the pond. I did

disturb a few ducks from the pond, their alarm suggesting that they

are rarely visited by humans. Nearby, I flushed out a snipe and

elsewhere on the moor a hare was startled into action.

Overall, then, this small moor forms a haven for wildlife, safe

in the knowledge that most humans have the sense not to walk

upon it. If it does not deserve to be a SSSI then perhaps it is better

regarded as a ‘nature reserve’ although I am unsure of the precise

legal difference between the two. In any case, it is not entirely

natural because sheep and cattle trample upon it. Perhaps they eat

marsh gentian?

7. Small-Leaved Lime in Aughton Woods

September 2013

Right: Aughton Woods, Lune, Ingleborough and hot air balloon

Right: Aughton Woods, Lune, Ingleborough and hot air balloon

Inspired by my foray into Edith’s Wood and Greta Wood and

now informed by two voluminous tree guides subsequently

acquired, I aimed to investigate Aughton Woods. I have walked

in these woods dozens of times and although I appreciated that the

trees were there I had never really taken much notice of them.

This woodland comprises Sidebank Wood, Cole Wood, Burton

Wood, Lawson’s Wood, Walks Wood and Applehouse Wood.

Different subsets of these woods form a Biological Heritage Site,

the Aughton Woods Nature Reserve (owned by the Lancashire

Wildlife Trust) and the Burton Wood SSSI.

The ancient name of Aughton is said to mean ‘oak-town’, which

indicates that these woods are of some vintage. Apart from oak,

there are other native species such as hazel, ash, wych elm, rowan,

hawthorn, fir, cherry and alder. The non-native sycamore and larch

is gradually being cleared. That is all well and good. These are all

old familiar friends - friends with whom I have recently become

closer. But pride of place in the literature on Aughton Woods goes

to the small-leaved lime. Now they’re talking! I like to search (if

unsuccessfully) for something new and rare on my outings.

The limes are Britain’s most noble trees. They are our tallest

broad-leaved trees, with attractive heart-shaped leaves. They grace

many parks, public gardens and palaces, such as Hampton Court.

Lime wood is fine-grained and doesn’t warp, making it suitable for

wood carvings and to make musical instruments. They are hardy

trees that provide good shade and will stand severe pruning and, as

a result, are often used in street avenues. Limes used to be thought

holy trees, able to provide protection against evil.

Right: The leaves of small-leaved lime

Right: The leaves of small-leaved lime

The leaves of the small-leaved lime Tilia cordata are, to my great

relief, smaller (4 - 7.5 cm) than the leaves of the large-leaved lime

Tilia platyphyllos (6 - 15 cm). The leaves of the medium-leaved lime

- no, it’s not really called that - that is, the common lime Tilia x

europaea are between the two (5 - 10 cm). Which is as it should be,

because the common lime is a natural hybrid of the small-leaved

lime and the large-leaved lime.

So if I found a heart-shaped leaf 7 cm long it could be off any

of them. However, if I measured all the leaves on one tree and

none of them exceeded 7.5

cm then perhaps I’d be safe

in identifying it is as a small-leaved lime.

Actually, if I found any

kind of lime in Aughton

Woods it ought to be the small-leaved species. This is because

Aughton Woods is supposed

to host native trees and the

common lime and large-leaved

lime are not native to this part

of Britain. The small-leaved

lime is relatively uncommon and is near the northern limits of its

range in Aughton Woods.

A careful study of the descriptions of the three species reveals

differences other than just the size of the leaves - that is, in the

precise shape of the heart, the hairiness and shininess of the leaves,

the overall shape of the tree, the appearance of the bark, the shape

and colour of the flowers, and so on. These, however, are, for

an amateur like me, subsidiary features to be used to confirm a

provisional identification. My first objective, as I set off for Aughton

Woods, was to find a tree with heart-shaped leaves.

... And, yes, there was little difficulty in finding small-leaved

lime, once I had overcome my preconception that a small-leaved

lime is a small tree. It is in fact among the largest trees in Aughton

Woods. The distinctive leaves are therefore far aloft, out of reach of

my ruler but they look small to me. Some of the trees have lower

offshoots, allowing a closer inspection.

The leaves may be confused only with those of hazel, but that of

course is more of a multi-stemmed shrub, not at all like the sturdy-trunked lime.

