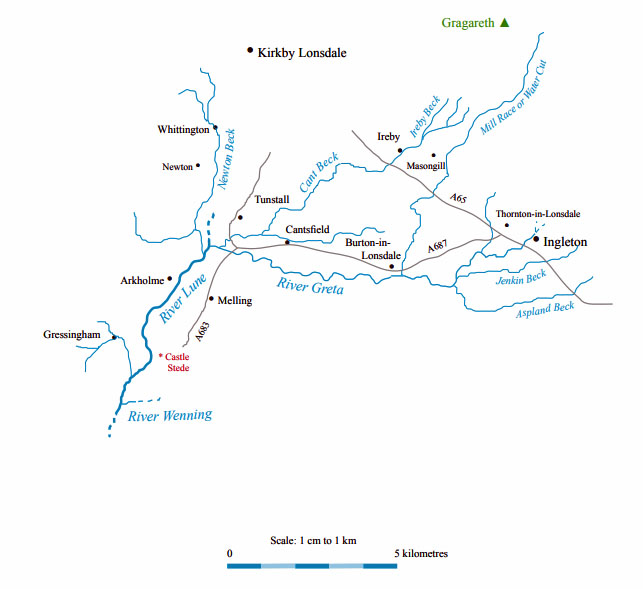

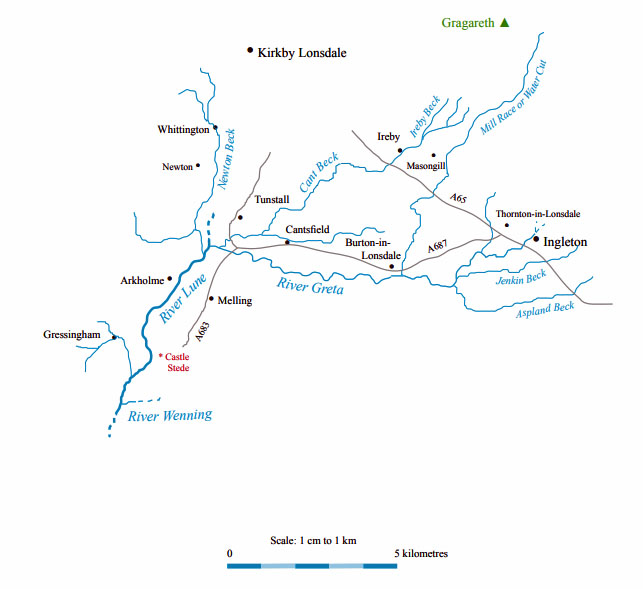

The Land of the Lune

Chapter 9: Gretadale and a little more Lunesdale

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Greta Headwaters)

The Next Chapter (The Wenning Headwaters)

Barn near Burton-in-Lonsdale

The Greta from Kingsdale Beck

Chapel Beck and Kingsdale Beck (or the Rivers

Twiss and Doe, or vice versa) merge to form the

Greta in the middle of Ingleton. Ingleton is always

thought of as part of the Yorkshire Dales although it is

in fact carefully excluded from the National Park, whose

boundary detours around the northern outskirts. Perhaps

the boundary makers agreed with the afore-mentioned

Thos Johnson who, writing of the church in 1872, said

that it “partakes of the character of the houses, being a

miserable, slap-dashed building, without one redeeming

feature.”

No writer would dare to be so offensive today but

even so it cannot be denied that Ingleton has more of

an industrial nature than places we’ve visited earlier.

Apart from the tourist industry, which dominates today,

there is still quarrying nearby, although on a lesser scale

than previously, and an industrial estate, close to the site

of the old Ingleton Colliery. In 2004 a monument was

erected near the A65 to help ensure that Ingleton’s coal

mining history is not forgotten. Small-scale coal mining,

as in Dentdale and Barbondale, existed here since the

17th century, although the seams were of poor quality

and thin, as indicated by their being called the ‘four

feet’ and ‘six feet’ seams. Numerous pits are shown on

the OS map, all marked as disused, which they became

once the railways made local coal mining uneconomic.

