Four Men in Their Boots, Day 7

... Keswick ...

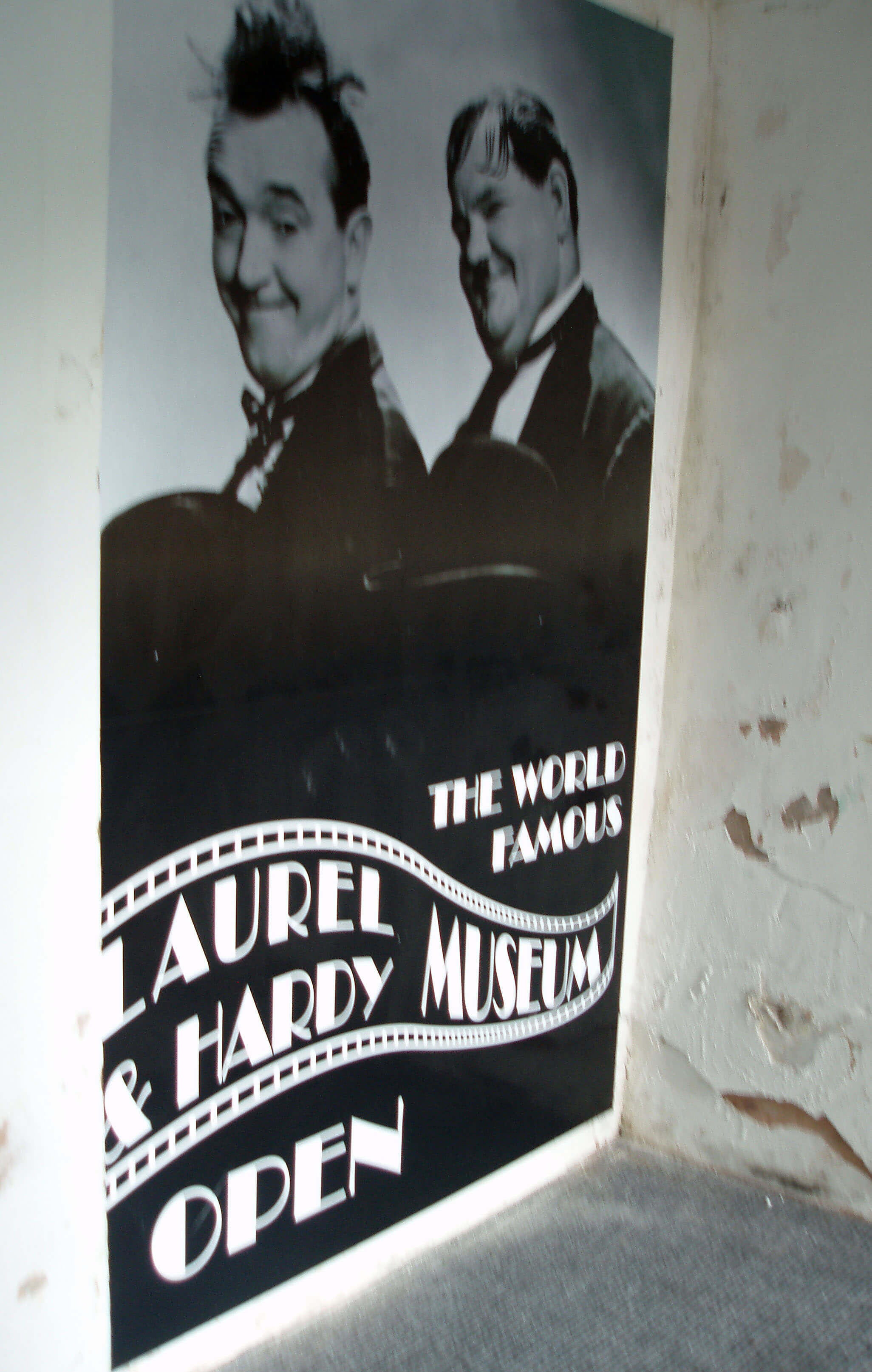

By the morning a gale had blown the rain away. But we were left with the wind ... and what a wind it was! We were buffeted about as we walked through the streets of Keswick and could hardly imagine what it would be like on the fell tops. We passed the world famous Cumberland Pencil Museum, struggling hard to resist the attractions of the World’s Longest Pencil, 7.91 metres, to be exact. After the difficulties on Skiddaw, the maps had been left

in my hands, without comment. Across the bridge we took a

footpath through Portinscale and Ullock and on to Braithwaite,

where we found the rather fine looking Coledale Inn. Harry

had done well arranging our accommodation for the nights

and here we seemed to have something a bit special, perhaps

to mark our halfway point.

I looked forward to returning for a good night’s rest,

after our walk around the Coledale horseshoe. We jettisoned

everything we didn’t need, which did not include our wind-proof walking gear, and set off brightly.

After the difficulties on Skiddaw, the maps had been left

in my hands, without comment. Across the bridge we took a

footpath through Portinscale and Ullock and on to Braithwaite,

where we found the rather fine looking Coledale Inn. Harry

had done well arranging our accommodation for the nights

and here we seemed to have something a bit special, perhaps

to mark our halfway point.

I looked forward to returning for a good night’s rest,

after our walk around the Coledale horseshoe. We jettisoned

everything we didn’t need, which did not include our wind-proof walking gear, and set off brightly.

The storm and gale had brought a crystal clarity to the air. Looking back, we could see every detail of Skiddaw, none of which we had seen the day before. However, we didn’t look back much because we were inspired by the view ahead. Our route seemed laid out before us, no distance at all.

... Grisedale Pike ...

As we battled our way up to Grisedale Pike, Harry began waxing lyrical, as all waxing is, about the wonders of the natural world. He seemed on the verge of becoming overcome with emotion. Now I have as much appreciation of the natural world as the next person but it seems unmanly to me to get over-emotional about it. I blame those poets, again. So, in order to restore a proper perspective, I began to focus on the unnatural elements of the scene.I pointed out the miles and miles of the Whinlatter Forest conifer plantations visible off to the right and also the ruins of Force Crag Mine, far below us to the left. This led to a protracted discussion about the origins and purpose of the forest and mine, the conclusion of which was that they must have been involved in the manufacture of the esteemed Cumberland Pencils, the lead or graphite from the mine being enclosed in wood from the forest.

This isn’t true but the others were so satisfied with their explanation that I was content to leave them with it. In fact, although lead was mined from Force Crag Mine in the 1800s the pencil-makers used graphite from Borrowdale. The mine functioned, on and off, until the 1990s. Today, the mine is owned by the National Trust, who are not enamoured of mines in the Lake District and will no doubt ensure that the mine stays off.

... Hopegill Head ...

We walked on past Grisedale Pike to Hopegill Head, keeping well clear of the edge to avoid being blown over Hobcarton Crags. I began to notice the number of people who shouted a “Hi Harry” to Harry. His purple-pink outfit made him easily recognisable but I was surprised that, even with his exceptional affability, he had managed to get on first-name terms with quite so many people during our walk. Some even added “Keep going, Harry, you’ll make it” or “Hope the blisters aren’t too bad, Harry” as though they were fully familiar with the nature of his expedition.Most of what was said was lost in the wind, which whipped the words and much else besides over the mountain edge. “How the wind doth ramm!” floated into my mind, which, I remembered, is part of ‘Winter is Icumen In’:

Winter is icumen in,

Lhude sing Goddamm,

Raineth drop and staineth slop,

And how the wind doth ramm!

Sing: Goddamm.

This is a parody of the 13th century English round ‘Sumer is Icumen In’ by the American poet Ezra Pound. Americans are proud of their liberty, and it is a liberty to mock our ancient songs just because they don’t have any, and to adopt our currency as a surname, too.

I began to sing the song, to the tune of the mice in Bagpuss, confident that nobody would hear me in the gale. Richard, however, noticed my lips moving and thought that I was speaking to him. I explained that I was singing a song appropriate to the conditions and, after persuasion, I sang it aloud to them all.

Given their interest, I tried to get them to join in the round, but they couldn’t get the hang of it at all. They seemed incapable of entering at the correct point, on the “Lhude”, and if I ever did get them all going together they tended to treat it as a race to the “Sing: Goddamm”.

After a while, I suspected that they were failing on purpose but, as they seemed to enjoy the ending so much, we settled on me singing the song and them all joining in loudly on the “Sing: Goddamm”. It was almost as if the Goddamm were directed at me. And so singing, we strode from Hopegill Head down past Eel Crag, the “Goddamm”s alarming a few nervous walkers.

... Grasmoor ...

With the team in good spirits, I mentioned the detour that I

had planned to Grasmoor and, with no-one daring to decline,

we struggled up the long grassy slopes against the ferocious

gale. At the top, we stood, braced against the wind, to survey

the scene, with our imminent challenges of Pillar, Scafell and

Bowfell arrayed to the south.

We turned, prepared to be blown back down Grasmoor,

only to find that the backpacks of Tom and Richard were no

longer with us. They had put them down at the summit cairn

and, being much lighter than on previous days, they had been

whisked by the wind over Dove Crags.

With the team in good spirits, I mentioned the detour that I

had planned to Grasmoor and, with no-one daring to decline,

we struggled up the long grassy slopes against the ferocious

gale. At the top, we stood, braced against the wind, to survey

the scene, with our imminent challenges of Pillar, Scafell and

Bowfell arrayed to the south.

We turned, prepared to be blown back down Grasmoor,

only to find that the backpacks of Tom and Richard were no

longer with us. They had put them down at the summit cairn

and, being much lighter than on previous days, they had been

whisked by the wind over Dove Crags.

I condescended to wait while they scrambled down the precipitous cliffs to retrieve them. After all, it was not my fault that they were foolish enough to lose them. Harry, ever the helpful colleague, opted to scramble down with them. I sat day-dreaming at the panorama for quite a while. I forgot all about them but after about forty-five minutes I began to be a little concerned that they hadn’t re-appeared. I tentatively peered over the edge of the crags, fearing being blown over myself, but they were nowhere to be seen.

I became quite worried and began to think about calling out the Mountain Rescue Service, for the three of them were not really equipped for rock-climbing. And then I saw them, far off to the right, on the slopes of Grasmoor, having emerged from the crags much further east than where they went down. I walked fast to catch them up. They blithely explained that they had taken a short-cut on the crags in order to catch me up on Crag Hill. I had distinctly said that I would wait for them at the Grasmoor cairn and I am not used to my instructions being misunderstood. I was quite miffed but the other three seemed in even better spirits than they were as we strolled along the long ridge to and over Causey Pike.

... Braithwaite ...

On our return to the inn, there was an embarrassing incident with the receptionist. There had, it appears, been some misunderstanding as a result of Harry having asked for two doubles. She had thought he was referring to beds rather than rooms, a perhaps reasonable inference in this day and age. I, however, would not countenance the former.After a long wrangle with the manager, it was eventually agreed that I would have a room with a double bed and the other three would share the other room, into which an extra bed would be moved. So that was satisfactorily resolved and, after a fulsome meal, I departed from the others to enjoy the restful night that I had looked forward to all day.

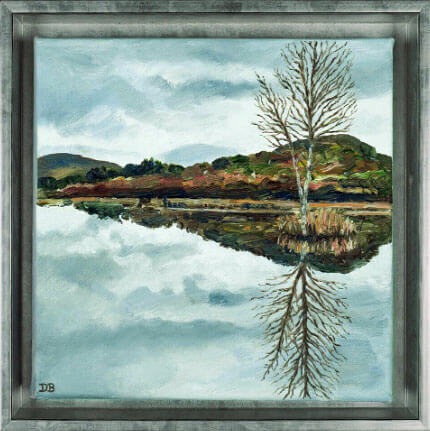

Photos: The Cumberland Pencil Museum; The view as I waited on Grasmoor.