Hazel leaves are less heart-shaped and have more

ragged edges.

Small-leaved lime may be located without leaving the Lune

Valley Ramble path in Lawson’s Wood. There are a couple of

specimens by the field as you enter the wood from the east. In the

wood there is a series of eight footbridges over small gullies. If

you pause on the first five of these you can see a small-leaved lime

growing conveniently within a few yards of the footbridge. It is

almost as if the limes were planted in order to be viewed from the

bridges, but of course that is not the case as the bridges are recent.

I was overcome with a peculiar sense of achievement in finding

something ’new’ in a wood that I thought I knew well.

8. Eels in the Wenning

September 2013

Left: The weir at Hornby

Left: The weir at Hornby

The River Wenning curves below Hornby Castle to drop over

an arc-shaped weir. This weir, unlike most weirs in Loyne,

was not built for an old mill. Perhaps it was built to create

deep still waters above the weir to enable castle residents to fish and

boat. Perhaps it was intended to enhance the aesthetically pleasing

view of the castle from the bridge.

The weir’s symmetry is not spoilt by the presence of a fish

pass. Fish have to leap the weir. However, the north side of the

arc is broken by a green structure, the purpose of which is not

immediately obvious.

I once sat by Hornby Bridge to watch a heron swallow an eel

(more precisely, a European eel Anguilla anguilla). The heron has a

long neck but it is not as long as this eel was. It took the heron some

time to get the whole eel inside.

Herons are often to be seen standing by the weir. They have their

eye on fish that are waiting below the weir for the right conditions

to leap it and also on eel that, of course, cannot leap at all. For an eel

to move upstream it must leave the water, wriggle across land, and

re-enter above the weir. At

least, it would have before the

green structure was provided

to help eels past the weir. It

is, however, not intended for

eels as large as the one I saw

eaten. It is for small eels that

are supposed to wriggle up

through the green bristles.

Right: The Hornby eel pass

Right: The Hornby eel pass

The eel pass looks quite a

challenge. First, the eel has to

locate it. I imagine that small

eels travel up in the calmer

waters at the river’s edge rather

than battle along midstream.

So maybe half the eels are on

the wrong side for the pass

(maybe more, as I picture them coming on the inside bend from the

Lune). How do they know to struggle over to the other side? Once

there, they have two vertical walls to climb. It is much the same, or

worse, for all the other weirs and dams they encounter.

Considering what the eel has gone through to get to Hornby

weir, this seems a lot to ask. The eel has an implausibly complicated

life cycle. It holds the record for the number of names it has for its

various life stages.

Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea. If you search a map of the

100,000,000 square kilometres of the Atlantic Ocean you will find

only one sea, the Sargasso Sea to the east of the West Indies. So this

region of the ocean must be special.

Columbus and other sailors noticed an unusually calm region

of the Atlantic Ocean within which floated large masses of seaweed

(sargasso is a kind of seaweed). We now know that the Sargasso

Sea is bounded by four major currents: the North Atlantic Current

(to the north), the Canary Current (to the east), the North Atlantic

Equatorial Current (to the south), and the Gulf Stream (to the west).

These currents deposit debris within the 3,000,000 square kilometres

of the Sargasso Sea.

In order to learn about the Sargasso Sea, I have carefully read

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys, a book that is always near the top

of any list of best books. I found, however, that the Sargasso Sea is

only mentioned once (in the title). The book is deep and mysterious,

difficult to navigate, midway between the cross-currents of West

Indian and British culture and with its narrative threads somewhat

entangled.

Whatever the properties of the Sargasso Sea are, eels are

irresistibly attracted to them. They travel 6,500 kilometres from our

rivers to the Sargasso Sea in order to spawn and die. The larvae

(about 5mm long) are then swept by the Gulf Stream towards

Europe. Salmon live mainly in the sea and return to our rivers to

breed; eels live mainly in our rivers and return to the sea to breed.

So, the young eels are not seeking a specific ‘home’. Where they end

up in Europe is, I suppose, just where the ocean currents happen to

take them.