In 1913, however, a ‘ten feet’ seam was found deeper

underground (quite why anyone went to the trouble of

looking is unclear). The Ingleton Colliery operated until

1936, employing up to 900 people. There is no sign of

the colliery now but it is not inconceivable that, with

new technologies and changing energy policies, coal

mining will return to the region.

Left: Ingleton Viaduct, where Kingsdale Beck joins Chapel Beck to become the Greta

Left: Ingleton Viaduct, where Kingsdale Beck joins Chapel Beck to become the Greta

The Greta passes under the Ingleton Viaduct (for

the Lowgill-Clapham line) of eleven arches nearly

30m high. It is here that the ‘failure of railway politics’

mentioned in Chapter 3 was most manifest. Approval for

such a viaduct was granted in 1846 but dithering and

disagreements between the companies involved delayed

its building until 1861. Then the animosity between the

Midland Railway and the London and North Western

Railway led them to build two railway stations, the

former’s east of the viaduct and the latter’s to the west.

Through passengers were required to disembark and

transport themselves and their luggage between the two

stations. To maximise inconvenience the companies

ensured that the timetables did not mesh. (And we

complain about the modern rail system.)

Tourists from the industrial cities of the north

heading for the Ingleton Waterfalls disembarked at the

station to the east (where the information centre now is)

and were led by guides to the start of the walk, averting

eyes from the slap-dashed church, at least until 1886

when St Mary’s was rebuilt, retaining the old tower.

Inside the church there’s an interesting 12th century

font with carvings of gospel scenes. Ingleton is ancient,

appearing as Inglestune in the Domesday Book, but,

as Thos Johnson warns us, there are few old buildings

of interest. Around the viaduct and the entrance to the

waterfall walk, the main streets are lined with cafés and

shops and in summer the pavements are jostling with the

booted backpacked brigade.

The regions to the east and west of Ingleton drain to

the Greta, from below Tow Scar by becks flowing through

Thornton-in-Lonsdale and from Ingleborough Common,

south of Ingleborough, by Jenkin Beck and Aspland

Beck. Thornton-in-Lonsdale is the place furthest from

the Lune to acknowledge in its name an association with

it. A website for its Marton Arms says that “together with

historic St Oswald’s Church, they form the charming

hamlet of Thornton-in-Lonsdale.” There is a little more

to Thornton-in-Lonsdale than the pub and church, but

not much. The church is surprisingly large for such a

location and has a distinctive pyramid atop its tower. It

was rebuilt in 1933 after being burned down in a blizzard,

which sounds an event worth seeing.

Above Thornton-in-Lonsdale, on the road to the

radio station, there is an unusually smart barn. If you

peer through its windows, you will see its even more

unusual contents - a red sandstone arch. The explanation?

What else could it be but another Andy Goldsworthy

construction? This arch was built and dismantled at many

of the Goldsworthy Sheepfolds and ended up here.

Jenkin Beck forms the waterfall of Easegill Force

in a secluded gorge, falling behind a natural arch. The

beck dawdles across flat land to join the Greta 2km south

of Ingleton and it is followed shortly after by Aspland

Beck, which similarly runs uneventfully west from Cold

Cotes. Here, the bed of the Greta is adorned with multi-coloured stones, reflecting the varied geology upstream,

and the banks are heavily eroded, revealing interesting

strata.

Right: The Greta near Barnoldswick

Right: The Greta near Barnoldswick

As the Greta approaches

Burton-in-Lonsdale it passes

Waterside Pottery, which it isn’t

but which reminds us that potteries

thrived here from the early 18th

century until after the Second World

War. At one time there were fifteen

potteries. The only evidence today

is the pockmarked appearance of

the fields, from which the shale was

dug. Burton-in-Lonsdale was called

‘Black Burton’, in reference to the

earthenware produced, or to the coal

and shale used, or to the smoke from

the kilns. Or perhaps to distinguish

our Burton from the other Burton,

Burton-in-Kendal, just 12km west

in limestone country, although I can

find no record of the latter being

called ‘White Burton’.