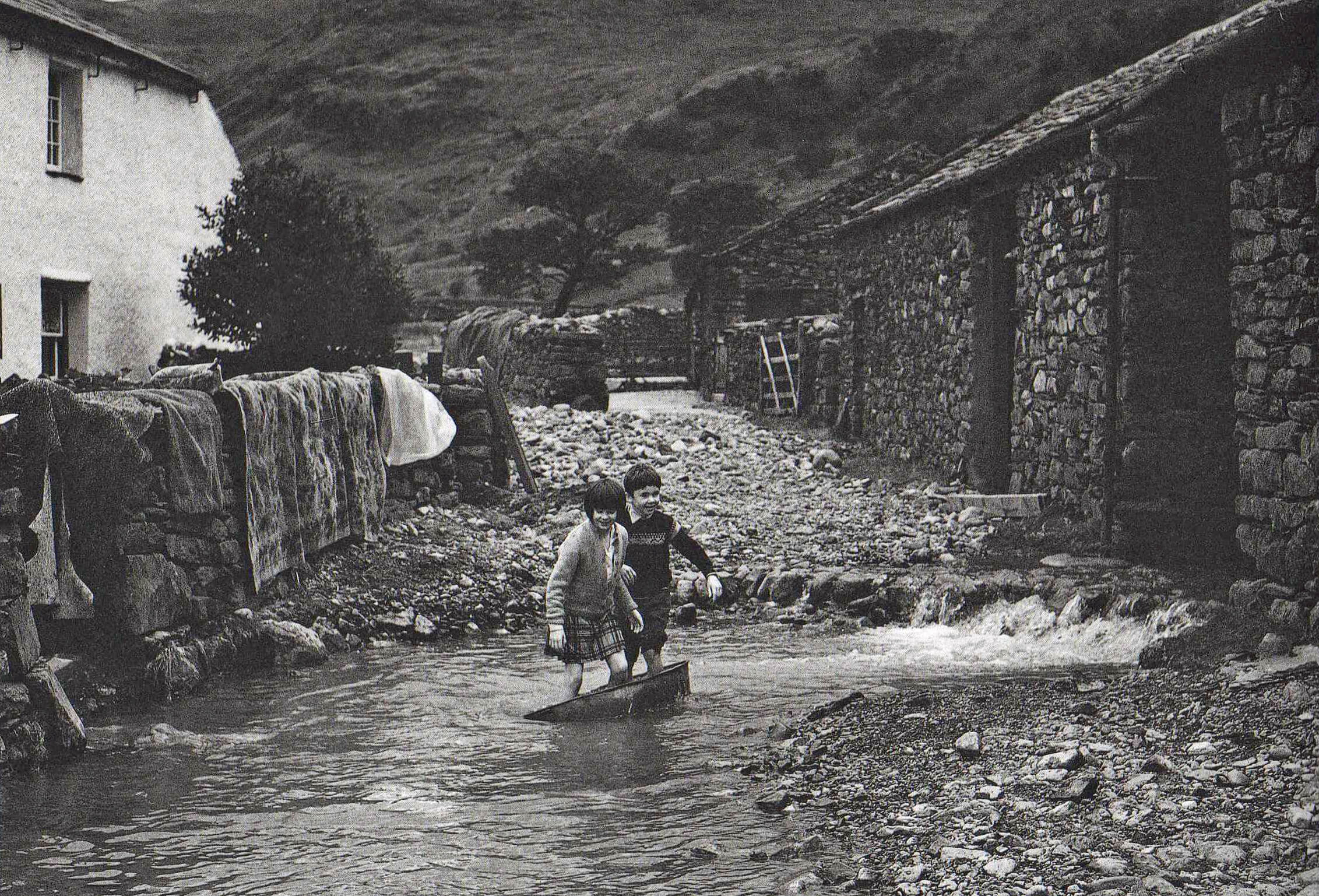

The Tale of Squire Ruskin

Little Johnnie Ruskin was always little when he was little. But he had big ideas. When his parents brought him to the Lakes for a holiday at the age of eleven he didn’t just say thank you: he wrote a poem of over two thousand lines to do so.His father had big ideas for little Johnnie too. More importantly, he also had a lot of money, which he had earned by selling alcohol. He sent little Johnnie to the best universities, although Johnnie didn’t feel the need to do much studying there.

As he grew bigger, little Johnnie didn’t know what to do, he was so good at everything. But his father was rich enough that he didn’t really need to do anything anyway. So he went on a few tours. He met lots of famous people, who all said “Who are you?”. When he got back he resolved to become famous too.

He liked to paint, but his paintings weren’t particularly good. He liked to write, but to begin with he was too shy to put his own name on what he had written. He liked little girls, but they didn’t like him. But most of all he liked to tell other people what to like.

He began by telling people what buildings they should like. And then what paintings they should like. He said that the old masters such as Michelangelo were too old: youngsters like Joe Turner were much better. Joe’s paintings were so vague that ordinary people couldn’t see that they were good.

As he became famous, he married Miss Effie. But they were never close, and they became even less close when she ran off with one of his friends.

This upset him. He began to tell people what paintings they should not like. But some painters didn’t like it when he told people not to like their paintings. Jimmy Whistler, a butterfly artist from over the pond, even took him to court. So he gave up art. Instead, he began to tell people how to live.

This was much more difficult. After all, he hardly knew how to live himself. He liked to spend all day looking at lichens. So he said that they shouldn’t make poor people work in dirty factories: they should be able to look at lichens all day too. Unfortunately, poor people didn’t really want to look at lichens much: they preferred to drink alcohol, like his father sold.

He wrote lots of letters, which he called Fors Clavigera, to the poor people. We, who have studied Greek, know exactly what he meant. But the poor people threw the letters in the bin.

Johnnie became even more fed up. So, to cheer himself up, he bought a nice, big house overlooking a lake. He was a bit lonely but he liked to look out of his windows at a beautiful scene not spoiled by any of those poor people that he tried to help.

People asked who lived in the big house on the hill. They were told “The squire, Ruskin”. Some people wondered what rusking involved.

He made up a word ‘illth’ to mean ill-being, the opposite of well-being, and he began to suffer more and more from it. Eventually he died, as even good people like Squire Ruskin must do. But his ideas, whatever they were, live on. They have influenced many important people, including Leo Tolstoy, Marcel Proust, Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and John Prescott.

Photos: The view from Squire Ruskin's house; Squire Ruskin, his valet and his dog.