On their way across the Atlantic they grow to about 6cm and

become transparent. These ‘glass eels’ arrive at our estuaries in

spring. In freshwater the glass eel metamorphoses into a young

eel or ‘elver’. It was these eels that were consumed in spring-time

‘eel-feasts’, from which the word elver is thought to derive. They

then wander about our estuaries, rivers and lakes for several years,

growing to become ‘yellow eels’ of up to 80cm. When they become

mature ‘silver eels’, after 15 years or more, they descend our rivers

to cross the Atlantic back to the Sargasso Sea.

Right: Heron by the eel pass on Hornby weir

Right: Heron by the eel pass on Hornby weir

This is obviously a hazardous life. The Atlantic currents may

not gather the Sargasso Sea nutrients that eel larvae need. The Gulf

Stream may not bring the glass eels to our shores. Climate change

may be causing it to slow. No doubt there are predators galore in

the Atlantic that have adapted to the supply of food that has flowed

reliably for millennia.

If the glass eel reaches our shores, it faces pollution and all

sorts of barrier to its movement up our rivers. Within our rivers, it

faces our eel fishery industry, the most valuable commercial inland

fishery in England, according to the Environment Agency. If they

survive all that they have to try to travel all the way back to the

Sargasso Sea. And all the while the herons wait by Hornby weir.

It is probably no surprise, therefore, that the number of eels

in British rivers has declined - by more than 90% since 1970. The

European eel is now considered a ‘Critically Endangered’ species

by the IUCN. Critically Endangered is the highest risk category

and is used for those species that are facing an extremely high risk

of extinction in the wild.

In 2007 the European Union required all member states to

develop Eel Management Plans, the aim of which was to ensure

that the number of silver eels returning to the sea to breed was 40%

of its earlier level (which, for most river systems, is not known!).

A 2010 DEFRA document summarises the eel plan for NW

England [1].

Somehow this document concludes that “the available

evidence ... suggests that the rivers in the North West RBD [River

Basin District] are meeting the silver eel escapement target”.

The Lune is among the most healthy of northwest rivers but even here

eel numbers have fallen significantly. The report includes the

following surveys of the Lune:

sites surveyed eel found %

1991 134 94 74%

1997 74 47 64%

2002 75 32 43%

2007 45 17 38%

So, it seems that the proportion of sites where eel were found has

halved in just 16 years. But why has the number of sites surveyed

fallen from 134 to 45? Did they give up on sites where eel were not

found before? If so, perhaps the last row should really be:

2007 134 17 13%

This would mean that the proportion of Lune sites where eel were

found fell from 74% to 13%, that is, by 82%, in 16 years. In that

case, the Lune is doing about as badly as the general figure quoted

above, 90% since 1970. Moreover, the number of sites is not that

useful a measure. We really need to know how many eels there are

at each site.

Right: A delicacy?

Right: A delicacy?

The document also includes some data on eel fishing within

the Lune region. Licences are issued for glass eel fishing and since

2005 eel fishers have to report the weight of glass eels taken. In

2007 43kg of glass eels were taken from the Lune (the report says

that this is likely to be an under-estimate). A glass eel is not very

weighty so 43kg sounds to me like a huge number of a supposedly

critically endangered species.

There is even commercial yellow and silver eel fishing on the

Lune, although the numbers taken (40kg in 2007) are, I suppose,

small. Many more eels are caught by recreational anglers but these

are supposed to be returned to the water.

The Environment Agency continues to allow eel fishing on the

Lune because “there is no evidence that the North West RBD is failing

the escapement target, and therefore no reason to restrict the eel

fisheries”. It seems to follow that there is also no reason to propose

more than modest measures within the 2010 Eel Management Plan

for the North West.

Perhaps this apparent complacency is reasonable. Maybe the

number of eels is subject to many arbitrary natural variations. In

2013 it was reported that the River Severn received ten times more

glass eels than it had in previous years; in fact, a hundred times

more than in 2009. There was no obvious explanation for this. (I’ve

heard no reports of a similar eel bonanza on the Lune.)

The most important consequence of this surprise influx was,

according to a Telegraph headline, to put “elvers back on the

menu” [2].

That’s a novel way to deal with a critically endangered

species - eat it.

[1]. DEFRA Report (March 2010), Eel Management Plans for the United

Kingdom: North West River Basin District, available on-line (or it was).