Left: The Greta at Scaleber Woods

Left: The Greta at Scaleber Woods

On the outskirts of Burton-in-Lonsdale, the Greta is

joined by a millrace that runs from the old corn mill at

Bogg Bridge. On the 1850 OS map this bridge is called

Mill Race Bridge and the watercourse, for the 10km

from its origins on the slopes below Gragareth to the

Greta, is the “Mill Race or Water Cut”. This indicates

the considerable efforts that were made to control the

flow of water in order to power mills. In this case there

were several mills on the route of the millrace. Today

the watercourse looks entirely natural below Masongill

Fell Lane. Perhaps it was only the section to harness

Gragareth’s water that was man-made.

The beck, if we may call it that, runs past Masongill

Hall, on the east of the village of Masongill. This is a

quiet cul-de-sac, with most residences being conversions

of traditional long-houses. Masongill is responsible for

another of Loyne’s tenuous links with celebrity: in 1883

the mother of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who was then

27) moved here. Literary sleuths, who earnestly seek the

inspiration for the creator of Sherlock Holmes, know

that he regularly visited his mother and was sufficiently

part of the region to be married in 1885 at St Oswald’s

Church in Thornton-in-Lonsdale, where a certificate in

the porch names the bride as Louisa Hawkins. Some of

them are convinced that Masongill House is Baskerville

Hall, minus the hound. Others are intrigued that a

Randall Sherlock, brother of the Rev. Sherlock, vicar of

Ingleton and Bentham, was killed by lightning at Ingleton

station in 1874. I don’t know of any contemporary, local

comments on this ‘coincidence’ after Sherlock Holmes

made his appearance in A Study in Scarlet in 1887.

Right: Masongill House

Right: Masongill House

From Byber Mill the Water Cut seems not to follow

its old line but supplements Threaber Beck, which

joins Moor Gill from Westhouse near Low Threaber.

Westhouse is a distributed hamlet, with Higher, Lower

and Far Westhouse satellites. Its lodge, recently

renovated, has been given a new datestone of 1676.

The Wesleyan Chapel bears three dates, 1810, 1890 and

1912.

In 2002 over ten thousand native trees were planted

in fields north of Far Westhouse to create Edith’s Wood,

managed by the Woodland Trust. It is open to the public,

with benches from which to survey the growing trees,

with Ingleborough beyond. As the wood is a memorial,

we should remember to whom: Edith Bradshaw of

Ingleton, a teacher at Casterton School.

The Greta reaches the three-arched Burton Bridge,

with the sizable, ancient village of Burton-in-Lonsdale

on its northern slopes. It appeared as Borctune in the

Domesday Book and is the site of another motte and

bailey castle. In 1174, the de Mowbrays were ordered

to demolish the castle after an unsuccessful rebellion

against the king. A later stone castle stood until about

1350, since when the site has been abandoned. The motte,

at 10m high, is a prominent landmark, and remains of the

bailey and defensive ditches can still be seen, although

they are on private land.

Left: Ingleborough from Westhouse

Left: Ingleborough from Westhouse

Also prominent is the nearby steeple – a rarity in

Loyne – of the All Saints Church, completed in 1870.

The steeple is surfaced with wooden slats. There is also

a Methodist church, built in 1871. Like many Loyne

communities, Burton-in-Lonsdale joined in the general

questioning of the established church that began in the

17th and 18th centuries and, unlike nearby Bentham, it

came to side more with the Methodists than with the

Quakers. Maybe John Wesley’s visit in 1764 played

a part in this. So the churches are not particularly old

and neither are the houses. Most of those of any age

have been renovated, so that the neat Low Street, off

the A687, presents a parade of Smithy House, The Old

Ropery, and so on.