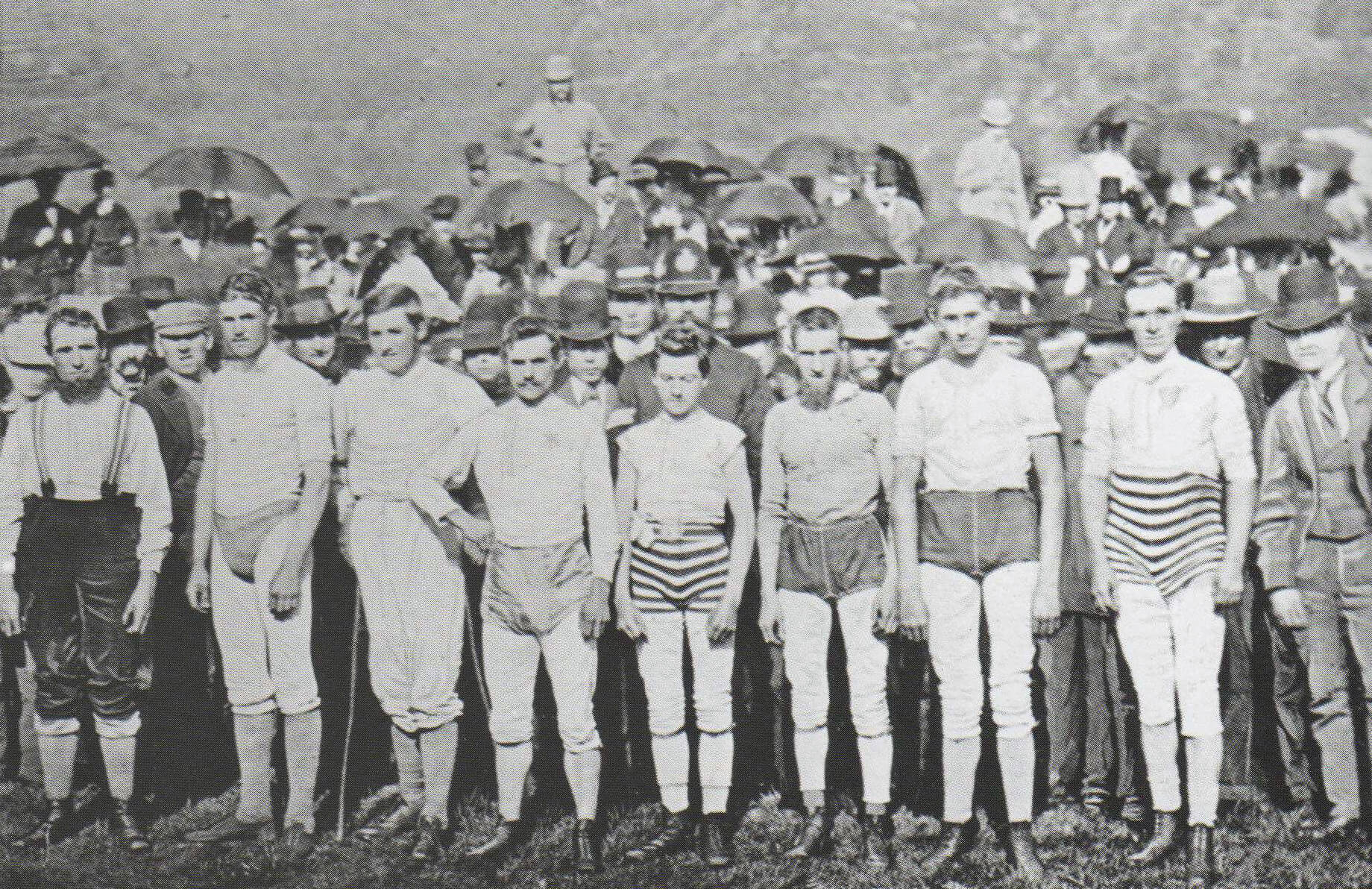

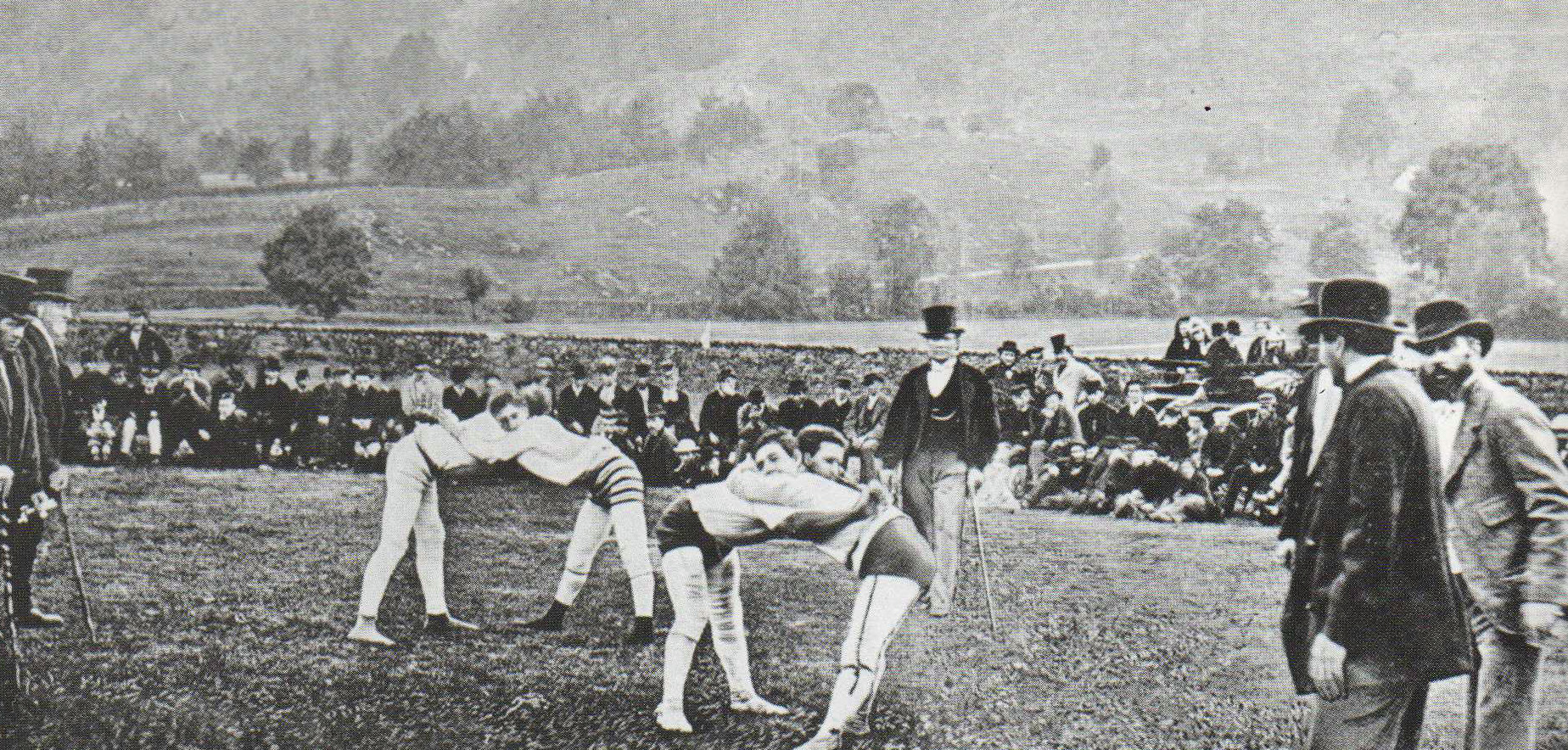

Hawkshead 3 Windermere 4

The Hawks were desperately unlucky to lose an action-packed

seven-goal thriller at the rain-soaked Gillie Ground, after the

man in black failed to spot a blatant infringement in the dying

seconds by the Wanderers’ custodian. Three times the brave Hawks

had fought back to parity with the table-toppers, only to succumb

to a late own goal.

The Hawks were desperately unlucky to lose an action-packed

seven-goal thriller at the rain-soaked Gillie Ground, after the

man in black failed to spot a blatant infringement in the dying

seconds by the Wanderers’ custodian. Three times the brave Hawks

had fought back to parity with the table-toppers, only to succumb

to a late own goal.

Manager Harry Hopkins said “I’m proud of all the lads. I couldn’t ask for any more. They worked their socks off. We’ll take the positives and move on to the next match”.

The game kicked off with the rain and wind blasting down Langdale ...

Sorry to interrupt your flow, but doesn’t this belong on the sports pages?

What of it? I’ve infiltrated all the other sections of this paper before. I’ve written reports on weddings, funerals, concerts and fights outside the Harassed Herdwick; I’ve contributed recipes, horoscopes, letters to the editor, advertisements and weather reports. Our readers, deficient in gorm, cannot tell the difference. Or perhaps they find that my efforts provide more entertainment for their fifty pence than the real thing.

Yes, but we don’t want to waste your unique talents on football reports. Anybody can write that stuff.

This is not a football report. I am making an attempt on the world record for clichés, currently held by Barry Bollinger of the Daily Mirror, who recorded 27.3 clichés per 100 words on the Germany 1 England 5 game. I have a theory that clichés are better for more mundane games, and you can’t get more mundane than Hawkshead versus Windermere.

I see. Let us pray proceed.

A bright opening from the Hawks forced the promotion favourites onto the back foot, before a breakaway goal on the half-hour silenced the Hawks’ faithful supporters. The Hawks responded immediately when Nobby Drummond nodded home unmarked, with the Wanderers defence appealing vainly for off-side ...

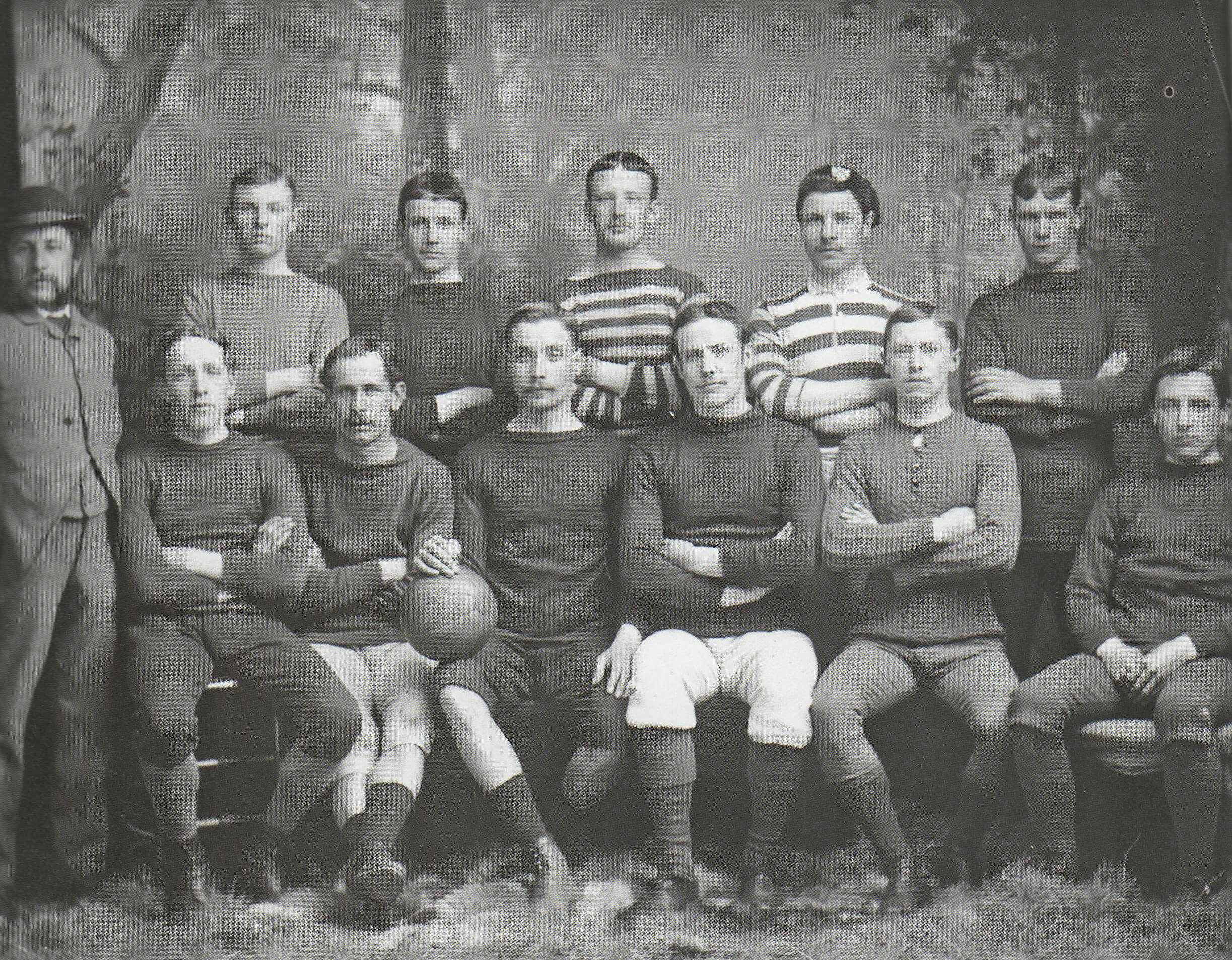

Photo: Hawkshead Athletic football team.

Pen Your Pimp: Another Book for Offcomers

Pen Your Pimp, by Tom Bumfit (Strudelgate Press, £14.99), 235 pages

with 15 intricate pen-and-ink drawings. There is also a Pen Your

Pimp DVD (£14.99), showing all the manoeuvres in detail, with

commentary by Tom Bumfit.

Pen Your Pimp, by Tom Bumfit (Strudelgate Press, £14.99), 235 pages

with 15 intricate pen-and-ink drawings. There is also a Pen Your

Pimp DVD (£14.99), showing all the manoeuvres in detail, with

commentary by Tom Bumfit.

Offcomers may be excessively excited by this title. In the Cumbrian dialect, pimp is five (in the Keswick version: yan, tyan, tethera, methera, pimp, ... ) when shepherds count their sheep. And five sheep is the usual number penned in Cumbrian sheep-dog trials. So, Pen Your Pimp is a description of the traditional Cumbrian sport of sheep-dog trialling. This book presents all the rules and techniques of trialling but the majority of readers will enjoy most the anecdotes through which Tom Bumfit enlivens the text.

There was, for example, the controversial occasion when several sheep-dogs were disqualified from the National Championships for being colour-prejudiced. They had been trained only with white sheep. If, in the competition, the dogs were presented with five sheep one of whom happened to be black then they were flummoxed. They sometimes penned only the four white sheep and left the black sheep out. The judges realised that this would not look good on One Man and His Dog and promptly banned the dogs. The dog owners duly objected, arguing that there was nothing in the rules to stop them insisting on only white sheep. The judges banned them too for being colour-prejudiced.

In another chapter, Bumfit explains whistling techniques via the story of the ventriloquial whistler who disrupted many trials in the 1970s. Several sheep-dogs, not to mention their handlers, became permanently depressed as a result of the antics of the ventriloquial whistler. He was only identified in 1978 after a detailed statistical analysis of the results of the previous decade. It was realised that the culprit could not ventriloquially whistle his own dog and that he would probably resort to this practice only after an unsuccessful run of his own. He was hounded out of Cumbria.

The Duke of Westminster’s A to Z

When the dear 6th Duke of Westminster sadly departed from us he left his estate

and title to Hugh, the 7th Duke of Westminster. As the latter was a mere stripling of 25 the 6th Duke also left

an A to Z of advice on how to cope with unwanted and unwarranted celebrity and wealth. Here it is:

When the dear 6th Duke of Westminster sadly departed from us he left his estate

and title to Hugh, the 7th Duke of Westminster. As the latter was a mere stripling of 25 the 6th Duke also left

an A to Z of advice on how to cope with unwanted and unwarranted celebrity and wealth. Here it is:

A is for Aunt Miriam, whom you have never met because she has been incarcerated in the east wing since she set fire to Harold Macmillan’s trousers after he rejected her advances in the summer of 1962. Poor Harold never recovered from this incident. He was still rather off-kilter when in the notorious ‘Night of the Long Knives’ he decapitated seven members of Cabinet.

B is for boots. It is jolly muddy around our little country house at Abbeystead. Since you have infinite wealth buy the best boots there are. I recommend Le Chameau’s Jameson Unisex Standard at £385. You buy one and get one free. Jolly generous. I’ve said ‘unisex’ because I’m not sure of your inclinations in that direction. We never did have that chat. Sorry.

C is for charities. You will need to be patron of a few hundred of them, to show your commitment to society, whatever that is. I used to enjoy the board meetings of the Society for the Preservation of English Real Men, which aims to stick up for men in our increasingly female-dominated world. The japes we got up to! But it may not be your kind of thing?

D is for Daniel Snow, who is one of your brothers-in-law. He’s in television, which is something ordinary people look at. If he turns up with cameras and what-not turf him out. People have no business looking at what we do here.

E is for Eaton Hall, our home in Cheshire.

It is jolly big. You'll need to get more familiar with it than I managed.

Staff hide away. One girl had a five months holiday there. I

eventually found her wandering in the old stables, where she said that she had become lost and was

living on a diet of mice and hay.

Unfortunately, the wretch was unable to resume her duties, which involved the daily combing of the Duchess’s wigs.

E is for Eaton Hall, our home in Cheshire.

It is jolly big. You'll need to get more familiar with it than I managed.

Staff hide away. One girl had a five months holiday there. I

eventually found her wandering in the old stables, where she said that she had become lost and was

living on a diet of mice and hay.

Unfortunately, the wretch was unable to resume her duties, which involved the daily combing of the Duchess’s wigs.