[2]. The Telegraph (May 9, 2013), Elvers back on the menu after the biggest

harvest for 30 years, European Eel Foundation.

9. Cattle on Fell End Clouds

October 2013

In August 2013 Natural England applied to the Planning

Inspectorate to erect a fence around Fell End Clouds. This was

after an earlier similar application had aroused the wrath of the

locals and had been withdrawn. Well, I like a good controversy, so

I thought I’d go to see what all the fuss is about.

Fell End Clouds lies between the slopes of Wild Boar Fell to the

east and Harter Fell to the west. The two slopes are patently very

different. Wild Boar Fell has a flat, craggy top and descends over

peat to the prominent outcrop of Fell End Clouds. Harter Fell is,

like almost all the Howgills, smooth and grassy. The slopes differ

because of the underlying geology. The top of Wild Boar Fell is

millstone grit. Harter Fell is of Silurian slate. The eastern rocks are

some 100 million years younger than those on the west, from which

they are separated by the Dent Fault.

Fell End Clouds is neither grit nor slate. It is limestone. Fell

End Clouds is a SSSI, like the more extensive limestone area of

Orton Scar, because of its geology and the flora that it gives rise to.

Looked at from afar, however, the flora seemed to consist of a lone

tree, standing prominently on the horizon.

Right: The lone tree on Fell End Clouds

Right: The lone tree on Fell End Clouds

At closer quarters, I saw short grass with few flowers other

than low-lying yellow tormentil. Apart from grass, vegetation was

largely restricted to within the grikes of the limestone pavement.

The SSSI citation says that there are seventeen species of fern

growing here. I didn’t embark on a search for them in case I found

only sixteen, thereby causing myself endless sleepless nights.

The reason for the scarcity of flora outside the grikes is said to

be the high level of sheep grazing. The solitary tree must somehow

have escaped the attentions of the sheep but otherwise all scrub and

tree species have been unable to grow.

This is where Natural England comes in, or would like to, it

seems. Natural England is, according to its website, an “Executive

Non-departmental Public Body responsible to the Secretary of

State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs”. I presume that

it is funded by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural

Affairs (DEFRA) and is therefore not independent of government.

Natural England’s purpose is “to protect and improve England’s

natural environment”.

In particular, Natural England is responsible for the welfare of

SSSIs, such as Fell End Clouds. Its proposed fence around Fell End

Clouds is intended to exclude sheep. It plans to graze a small herd

of native cattle instead. This, it contends, would enable the flora to

regenerate to a more natural state.

Left: Fell End Clouds

Left: Fell End Clouds

Fell End Clouds is isolated, with not much local community

near it - but what there is vigorously opposed the proposal, for

several reasons. First, the very idea of a fence was anathema. All

the boundaries in the region at the moment are of traditional dry

stone walls. Fell End Clouds itself has no walls to restrict the free

roaming of sheep and fell ponies.

It was feared that the proposed cattle would be hazardous to

walkers and would pollute the limited water supply that runs off

the fell. It was also argued that since the foot and mouth epidemic

of 2001 sheep grazing had already been reduced because subsidy

payments were no longer paid per head of stock. The flora was,

therefore, already regenerating (although this was not apparent to

me).

Harry Hutchinson, a local farmer, said “Natural England want

to see trees growing in the grikes between the limestone, but the

farmers think this will change the whole aspect of The Clouds,

which has been grazed for centuries” [1].

The fact that local farmers

were expected to pay (and be reimbursed later) for the fence and a

new cattle grid perhaps did not encourage a positive response.

The locals did not seem to query Natural England’s assertion

that cattle would be better for The Clouds than sheep, and perhaps

I shouldn’t either. However, I understand that the remarkable

flora of the Burren in Ireland, one of the most extensive areas

of limestone pavement in Europe, depends upon a distinctive

‘winterage’ cattle-grazing system that has evolved. Cattle graze the

lowlands in summer and are transferred to the limestone uplands

in winter. This is partly because of the lack of water on the uplands

in summer. The result, of course, is that the cattle are not grazing

when the limestone flowers and shrubs grow. I don’t know if a

similar regime is proposed for The Clouds.