F is for fishing, an activity for the real English gentlemen. Your great-great-grandfather Arthur – known to all as Bendor or ‘bend or’ or azure, a reference to the family armorials lost in the famous case of Scrope v Grosvenor heard before the Court of Chivalry in 1389 – was a jolly good fisherman. They say that in his old age, as he spent more and more time standing in the river, he took on the characteristics of his beloved fish. But not sufficiently so, for he drowned whilst grappling with a large trout. Even so, after his partial cremation he was considered to be delicious.

G is for George, of whom you are the godfather. I need hardly say that it is your duty to inculcate in him the habits of the English gentleman (his parents will be much too busy explaining the complexities of royal life). In particular, the sooner he is given a gun to shoot grouse the better. If he should inadvertently dispose of some of the lesser members of the royal family then I am sure that his parents wouldn’t mind.

H is for Horse and Hound, my complimentary subscription to which should pass on to you. It has been in the family since the magazine began in 1884. It is nearly all about horses nowadays, with little about hounds – although there are jolly interesting pieces about fox-hunting from time to time. Essential reading. My dear wife is a close friend of the editor, Lady Levershoome. They were at Eton together. The teachers never noticed them but the boys did.

I is for inheritance, which is all yours. If your elder sisters should come knocking asking for fair shares then tell them that fairness has nothing to do with it. That equality nonsense does not apply to dukedoms, and it never will as long as esteemed eminences such as our dear friends Jacob Rees-Mogg and Lord Dallyrymple have a say in the matter.

J is for je ne sais quoi. We superior men have that indefinable quality that raises us above lesser men. As with a balloon, it is better not to try to pin it down.

K is for knickerbockers. I leave you four wardrobes full of knickerbockers. They were my favourite garments for the lower limbs until they unaccountably fell out of fashion, the garments, that is, not my limbs. I tried to make knickerbocker glories with them but with only modest success. If you cannot find a use for them take them along to the next golf club jumble sale.

L is for Loelia Ponsonby, the most exotic leaf on the family tree. She was the

third wife of the second Duke, but the marriage, despite getting off to a flying start with Winston Churchill

as best man, was described as “a definition of unadulterated hell” by James Lees-Milne (whoever he was). After

her divorce, Loelia became a needlewoman and magazine editor. She sewed every copy herself.

She is known for saying “Anybody seen in a bus over the age of 30

has been a failure in life” – but what the age of the bus has to do with it, I don’t know.

L is for Loelia Ponsonby, the most exotic leaf on the family tree. She was the

third wife of the second Duke, but the marriage, despite getting off to a flying start with Winston Churchill

as best man, was described as “a definition of unadulterated hell” by James Lees-Milne (whoever he was). After

her divorce, Loelia became a needlewoman and magazine editor. She sewed every copy herself.

She is known for saying “Anybody seen in a bus over the age of 30

has been a failure in life” – but what the age of the bus has to do with it, I don’t know.

M is for marriage, which I am sorry to say you must contemplate if only to perpetuate the dukedom in the traditional manner. The only advice I can give is to avoid anyone called Loelia, if such a person exists.

N is for nodding acquaintance, on which you must be with all you see about the estate. A nod is enough. It shows that you have acknowledged their existence, which is all they need to lighten their dreary lives. On no account address anyone by name. It is impossible to remember them all and mistakes can cause untold misery. I was once mangling with a young maid in the laundry and at a sensitive moment moaned “Oh, Joan”, causing Jean to storm off leaving my underwear unmangled.

O is for Ouija board. You will find mine in the twelfth bedroom. It has been a great comfort to me, to be able in times of stress to seek advice from my forebears. If you ever think I can help please get in touch.

P is for parsimony. Look after the pennies and the billions will look after themselves, my granny used to say. Ordinary people know that we are jolly rich but they don’t like us to flaunt it. It is better not to offer to pay for anything if you are ever in the unlikely situation that a payment is required. Ordinary people are, I find, extraordinarily grateful for the opportunity to show that they are momentarily on a par with us.

Q is for queue. This is probably something that you will never encounter yourself but you may be puzzled by the behaviour of ordinary people. It seems that when they want something that is not immediately available they stand behind someone who has already wanted it. Very strange! Once, when I lost my valet at Covent Garden, I had to stand in a queue for the lavatory. The unaccustomed delay led to an unfortunate accident. On balance, though, sitting in the foyer in wet knickerbockers was preferable to sitting through the third act of Gotterdammerung.

R is for rattlesnake. I trust that you will look after my pet rattlesnake. I found it great company on those dreadful occasions when we were visited by people from something called Natural England. They go on and on about things we’re not supposed to kill on the estate. What do they think an estate is for? However, they were always charmed by the rattlesnake. Once it escaped during luncheon and the Minister for the Environment nearly stuck her fork in it, which would have been the end of her, and no bad thing too.

S is for shooting stick. I have been given many of these but I haven’t managed to shoot anything with any of them.

T is for tweed, essential wear for all occasions, even, or especially, in bed.

My father, who was one of identical twins, was known as Tweedledee because he was not dum, unlike his twin sister.

T is for tweed, essential wear for all occasions, even, or especially, in bed.

My father, who was one of identical twins, was known as Tweedledee because he was not dum, unlike his twin sister.

U is for upper crust. Someone who was ushered off the moor at gun-point shouted at me that I was a member of the ‘upper crust’. I asked our chief cook what on earth that meant. He said that it’s better than being a member of the lower crust or even the side crust. Since then I have never dared to eat the crust of any loaf.

V is for virtus non stemma, the family motto. As you know, it means ‘virtue not pedigree’. Whichever of our ancestors devised this motto may have had a great sense of irony but it is best to assume that he just got his Latin back to front.

W is for Westminster, where we have a palace and 650 specially appointed people to work on our behalf. However, some of these are distressingly independent-minded. The like-minded ones, however, are always jolly good company for a chin-wag and a touch of venison.

X is for xenodochium. This is the room in the servants’ quarters at Abbeystead where we quarantine any strangers found wandering on the estate. They keep saying they have a right to roam, whatever that is. The ones with binoculars are particularly shifty. Our head groundsman returns them to Preston Lost Property Office on the first Monday of the month.

Y is for yesterday, my favourite day.

Z is for sleep, of which we deserve plenty. The third Duke was a great sleeper. He usually needed eight hours sleep a day, and nine hours a night. He fell asleep on the eve of the war in 1914. He awoke eight days later, a couple of hours before his funeral. The Duchess thought of the many great and good people who had travelled far for the occasion despite the sombre national mood and decided not to disappoint them because of a technicality.

Four Men in Their Boots, Day 8

... Braithwaite ...

I came down to breakfast in my normal timely fashion

and waited for the others. They arrived half an hour late,

dishevelled and argumentative. I dared not ask if they’d had a

good night.

Tom glared at the breakfast menu and immediately

confronted the waiter.

I came down to breakfast in my normal timely fashion

and waited for the others. They arrived half an hour late,

dishevelled and argumentative. I dared not ask if they’d had a

good night.

Tom glared at the breakfast menu and immediately

confronted the waiter.

“Is the potted char available today?”

“Yes, indeed, and delicious it is.”

“Is it local char?”

“Oh, yes, everything on the menu is local if it is possible to be so.”

“How local?”

“How do you mean, sir?”

“Well, I assume the char comes from some lake. Do you know which one?”

“Er, no. I don’t think so. Does it matter?”

“It matters to me.”

“Well, in that case I think I’d better get the manager. Please excuse me.”

I interrupted before he dashed off. “Before you go, could I say what I would like. We’re a little behind schedule. I’d like the potted char, followed by the full English, with black pudding and mushrooms, with coffee, black.”

“And the same for me” said Richard. “And me” added Harry.

After five minutes, the manager came to our table. “How may I help you?” he beamed.

“Well, I’m interested in your potted char” said Tom. “I’d like to know where it comes from.”

“It comes from Jim Sproke’s Furness Fish Supplies. And Jim supplies only the best fish. You may rest assured of that.”

“No, no. Which lake does the char come from?”

“Oh, I see. I’m afraid I don’t know. Does it matter?”

“It matters to me.”

“Well, in that case I’d better ring Jim Sproke. Please excuse me.”

The three of us polished off our potted char. “Delicious” we agreed.

After ten minutes, the manager returned. “Jim says that the char comes from Windermere. I trust that is satisfactory, sir.”

“It may be satisfactory for Jim, and for you, and for these three. But what about the char?”

“What about them?”

“Aren’t you aware that the char were trapped in Windermere at the end of the last Ice Age and it is one of England’s rarest fish? And it is becoming rarer still through being caught and fed to ignorant buffoons like these three.” We tucked into our black pudding.

“No, I wasn’t aware of that” said the manager.

“Well, you should be. It should be an offence to serve endangered species as food. I suggest that you return the char to Windermere, where they belong.”

“But they’re dead, sir. In pots.”

“Well, return them to Jim and tell him where to stick them. It’s a disgrace.” And he stormed off without having any breakfast, especially not the potted char.

I think the strenuous exercise was beginning to affect the emotions. Tantrums from Richard on Blencathra, sentimentality from Harry on Grisedale Pike, and now this. At least I remained in full command.

Half-an-hour later we gathered on the steps of the inn, with fully-loaded rucksacks. I thought it best to try to clear the air. “What was that all about, Tom” I said.

“Thomas to you” he said.

“OK. Thomas. What’s the problem?”

“Well, I’m as fond of good food as anyone, but we should all be aware of what we are eating. Char should not be eaten. And if you knew what was in that black pudding you wouldn’t eat that either.”

I preferred not to know, so we set off, at last, from Braithwaite.

... High Spy ...

We made our way across Newlands Beck and soon reached

the slopes of Catbells. We paused briefly at the top so that

we could admire the view over Derwent Water whilst Harry

chatted to all the grandmothers and infants that Wainwright

promised.

We hadn’t time to dally so I hurried the team on down

to Hause Gate and up to Maiden Moor, the top of which we

passed over without being quite sure where it was. It didn’t

matter, as we pressed on to High Spy, where I permitted a

refreshment break.

I sat there admiring the view of peaks we’d already

conquered such as Helvellyn, Skiddaw and Grasmoor, and,

ahead, the dome of Great Gable, with Scafell and Scafell Pike

to its left. The highest peaks of our expedition were well and

truly in my sights now.

We made our way across Newlands Beck and soon reached

the slopes of Catbells. We paused briefly at the top so that

we could admire the view over Derwent Water whilst Harry

chatted to all the grandmothers and infants that Wainwright

promised.

We hadn’t time to dally so I hurried the team on down

to Hause Gate and up to Maiden Moor, the top of which we

passed over without being quite sure where it was. It didn’t

matter, as we pressed on to High Spy, where I permitted a

refreshment break.

I sat there admiring the view of peaks we’d already

conquered such as Helvellyn, Skiddaw and Grasmoor, and,

ahead, the dome of Great Gable, with Scafell and Scafell Pike

to its left. The highest peaks of our expedition were well and

truly in my sights now.

My companions, inspired by the name of High Spy, began - would you believe it? - a game of I Spy. The childishness of grown men never ceases to amaze me. Here we were, perched on one of the finest viewpoints of the central fells, and all they were interested in was I Spy. I ignored them. But after Harry had stumped them for 10 minutes with ‘L’ I thought it was time to move on. L, it transpired, was for Helvellyn. I suspect Harry really thought it was.

As we set off, I said “I’ve got one for you .. I spy with my little eye something beginning with A”. I knew that would distract them while we dropped down to the tarn and then clambered up the steep slopes to the top of Dale Head. As we strode along Hindscarth Edge, I thought I’d put them out of their misery. “Give up?” I said. “OK, A is for Aystacks”.

They groaned, in not too friendly a fashion, I felt. Then after a few minutes deep thought Richard said “I don’t believe you could spy Haystacks back there on High Spy”.

“Would you like us to go back and check?” I said.

Of course, he didn’t. You can’t, in fact, see Haystacks from High Spy but I knew that they wouldn’t think of Haystacks anyway. They reacted as though I had violated the spirit of the game. How childish can you get?

... Buttermere ...

Despite an air of mutiny, we detoured slightly to the peaks of

Hindscarth and Robinson. One has a duty, I feel, to visit all the

tops that one passes near by, although my companions didn’t

seem to agree.

They said that they preferred to walk in a direct line. So

I marched them all straight through the bog of Buttermere

Moss, on the slope from Robinson to our hotel in Buttermere.

They complained bitterly as our boots filled with mud but it

didn’t concern me in the slightest.

Because I anticipated that a large parcel awaited me at

the Fish Hotel.

Despite an air of mutiny, we detoured slightly to the peaks of

Hindscarth and Robinson. One has a duty, I feel, to visit all the

tops that one passes near by, although my companions didn’t

seem to agree.

They said that they preferred to walk in a direct line. So

I marched them all straight through the bog of Buttermere

Moss, on the slope from Robinson to our hotel in Buttermere.

They complained bitterly as our boots filled with mud but it

didn’t concern me in the slightest.

Because I anticipated that a large parcel awaited me at

the Fish Hotel.

If, like me, you avidly study the descriptions of great expeditions to, say, the North Pole or into the jungles of Africa, you will know that there is one thing that is left undiscussed. That is clothing. It goes without saying that the great explorers travelled for months on end without a change of clothes.

Harry, as was becoming increasingly clear, was following the same policy. Richard, on the other hand, thoroughly washed his one set of clothes every night. Some mornings they were still wet as we set off, which may explain his grumpiness. Thomas had brought sufficient clothes that he could change them regularly, but that meant that he was carrying twice the load of the rest of us.

With my superior insight into such matters, I realised that, unlike the Arctic or the African jungles, the Lake District is not isolated from our wonderful Post Office. So, beforehand, I had parcelled to myself at the Fish Hotel a complete change of clothes for the rest of our walk. I spent a pleasant evening parcelling up my dirty clothes to send home whilst the others scrubbed the mud of Buttermere Moss off theirs.

Photos: Potted Char and Other Delicacies; Derwent Water from the slopes of Catbells; The view from my window at the Fish Hotel.

A Word’s Worth

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: I don’t mind if I do. Thank you, Ernest.Ernest Ackland (Privy Councillor, Master of the Toilet Rolls): Jack, my good man, top us up if you would be so kind.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Now, Ernest, do you know that railway over Ravenglass way?

Ernest Ackland: Yes, I believe so. I took my grandson there last summer.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Do you remember the name?

Ernest Ackland: Joseph, Joshua, something like that.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: No, not the lad. The train.

Ernest Ackland: Oh. Ah. Something a bit rum. Real Tatty. Something like that.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Jack will know. He’s lived here all his life. Jack, what do you call that railway over at Ravenglass?

Jack (barman of the Crowing Cockerel): La’al Ratty.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Could you spell that please?

Jack: L A A L and R A T T Y.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: You sure about that?

Jack: No, not really. We say the words. We don’t need to spell ’em.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Could there be an apostrophe in laal? L A apostrophe A L?

Jack: Could be. Yes, now you mention it, yes, I think there is.

Ernest Ackland: If there’s an apostrophe it must stand for something left out. What could that possibly be?

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: ckadaisic perhaps. Anyway, it doesn’t matter, as long as there’s an apostrophe. And you think there is, Jack?

Jack: Yep, think so.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Splendid! Serve the bounder right!

Ernest Ackland: What are you talking about, George?

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Well, you know my good woman runs the guest house. I told her when I retired up here that if she wanted a guest house to keep herself amused then it would be entirely up to her. I’d help spread some bonhomie in the bar but apart from that I haven’t got the time for that sort of people.

Ernest Ackland: Quite right too.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: To tell the truth, I don’t know how she manages to pass the time: a spot of cooking, a bit of cleaning, a smidgin of finances, a smattering of general repairs. I left her up on the roof this morning. Anyway, it gives her a purpose in life.

Ernest Ackland: Yes, that’s always important for a woman.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: But sometimes, when I get back at night, she looks quite fatigued, as attractive as soldiers’ pants after a long march. I don’t impose upon her on such occasions, and I’m sure she appreciates that.

Ernest Ackland: I know what you mean.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Unfortunately, she has bright ideas from time to time. She thought ‘themed weeks’ were the current fashion and so for last week she organised a ‘Scrabble Week’.

Ernest Ackland: I wouldn’t have thought that would appeal much.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: You’d be surprised. I asked them in the bar and they said that they normally come to the Lakes with the intention of taking lots of invigorating walks but it always rains so much that they end up playing lots of scrabble. So this time they reckoned that if they came intending to play lots of scrabble then it would be fine and sunny so they could go on lots of invigorating walks.

Ernest Ackland: And was it?

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: No. Anyway, having had the bright idea, my good woman then considered that she is too busy doing whatever she does all day so she asked me to be referee. Well, if I say so myself, my military bearing rather suits the role of referee, so I agreed as long as I could referee in the bar and await any disputes, which I didn’t expect as most of them were dear old ladies.

Ernest Ackland: I bet they were fierce scrabblers, though.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Well, yes. Vicious. And then my good woman had another bright idea: to add a little local flavour to the event, she defined a Cumbrian variant, by adding a rule that any word of the Cumbrian dialect would score quadruple points. Now, a chap called Seamus Donnybrook wasn’t happy with this ...

Ernest Ackland: Donnybrook? Wasn’t he the fellow we had to have evicted from the golf course?

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: The very same. He got more and more annoyed at all these sweet biddies getting extra points for ‘snig’, ‘radge’, ‘glisky’, and so on. I had to leave the bar to see what all the kerfuffle was about. We generously allowed him Irish words such as ‘colcannon’ and ‘hooley’ provided they were in our dictionary, but of course he didn’t get quadruple points for them. Suddenly, he jumped up, shouting “Got you, you cheating witches: laal - four, triple word, quadrupled, 48 points. Stuff that in your cauldrons”.

Ernest Ackland: Ah.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Well, dear Marjorie Primps quietly said “Rule 8 - no words with apostrophes”. You should have heard him. His words may be in the dictionary but I don’t think you’d dare use them at scrabble with these dear ladies. Now, I had no idea if laal had an apostrophe or not, but I didn’t like the cut of his jib, so I turfed him out.

Ernest Ackland: Not before time, from the sound of it.

Major Dalbeigh-Smythe: Top up, Ernest?

Ernest Ackland: I don’t mind if I do.

Photo: The staff at Ravenglass railway station.

One Fell Swoop

This extract from the recently-published memoirs of the celebrated Cumbrian climber Stanley J. Accrington describes the first solo ascent of Helvellyn by the western arête (well, the first solo ascent by Stanley J. Accrington anyway). I slept intermittently. Visions of the impending peril infiltrated

my unconscious. I looked at my watch. 3.48! In the morning.

With that fortitude for which British mountaineers are renowned, I

forced myself to lie slumbering in bed for a few more hours until I

sensed the aroma of sizzling bacon.

I slept intermittently. Visions of the impending peril infiltrated

my unconscious. I looked at my watch. 3.48! In the morning.

With that fortitude for which British mountaineers are renowned, I

forced myself to lie slumbering in bed for a few more hours until I

sensed the aroma of sizzling bacon.

Outside, the wind raged ferociously. I would need every item of warm clothing that I had, plus any I could purloin. I carefully calculated the minimum provisions required for the expedition: mint cake, energy bars, a tin of apricots, lemon juice, water, plus a small bottle of spumante, just in case fortune should enable me to celebrate reaching the summit.

Breakfast over and the necessary ablutions performed, I braved the wind which was still blowing hard. Delay would only reduce the hours of daylight available. Leaving base camp I tramped slowly up the long lower slopes to reach the great ‘hole-in-the-wall’ by midday. Here were scattered the remains of previous expeditions, with echoes of earlier failures adding an air of desolation. But it provided a wonderful prospect of the fearsome arête ahead.

I continued on up the ridge, taking it slowly and steadily, because of my great burden and the reduced oxygen. I appreciated the mountaineers’ whimsy in calling this arête Striding Edge, for striding is one thing you cannot do upon it. I was beginning to tire and looked around for a suitable lunch-time ledge, but there was none. Somewhat desperate, I traversed across the steep slope on the sheltered side to find eventually a relatively flat spot overlooking Red Tarn far below.

Well satisfied with lunch and the height already gained, I

pressed on. Vertiginous slopes plunged down on both sides of

the knife edge, slopes down which, sadly, many less competent

mountaineers have also plunged.

The altitude and wind took my breath away, the latter

occasionally upsetting my balance and my morale. After some

determined scrambling, I reached an awkward rock chimney,

beyond which I could see the arête rising yet more steeply.

Well satisfied with lunch and the height already gained, I

pressed on. Vertiginous slopes plunged down on both sides of

the knife edge, slopes down which, sadly, many less competent

mountaineers have also plunged.

The altitude and wind took my breath away, the latter

occasionally upsetting my balance and my morale. After some

determined scrambling, I reached an awkward rock chimney,

beyond which I could see the arête rising yet more steeply.

As all responsible mountaineers must do from time to time, I considered the advisability of carrying on. It is unwise to mountaineer alone and on those occasions when I cannot avoid it I invent a companion, whom I call YetI. As a team, I and YetI can climb higher and yet-higher. YetI is an extension of myself: wise, brave, athletic, charming, and with all his own teeth - like myself, only more so. The ideal companion. I asked YetI about the wisdom of continuing and he replied, as he always did, “Just as you wish”. I decided to go on.

I focussed my attention on the rock chimney, the notorious step that often made the difference between success and failure. No doubt, it would be a minor problem to expert rock climbers on Everest but here it was a barrier that needed all my considerable strength and will-power to overcome. With fervent prayers that the rocks I grappled with would stay attached to the mountain, I inched myself along, finally dragging myself onto a ledge, where I lay for a while regaining my breath and composure.

But now the challenge of the steeper slope became apparent. At first glance it was impressive and rather frightening, even to a man of my self-effacing courage. We checked our provisions, our bearing, and our sanity and, finding all sufficiently in order, carried on. The ridge was narrow and difficult, made even more so by the many mountaineers passing in the opposite direction.

At this point, I have a suggestion for the authorities. You should not allow so many inexperienced mountaineers to wander about at will. Insist that they ascend this arête only on odd days of the month and descend it only on even days, and obviously vice versa for other arêtes. Problem solved. I often find that I have solved many of life’s major problems during expeditions such as this.

We climbed slowly, but safely, which was the main consideration. Steep rock slopes arose ahead of us. It was tempting to seek an easier way to the side, but that way disaster lay. Time was passing and the cliff seemed never-ending. Our original energy had long gone and it was now a grim struggle. We rested every fifteen minutes to regain our breath and a little vigour.

And then suddenly there was grey sky rather than black rock ahead. We had reached the end of the arête, and there, curving to the right, was a more gentle slope leading to the summit, our Shangri-la (Editor: isn’t that a valley?). Finding extra reserves of energy, we staggered to the top. My initial feelings were of relief, rather than triumph.

But then the realisation of what we had achieved sunk in. Somehow, I shook YetI’s hand vigorously and slapped him on the back. We sipped the spumante. I surveyed all around, to the great peaks surrounding us and down into the far-off valleys, where dull people were going about their dull routines. I couldn’t wait to get back to impress them with the life-enhancing insights gained on an expedition such as this. I asked YetI if he was ready to descend. “Just as you wish” he said.