Right: Limekiln on Fell End Clouds

Right: Limekiln on Fell End Clouds

The crux of the matter is a basic question that we will no doubt

meet again: What is natural? Or, perhaps better, which form of

nature is to be preferred? And why? And by whom?

Is the lone tree on Fell End Clouds an aberration, an anomaly, an

accident? Is it unnatural for it to be there? Or is the rest of Fell End

Clouds unnatural? Should the tree really be part of a woodland of

similar trees growing unhindered from the grikes? (This particular

tree, a sycamore, should not be there but that’s another story: let’s

pretend it’s an oak.)

The appeal to ‘tradition’ is unconvincing. Dry stone walls are

not that old and are certainly not natural. Sheep may have grazed

here for centuries but that doesn’t mean that they will or should be

here indefinitely. A few centuries ago we had wild boar on Wild

Boar Fell.

Legally, it is, I suppose, up to Natural England to decide what is

natural. However, whatever criteria they use will be tempered by

the local reaction and that reaction will, in general, be influenced by

factors other than what is best for nature.

Personally, I doubt that Fell End Clouds is worth Natural

England engaging in a protracted dispute over. The locals will no

doubt disagree with that opinion but welcome the conclusion. In

my opinion, Fell End Clouds is an intriguing and attractive area,

enlivening this particular environment, but it is not a patch on the

limestone pavements of Orton Scars and the Yorkshire Dales.

Some people will find Fell End Clouds more interesting as a rural

industry wasteland than for its ‘naturalness’. There are the remains

of a quarry and some fine lime-kilns. The pavements themselves are

disfigured by several excavated trenches where various minerals,

such as galena for lead, were extracted. But industrial wastelands

are outside my scope, so I will leave it at that.

[1]. Cumberland & Westmorland Herald (December 19, 2012), Storm over

fencing plan for The Clouds.

10. Pink-Footed Geese in the Wyre-Lune Sanctuary

February 2014

What is the difference between a goose and a duck? I am

increasingly plagued by such naive questions - questions

that hadn’t bothered me much before, and questions that I

am embarrassed to realise that I cannot answer with any precision.

Perhaps it is unreasonable to seek precision. The meanings of

words such as ‘goose’ and ‘duck’ have evolved informally over

the centuries. They may not be the same for different people, at

different times, or in different places. Many birds called ‘goose’ in

the southern hemisphere are really shelducks. ‘Goose’ and ‘duck’

are not terms invented by us to have defined meanings, such as, say,

‘proton’ and ‘neutron’, where we may demand a precise distinction.

They are more like, say, ‘energy’ and ‘impulse’, everyday words

that scientists have co-opted and assigned precise definitions that

do not entirely accord with their everyday senses.

Perhaps I cannot do better than “geese are bigger than ducks;

geese honk, ducks quack; geese fly in formation, ducks don’t; male

and female geese look similar, male and female ducks don’t”. These

generalisations are only more or less true. I am coming to terms with

this unavoidable imprecision but I am flummoxed to discover that

the hallowed scientific classification scheme (kingdom, phylum,

class, superorder, order, family, subfamily, tribe, genus, species) is

not completely precise either.

When a species is defined scientists determine the salient

features that define it. Some other scientists, however, may consider

different features to be more salient for defining those species.

New data may become available, for example, from the study of

fossils. New features may be discovered, for example, from gene

analysis. After discussion and dispute, a new classification may be

agreed. So, the much-vaunted ‘tree of life’ has the odd property

that branches may be chopped off and grafted on elsewhere.

It seems that the classification scheme for waterbirds is in a state

of flux at the moment. The Anatidae family includes ducks, geese

and swans but not some waterbirds that look duck-like to me, such

as grebes and coots. This illustrates the well-known saying “if it

looks like a duck, it may not be a duck” (or something like that).

However, the definition of the Anatidae subfamilies, and

the species within them, is not agreed upon. Anatidae has been

suggested to have three or six or nine subfamilies. At the moment,

Wikipedia lists ten subfamilies.

One subfamily, Anserinae, contains

what I would think of as swans and geese. The others are various

forms of duck. Even now, several waterbirds, such as the mandarin

duck, are still swimming in the ‘unresolved’ pool.

Right: The Wyre-Lune Sanctuary from Lane Ends

Right: The Wyre-Lune Sanctuary from Lane Ends