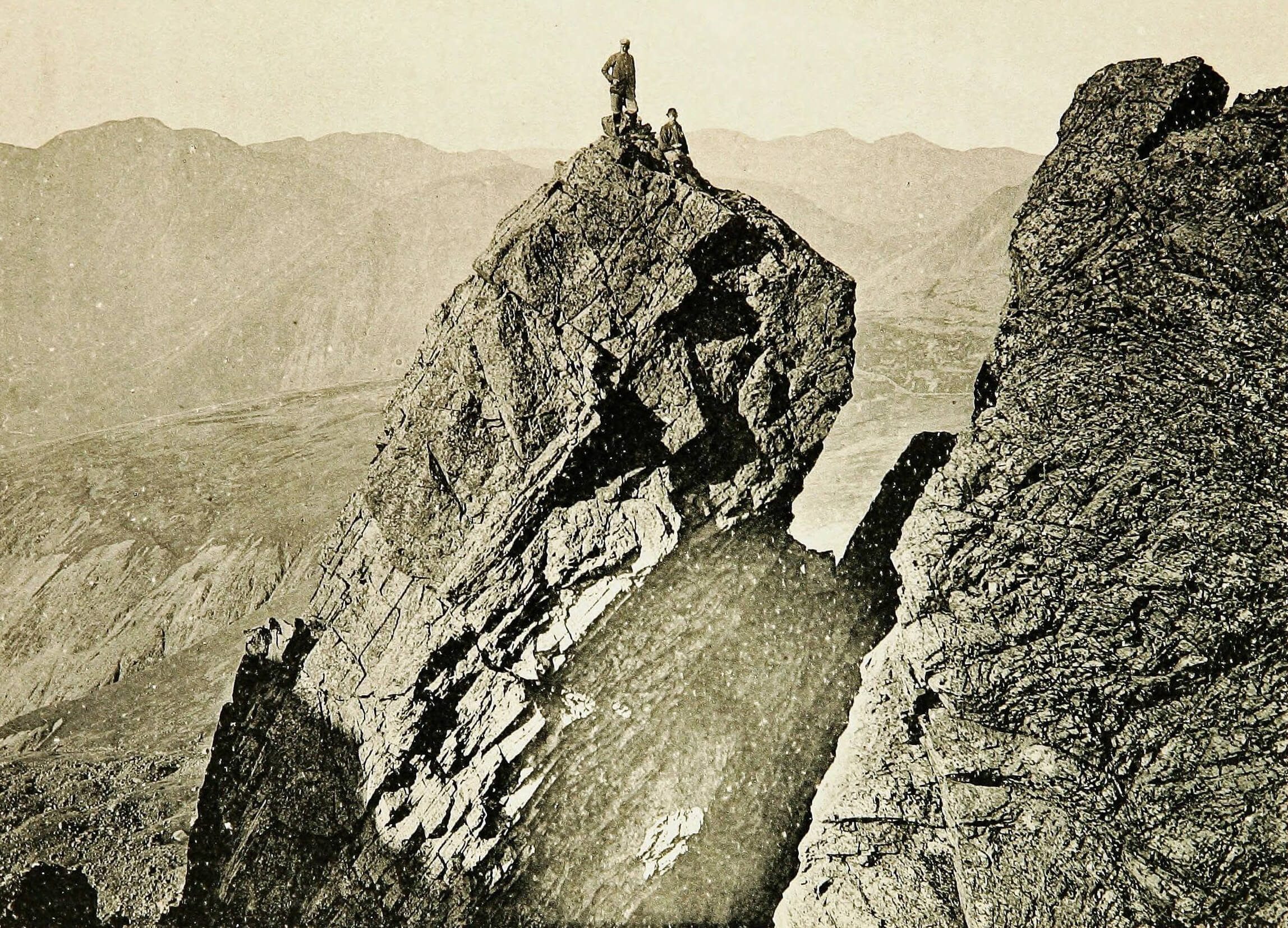

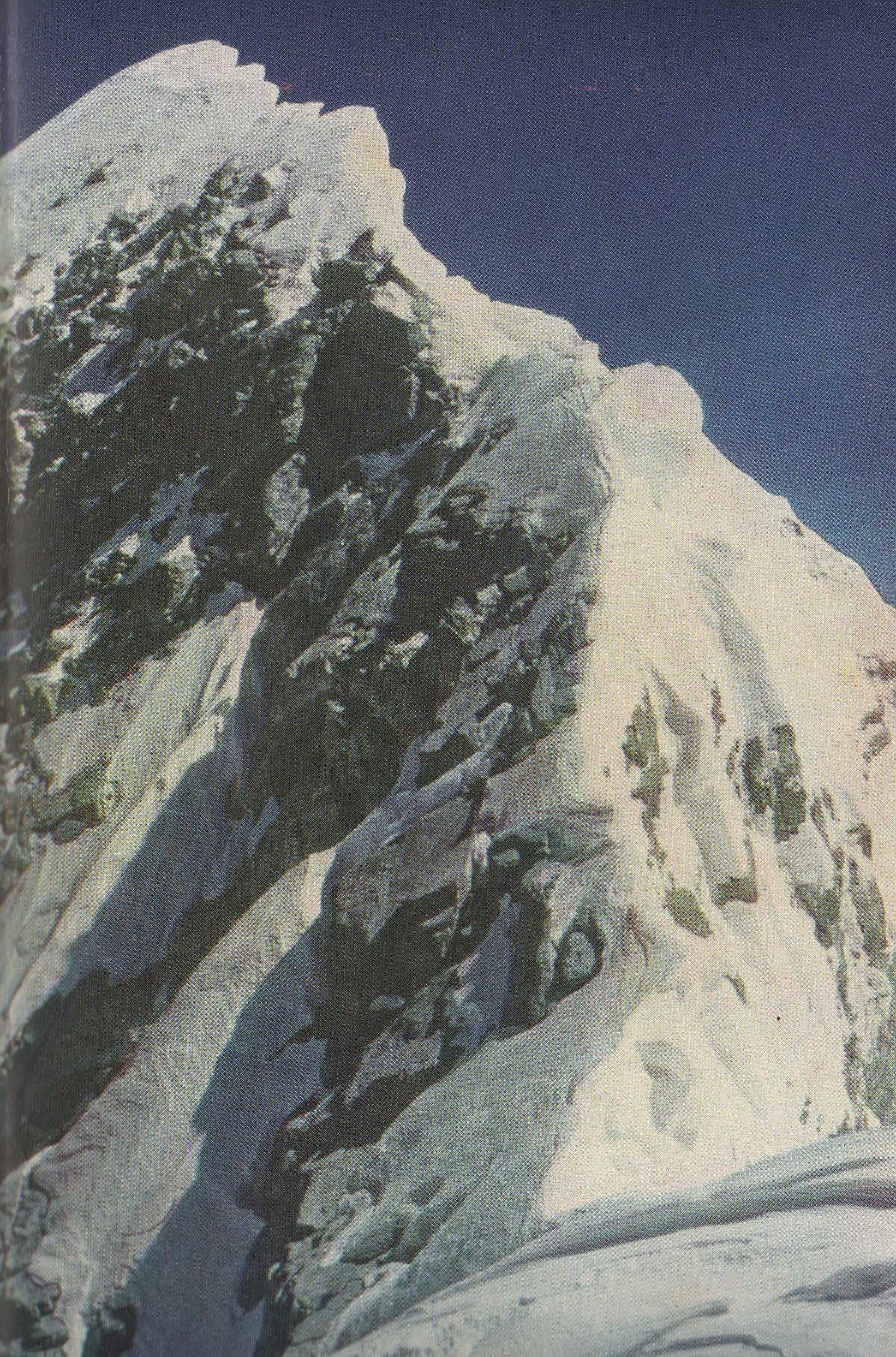

Photos: Stanley J. Accrington in his prime, on Scafell Pinnacle; Helvellyn’s western arête.

Four Men in Their Boots, Day 9

... Buttermere ...

We departed from the Fish Hotel in good spirits, all of which belonged to me, freshly attired as I was. As we peered across the choppy lake towards the steep slope of Fleetwith Pike, it was apparent that this was a day for which the word changeable would be an understatement. Patches of cloud were being whipped across the tops, with the gaps between the clouds enabling the sun to highlight islands of bright green, which likewise tore across the hill-sides. The clouds themselves released whirling rain-storms enlivened by temporary rainbow colours. We strode along the well-worn path through Burtness

Wood towards Bleaberry Tarn. In the sun the ridge up to Red

Pike did indeed look red; in the cloud, it didn’t. As we crested

the top of Red Pike we were engulfed in what I suspected

would be the first of many rain clouds. We hurriedly donned

our wet-weather gear and continued briskly along the broad

ridge to High Stile and High Crag.

We strode along the well-worn path through Burtness

Wood towards Bleaberry Tarn. In the sun the ridge up to Red

Pike did indeed look red; in the cloud, it didn’t. As we crested

the top of Red Pike we were engulfed in what I suspected

would be the first of many rain clouds. We hurriedly donned

our wet-weather gear and continued briskly along the broad

ridge to High Stile and High Crag.

Every few minutes the clouds parted to give us tantalising glimpses down the excitingly precipitous crags towards the village and the lake of Buttermere. In the other direction, our future targets of Pillar and Scafell made fleeting appearances. Somehow, the ephemeral nature of the view enhanced its appeal. We knew that if we didn’t appreciate it whilst we had the chance we might not get another one.

We scrambled down the unpleasant scree to Scarth Gap and on towards Ennerdale Forest, which was, at last, being allowed to revert to natural woodland. Arriving at the Black Sail Hut, we found large numbers of people gathered, preparing to set off on their hike, obviously after a more leisurely start to the day than my well-trained team had managed.

Again, many of them seemed to know Harry, who was soon acknowledging their best wishes and shaking hands with all and sundry. With a nod towards me, one of them shouted “Ist dat mein führer?”, or something similar, to the merriment of everybody. It was rather perplexing but it seemed good-natured enough, so I waved, rather stiffly, in acknowledgement, which provoked further gales of laughter.

... Great Gable ...

Eventually, I was able to drag Harry away. We needed to focus on what I knew would be one of our most challenging climbs - that up Great Gable from Beckhead Tarn. I had intended to take us up Kirk Fell en route to Beck Head but, after our long delay at the hut, I decided to be less demanding of my colleagues. Instead, I took us along the contour below Boat How Crags.There was, however, no way to avoid the rough, steep slope of great boulders on the northwest flank of Great Gable. Here, unfortunately, the cloud settled in, making it difficult to determine the way ahead. After the misadventure on Hart Crag, I kept the team closely together. This was not terrain in which to let anyone get lost, or to have to search for them.

We paused at the top of Great Gable to pay our respects to those named on the plaque as having died in the 1914-18 war. A ceremony every November does likewise. It felt incumbent upon me to lead a small service and, taking Genesis 22 as my text, I extemporised a sermon about Abraham taking his son up a mountain in Moriah for a burnt offering.

Other hardy souls arrived at the top and they too

gathered around. As the fate of Abraham’s son seemed

to depress them, I moved on to Exodus 3, where Moses is

entreated by God to climb the mountain over and over. This

prospect did not enthrall the assembled throng much either.

So, with the congregation now nearing a hundred or so, I

turned to Luke 9, where Jesus and his disciples take to the

mountain. “While he thus spake, there came a cloud, and

overshadowed them: and they feared as they entered the

cloud.” This, at last, they could relate to, and thus uplifted the

multitude dispersed.

Other hardy souls arrived at the top and they too

gathered around. As the fate of Abraham’s son seemed

to depress them, I moved on to Exodus 3, where Moses is

entreated by God to climb the mountain over and over. This

prospect did not enthrall the assembled throng much either.

So, with the congregation now nearing a hundred or so, I

turned to Luke 9, where Jesus and his disciples take to the

mountain. “While he thus spake, there came a cloud, and

overshadowed them: and they feared as they entered the

cloud.” This, at last, they could relate to, and thus uplifted the

multitude dispersed.

... Green Gable ...

We solemnly made our way down the remains of the path towards Windy Gap and up Green Gable, the insignificant sibling of Great Gable. Again, the top was in cloud and as we wandered about trying to locate the topmost point, a strange vision appeared before us. A young couple, clad only in sandals, shorts and tee-shirts, emerged from the mist. They seemed in high spirits, oblivious of the wet clouds scuttling past them. I couldn’t at first understand a word they said but with Harry’s careful interpretation it turned out that they were asking if this was Great Gable.I do despair, sometimes. I have no time for those who set out to walk in the Lake District completely unprepared for the difficulties that they may face. And when they don’t even know where they are, I give up. Harry, however, took them under his wing. He asked to see their map, presumably so that he could point out where they actually were. I was no longer taking any interest but I saw that they produced from a pocket a scrappy piece of paper with only a few tops marked and some dotted lines between them, with no indication of contours, cliffs or anything else. They did not know what a compass was, let alone possess one.

With great solicitude, Harry explained where they had arrived and elucidated from them where they hoped to go - on up to Great Gable, down the treacherous ridge that we had struggled up, and then along Moses Trod back to Honister. He also discovered that they were from Holland, which may explain their limited knowledge of mountain walking. And that they were on honeymoon, which may explain their limited interest in anything except one another.

Harry, fearful that their marriage, or even themselves, might not survive an expedition up Great Gable in these conditions, wearing so little, began to describe the fearsome, dangerous mountain ahead of them. They couldn’t see the mountain, of course, but could only listen in astonishment at the alarming ordeal ahead of them, as described in the most vivid, eloquent fashion by Harry. After several minutes of this, they began to think, as Harry intended, that perhaps it would be better if they returned safely the way that they had come. Once they had persuaded themselves, Harry gallantly volunteered to escort them back.

The others were also, by this stage, becoming quite fond of these foolish Dutch youngsters. Richard said that he’d go along with them too, ostensibly to keep Harry company. Thomas seemed about to join them but he thought better of it once I made it clear that the maps stayed with me. If others chose to depart from my ordained route without permission that is up to them. It is not my responsibility to look after all the waifs and strays that one encounters on the Lake District hills. I’d feel like the Pied Piper of Hamelin if that were the case.

Thomas and I walked down to Seathwaite in silence, entranced by the transitory glimpses of sun in the valley. Predictably, the others were late to meet us in Seatoller, having become lost on Brandreth.

Photos: Buttermere; The Great Gable memorial service.

Border Conflicts

From a Cumbria Council MeetingDiana Dubble-Barrell (chair): Our good friend Charles Smarm, the head of Cumbria Tourism Services, joins us again for the next item. Would you like to introduce the discussion document that you kindly prepared for us, Charles?

Charles Smarm: With the greatest pleasure, Diana. My guiding principle is that in these difficult economic times we must all pull in the same direction, and that is to make Cumbria the number one tourist attraction in Europe, if not the world. That is the most important thing, the thing to which all our efforts should be focussed.

Joss Jenkinson (Cartmel ward): Not sure that we farmers would agree with that.

Diana Dubble-Barrell: Please. Let Charles finish.

Charles Smarm: It’s ok, Diana. I appreciate that point of view. The punters like to see a few sheep in the landscape. And the odd yokel leaning over a farm-gate is always welcome. Now, I don’t intend to go through the detail of my document, as I’m sure that you’ve all read it thoroughly, but I’d be very happy to answer your questions.

Josh Jenkinson: Excuse me, everybody, but I’ve just remembered that I have some yokelling to do.

Harry Cowan (Furness ward): Mr Smarm, I see that you say that we should, wherever possible, emphasise Cumbrian products. Could you give some examples?

Charles Smarm: Certainly. I think, for example, that we should pass a by-law that says that all sausages to be sold in Cumbria must be Cumberland sausages.

Harry Cowan: Rather difficult to enforce, don’t you think?

Charles Smarm: Not at all. We could employ an army of inspectors to tour butchers, hotels and restaurants, tasting sausages to see if they cut the mustard.

Harry Cowan: I wouldn’t mind that job. Any other examples?

Charles Smarm: Erm. How about: all cakes sold in Cumbria must be Kendal mint cakes.

Harry Cowan: Kendal mint cake isn’t a cake.

Charles Smarm: Isn’t it? What is it, then? We mustn’t leave ourselves open to accusations of misleading the punters.

Harry Cowan: Haven’t you tried it?

Charles Smarm: I’m afraid that I haven’t been to the Kendal Mint yet.

Margaret Tyson (Grayrigg ward):

Um. Excuse me. Your document makes some oblique comments

about those of us on the fringes of Cumbria. What do you have

in mind?

Margaret Tyson (Grayrigg ward):

Um. Excuse me. Your document makes some oblique comments

about those of us on the fringes of Cumbria. What do you have

in mind?

Charles Smarm: Well, if Manchester City were to acquire John Terry from Chelsea they would expect 100% allegiance from him. They would not expect him to keep going on about the delights of Stamford Bridge.

Margaret Tyson: Eh? Terry who?

Charles Smarm: Please let me explain. For example, I notice that in Sedbergh there is a popular hostelry called The Dalesman. Now, Sedbergh has been in Cumbria for over thirty years. It is high time that it stopped referring to the Yorkshire Dales. The inn should be renamed as The Lakesman. And the Tourist Information Centre there should only have books about Cumbria. And ...

Margaret Tyson: Hold on a minute. Sedbergh is still in the Yorkshire Dales.

Charles Smarm: Be that as it may, Sedbergh is within the District Council of Cumbria. It receives its funding from here. It should therefore give total allegiance to Cumbria. In these times of limited funding, the Council should prioritise those areas that fully support Cumbria.

Dick Howarth (Kirkby Lonsdale ward): That sounds like a threat to me. In Kirkby Lonsdale we are closer to the Yorkshire Dales National Park than we are to the Lake District National Park. And we are right next to the Lancashire border too. Some of my best friends are from Lancashire and Yorkshire. Are you saying that when we have visitors to Kirkby Lonsdale we should direct them all to the Lake District?

Charles Smarm: Exactly. That is precisely what I mean.

Dick Howarth: You blithering oaf. I bet there aren’t many Smarms in our telephone directory. Not exactly a local, are you? Some of us have lived here for centuries. It’s only a few months since you came here from the Norfolk Broads. What the hell do you know about our priorities?

Charles Smarm: Don’t you start ...

Diana Dubble-Barrell: Gentlemen, please. A good time for a tea break, I think. But without any of that Kendal mint cake.

Photos: The Dalesman; Sedbergh (Cumbria), with its Yorkshire Dales sign.

Fell-Walking Tip 15

According to a recent medical study reported in the International

Journal of Peripatetic Osteopathy, people who are unaccustomed

to fell-walking and who spend two weeks clambering up high

mountains carrying a heavy backpack lose, on average, 11cm (over

4 inches) of height.

According to a recent medical study reported in the International

Journal of Peripatetic Osteopathy, people who are unaccustomed

to fell-walking and who spend two weeks clambering up high

mountains carrying a heavy backpack lose, on average, 11cm (over

4 inches) of height.

This is because the intercostal muscles of people unused to pedestrianism with a vertical dimension are, in precise medical terminology, flabby. They collapse under the extra strain - the muscles, that is, and the people too, sometimes.

To prevent this, novice fell-walkers are recommended to pause after one hour of walking and to lie for two minutes on a gentle downward slope, head downhill, so that gravity may restore the spine and ribs to their original shape.

It is not advisable to lie for more than two minutes otherwise the blood will run to the head causing even more serious problems. Or you may just fall asleep, which is not the purpose of a fell-walk at all.

The optimum degree of slope is between 5 and 10 degrees. On no account lie on a slope of greater than 15 degrees. If you do, you may slide head-first off the mountain and this is, generally speaking, a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

Photo: A demonstration of the recovery position.

A Week in the Lake District

Saturday: All arrived by half-six. Some misunderstanding about who was invited. I’d booked the cottage for the five of us, to celebrate ten years since graduating. But Charles brought Annie and Richard Tara. We’d all not met since Charles’ third marriage (to Fiona, I think it was). Drinking, chatting, late night.Sunday: Late breakfast. Light rain. Gentle stroll up Cat Bells to loosen up. All in good spirits. Particularly lively between Richard and Tara at the back. Heard a cuckoo. Small blister on the right big toe.

Monday: Showery. Charles, Malcolm, Peter, Annie, Richard and I walked up Skiddaw. Tara opted out (didn’t sleep well; Richard slept in lounge, I think). Could have been a wheatear. Blister made walking uncomfortable - now have a sore knee.

Tuesday: Low cloud. Malcolm, Peter, Annie, Richard and I conquered Great Gable. Charles didn’t think it right to leave Tara on her own. Very chivalrous of him. Lost Malcolm and Peter for a while in the cloud. Saw a woodpecker in Seathwaite. Both knees painful now.

Wednesday: Very windy. Charles slept in the kitchen, I think. Peter, Annie, Richard and I walked up Loughrigg - an easy walk, because of my knees. Tripped over a rock, injuring my hip. Peter rather morose. Malcolm had stayed in the cottage: ‘personal things’ to sort out, he said. Pied flycatchers by the lake.

Thursday: Squally showers. Peter stayed to help Malcolm with his problems. Annie, Richard and I did the Buttermere Horseshoe. They strode ahead; I hobbled behind. A couple of times they forgot about me. Watched ring ouzels on Brandreth. Had a tumble on Haystacks: dislocated shoulder.

Friday: Steady rain. Nobody slept in the lounge or kitchen, I think. Annie said she was too tired to walk today. Richard and I tackled Helvellyn. He talked of Annie the whole way. Four buzzards above. The walk was a bit bold, with my injuries, but I thought “last day, go for it”. Fell off Swirral Edge. The Rescue Service wasn’t long.

Saturday: Sunny. Charles and Tara, Malcolm and Peter, Richard and Annie had separate walks up Cat Bells. Watched a great tit on the bird table. “Must make it an annual event” they said. Nobody offered me a lift home.

Many Happy Returns to Bassenthwaite

“Nearly there, at last. Soon we’ll have to make our big decision, my turtle dove”.“I’ve told you: I’ve already made it. I’m not going there again. And I’m not your turtle dove”.

“But why? What’s wrong with the old place? They always look after it so well for us. Any spot of damage in the winter and they’re up straightaway to repair it”.

“Typical. You’re just too lazy to repair it yourself, like all the others do”.

“But they’ll be so disappointed. They look forward so much to us turning up”.

“That’s their problem. They should have better things to do”.

“But my previous bird liked the place. Seven years in a row we

went there. Never a peep of complaint from her”.

“But my previous bird liked the place. Seven years in a row we

went there. Never a peep of complaint from her”.

“Your previous bird can get stuffed. I make the decisions now. And I’m not going there again”.

“But it’s always so tidy. All mod cons. Lovely view. Why don’t you like it?”

“Well, for a start, I don’t like all the cameras. No privacy at all. Every second of the day they’re watching and analysing everything I do. It gets on my nerves”.

“Oh, come on, you’re exaggerating”.

“It’s all right for you. You’re off gallivanting about most of the time”.

“Hardly gallivanting. I keep you well supplied, don’t I? Anyway, that’s part of the deal: they look after us and we entertain them”.

“You can entertain them if you like. I’ve got more important things to do”.

“Well, I enjoy it. Do you remember that time when I circled round and round them so much that they became too dizzy to stand?”

“Yes, served them right”.

“And last year when I ‘accidentally’ dropped that trout on them?”

“Even better”.

“Anyway, I can see the place coming up now. So, what are we going to do?”

“Well, I’m not going there, that’s for sure”.

“OK, then, if you insist. You’re the boss. On to Scotland it is”.

“Scotland? Who said anything about Scotland? There’s too many of us up there already. I’d rather be somewhere near here, on our own. Quiet and peaceful”.

“Ah. Well, in that case, how about a starter home on the other side of the lake?”

“Starter home?”

“Yes, they built a few of them last year, hoping to attract some first-time fliers”.

“What? Aren’t we good enough for them? What a cheek! I’ve a good mind to teach them a lesson”.

“How do you mean?”

“Well, let’s go to the old place and get them all a-twitching. And while they’re dashing about with their binoculars and cameras, we can sneak off in the dark to one of the new places. Then we can have weeks of fun watching them getting in a muddle, trying to find out where we’ve gone, working out how to put up some new cameras, making new viewing points, and all that palaver”.

“And I can still drop trout on them?”

“Certainly. And next year we can do it all again, and the year after, and so on”.

Four Men in Their Boots, Day 10

... Seatoller ...

This, we knew, would be a day to savour! - the kind of Lake District day that we dream about. Not only would we climb to the highest point of England but, as we set off from Seatoller, we could see that we would be blessed with one of those bright, perfectly clear days that we always hope for but are rarely given.Rather than tramp along the familiar valley through Seathwaite, I led the team up through the wood and on to Thornythwaite Fell. Seathwaite is the wettest inhabited place in England (140 inches a year) but I had no fear of rain on such a day. I just felt that the sooner we were on the tops and able to enjoy the fabulous views the happier we would be. And so it proved.

... Glaramara ...

Glaramara is described as a long, sprawling, heavy, plum-coloured hump in the Herries Chronicles of Hugh Walpole. But the name is irresistible. It is a mountain that just has to be climbed. We paused at the higher of the two summits of Glaramara to take in the view, perhaps the best from any Lake District top, with its central position and relatively modest height providing a 360-degree panorama of higher fells: to the east, the Helvellyn ridge, with High Street in the distance; to the north, Derwentwater with Skiddaw and Blencathra beyond; to the west, a fine prospect of Green Gable and Great Gable, where conditions had been so different yesterday - all terrain that we had already conquered, as we proudly reflected.Then our eyes turned south to peaks still to be tackled: Coniston Old Man, Crinkle Crags, Bowfell. But could we see our main target for today, Scafell Pike? We didn’t argue - but we couldn’t agree. It seemed to me that the great buttresses of Ill Crag and Great End obscured the very top of Scafell Pike but it was hard to be sure.

So, although it would have been very pleasant to stay a few hours debating the matter and absorbing the multi-faceted view in all its glory, we set off to investigate. We walked south along one of the most delightful ridges in the Lake District, with a succession of neat little tarns tucked into grassy depressions below minor stony peaks, all the while surrounded by the evolving panorama.

We paused again when we reached the summit of Allen Crags, still entranced by the views. Helvellyn, Skiddaw and Great Gable could still be seen, the last boldly portrayed behind the most attractively-named Lakeland tarn, Sprinkling Tarn. The visibility was so good that it was easy to pick out on the flank of Great Gable the silhouette of the famous Napes Needle. To the south and west the forbidding prospects of Great End and Ill Crag confronted us, now undoubtedly obscuring the Scafell Pike peak. We lingered for quite a while at the Allen Crags haven as we surveyed below us a series of walkers toiling up the thoroughfare towards Esk Hause and on to Scafell Pike.

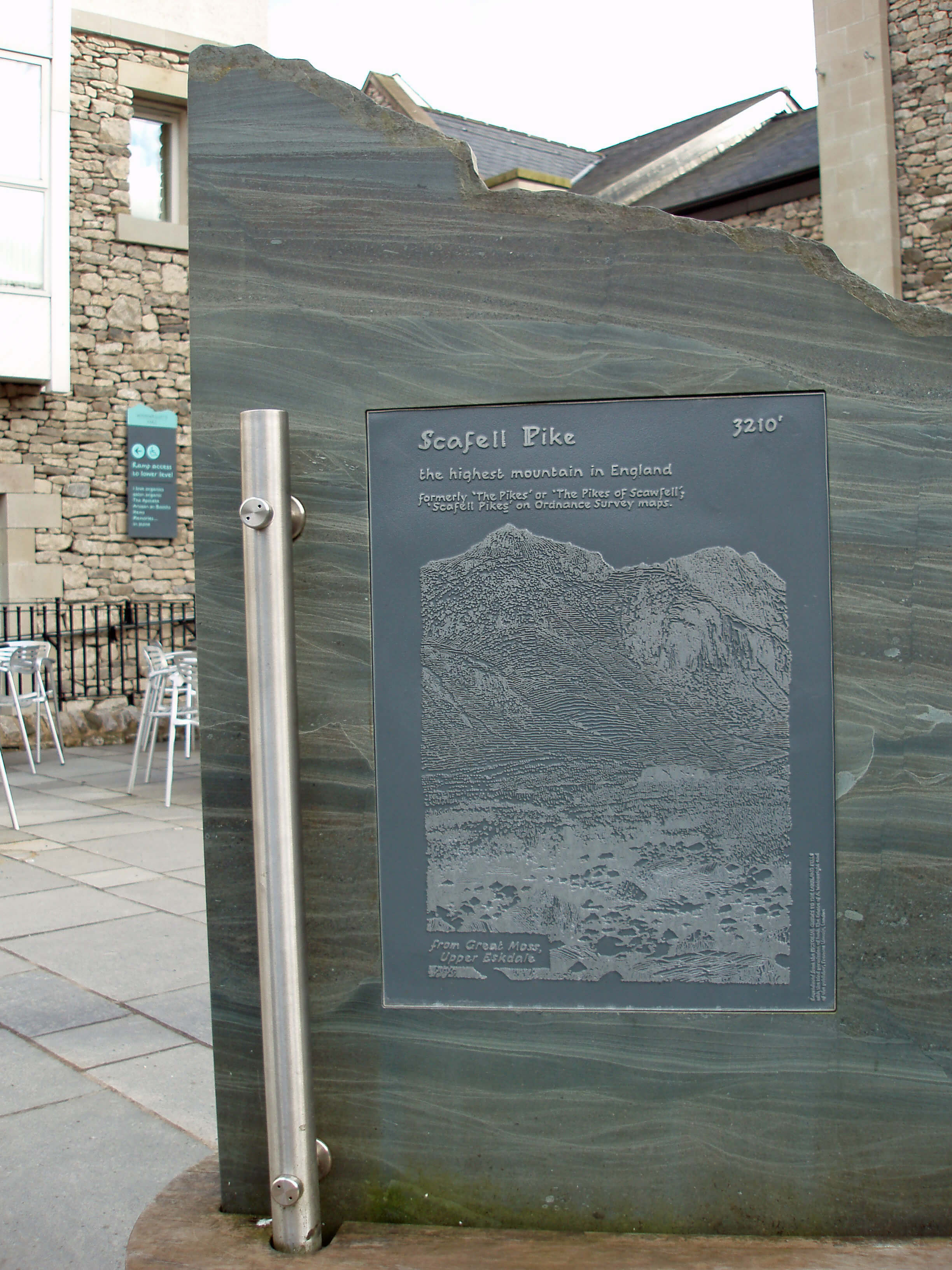

... Scafell Pike ...

Eventually, we accepted that it was time for us to do the same. We scrambled down the southern slope and up to Esk Hause, one of the busiest crossroads in the Lake District. Following the multitude heading south-west, we skirted Ill Crag, where at last the summit of Scafell Pike came definitely into view, still some distance away but, on a day such as this, presenting little difficulty. I briefly delayed the exhilaration of conquering England’s

highest summit by leading the team off the standard route to

cross the rough jumble of rocks on Broad Crag in order to take

in the view, which could never be better than it was today,

from a northern perch, looking across to Great Gable.

Now, the climactic moment could be postponed no longer.

We jubilantly reached the huge circular cairn that makes the

highest point of England yet higher. Needless to say, the view

was all-encompassing. We looked down upon previously-majestic heights - except perhaps to the south where Scafell

looked as high (but we’d worry about that later).

I briefly delayed the exhilaration of conquering England’s

highest summit by leading the team off the standard route to

cross the rough jumble of rocks on Broad Crag in order to take

in the view, which could never be better than it was today,

from a northern perch, looking across to Great Gable.

Now, the climactic moment could be postponed no longer.

We jubilantly reached the huge circular cairn that makes the

highest point of England yet higher. Needless to say, the view

was all-encompassing. We looked down upon previously-majestic heights - except perhaps to the south where Scafell

looked as high (but we’d worry about that later).

So, this unforgettable day was all but over. It was all downhill from here. We headed towards Lingmell and down by Lingmell Gill to Wasdale, content that, whatever adventures the days ahead held, the walk to Scafell Pike had been perfection.

... Wasdale Head ...

After a convivial repast at Wasdale Head I expected to sleep

the sleep of the fully contented. But it was not to be. I was

tormented by a dreadful nightmare. I dreamt that I was

awoken by a fearful wailing and shouting outside.

In my dream, I gave up trying to sleep through this

terrible noise and peered out of the window. It was a clear,

cloudless, moonlit night but I could see nothing, at first. But

then I made out a light moving on the slopes of Scafell Pike,

and then several of them, some moving up, some down. And

over on Lingmell I could see yet more lights moving about, all

to the accompaniment of diabolical yelling.

After a convivial repast at Wasdale Head I expected to sleep

the sleep of the fully contented. But it was not to be. I was

tormented by a dreadful nightmare. I dreamt that I was

awoken by a fearful wailing and shouting outside.

In my dream, I gave up trying to sleep through this

terrible noise and peered out of the window. It was a clear,

cloudless, moonlit night but I could see nothing, at first. But

then I made out a light moving on the slopes of Scafell Pike,

and then several of them, some moving up, some down. And

over on Lingmell I could see yet more lights moving about, all

to the accompaniment of diabolical yelling.

What was going on? Why were so many people up on the hills at night? Was it a search party? Had there been some catastrophe on the fells? Had a plane crashed perhaps?

In the dream I felt compelled to awaken my colleagues. We surely needed to do something to help. My team could make no sense of it either but, on balance, preferred to return to bed. I would not let them, however, and dragged them along to awaken the hotel owner to call the emergency services.

He had the briefest glance out of the window, and said “*!!*%£!* three-peakers”. Harry realised what he meant. It seems that every night of summer people attempt to raise money for charity by climbing the three peaks (Ben Nevis, Scafell Pike, Snowdon) within 24 hours. Being the middle of the three, Scafell Pike is usually tackled at night.

“It shouldn’t be allowed” I said “making such a racket in the middle of the night. Selfish buggers.”

“But it’s in a good cause” Harry replied. “They’re doing nobody any harm. It’s a tough challenge they’ve taken on.”

I tossed and turned in my bed as I argued this out with Harry. During this nightmare Harry made the startling revelation that he himself was, in fact, using this two-week Lake District expedition as a sponsored walk. What a liberty! How could Harry let me put all the work into arranging this trek and then secretly support a charity that I might not even approve of. Richard and Thomas were none too happy either.

It is strange how a dream can make sense of odd events during the day. It explained why Harry ‘hopped behind a rock’ every few hundred yards. He was not responding to excessively frequent calls of nature. He was creating calls of his own, ‘tweets’ I believe they’re called, to his many ‘followers’. He had thousands of them, he said. They were tracking his progress on the fells, literally in many cases, it seemed, judging from all the apparent friends we met. So that’s why he wore such a uniquely colourful outfit - in order to be easily recognisable. He even admitted that in his tweets he refers to me as ‘mein führer’.

In real life I am, of course, a man of the most equable temperament. I cannot understand those people who, at the mildest - or even the severest - provocation, resort to violence. There is no disagreement that cannot be resolved by reasonable discussion, I always say. But in a dream our inhibitions are loosened. Mine are, at least. I punched Harry. Hard. On the nose. Twice.

At all events, that is how I remembered the dream when I awoke too early after an unpleasantly fitful night’s sleep.

Photos: The rest of the crowd on the Scafell Pike cairn did not admire the view but spent their time consulting their technology to check that they were indeed on the top of Scafell Pike; Wasdale Head Inn.

At Your Beck and Fell

Cumbrian Mountain Service: Executive Directors’ Annual ReportThis has been a very successful and profitable year for the CMS. The number of incidents was 1834, up 285% on the previous year, with the number of injuries or deaths down to 0, a decrease of 100%. The number of person-hours spent on incidents was 36,355 (up 47%) but the welfare of our service teams was much improved, with no cases of post-traumatic stress disorder. This improvement is largely due to the changes instituted last year, when we dropped the word ‘rescue’ from our title and adopted a policy of only responding to calls where no injury was involved.

All companies have to evolve to meet the changing demands of its customers and, in our case, this meant responding to the numerous mobile phone calls from people whose day out on the fells might otherwise be spoilt by some minor inconvenience. To enable this, it was necessary to eliminate the resource-expensive and dangerous call-outs to seriously injured people. Scores of people are injured on football pitches every weekend and they all call on NHS ambulances. Why should it be different for walkers and climbers in Cumbria? The NHS receives billions of pounds of government money; the CMS receives nothing.

The morale of the CMS teams is much better. The strain of coping with 28 deaths and 415 serious injuries (as in the previous year) should not be underestimated. Our men and women are delighted to have achieved a 96% success rate this year, and look forward to helping in any way required in the future. It should perhaps be emphasised that the teams still assist people who are lost on the fells, as these generally provide an enjoyable and challenging outing.