Motorists driving west through Burton-in-Lonsdale

will see a blue sign saying “Richard Thornton’s Church

of England Primary School” and may wonder who he is

or was. He died in 1865, having amassed a huge fortune

of over £3m from his shipping business, and left £10,000

for a school for poor children in Burton-in-Lonsdale. He

also left £1m to his nephew Thomas Thornton, who duly

had the All Saints Church built. Behind the School is

the Old Vicarage, which has a plaque in its porch that

cannot be read without trespassing (I assume that it is to

the poet Laurence Binyon).

[Update: The school closed in 2014.

The buildings and land seem to be for sale.]

Below Burton-in-Lonsdale, the south bank of the

Greta is wooded, with two of the woods, Memorial

Plantation and Greta Wood, having recently been

acquired by the Woodland Trust. The former is typical

of 19th century small plantations on land that cannot be

farmed, with pine, beech and sycamore. Greta Wood is

an older ash and oak woodland, designated an Ancient

Semi-Natural Woodland. A riverside walk follows the

Greta west for 1km – and then stops. Perhaps it is more

for fishermen, who have given names to the various

stations along Blair’s Beat: Long Pool, Tommy’s Run,

The Dubs, and Black Hole.

The Greta runs west through secluded wooded

gullies, crossing the county border and the Roman road.

At Wrayton, the Greta passes under Greeta Bridge (as it

calls itself), which has been washed away a few times

but is now in more danger from the traffic on a difficult

junction of the A683 and A687. Just before the Greta

reaches the Lune, Cant Beck joins it from the north.

Laurence Binyon is a poet from whom, if not of whom,

everybody will have heard. He wrote the words intoned at

Remembrance Day events:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

The words are part of For the Fallen, which he wrote in

September 1914.

However, Burton-in-Lonsdale’s claim to Laurence

Binyon is a little weak. He was born in Lancaster in 1869,

moving a year later to Burton-in-Lonsdale, where his father

had been appointed the first vicar of All Saints Church. But

in 1874 the family left for Chelmsford. Later, working at

the British Museum, he became an authority on oriental

art.

We might imagine that the brief time in Burton-in-Lonsdale made little impression upon him but for his own

recollections of his first memories, which were of views

of Ingleborough from the vicarage windows. Ingleborough

inspired his poem Inheritance, which began “To a bare

blue hill” and ended “Beautiful, dark and solitary, the first

of England that spoke to me.”

Cant Beck

Cant Beck is a surprisingly modest beck considering

that it drains the broad parishes of Ireby, Cantsfield

and Tunstall between Leck Beck and the Greta. It loses

the momentum gained in flowing off Ireby Fell, as Ireby

Beck, in a sluggish meander across gently undulating

pastures to Tunstall.

Ireby Beck begins life uncertainly on the southern

slopes below Gragareth, hovering around the county

border and seeming to disappear into various potholes.

The most impressive on the surface is Marble Steps Pot,

which is enclosed within the only cluster of trees on Ireby

Fell. It drops 130m. Along the line of the beck, 400m

south, is Low Douk Cave and across the county border

is Ireby Fell Cavern, a large depression with at least two

holes into which water disappears and one hole, a pipe

cemented into place (is planning permission needed for

these mutilations?), into which potholers disappear -

and in some numbers, it would seem, as a group of 25

of them needed rescuing after becoming trapped in the

cavern by heavy rain in October 2008.

I have been carefully vague in the preceding

paragraph because I read that, contrary to superficial

appearance on the map, the water falling into these holes

does not join Ireby Beck at all. The water in Marble

Steps resurges at Keld Head in Kingsdale; that of Ireby

Fell Cavern at Leck Beck Head (probably). Of course,

flows may have differed in the past and may differ in the

future. I leave this all to experts – as far as fell walkers are

concerned, the potholes mentioned can be conveniently

viewed together, above the head of Ireby Beck.

Once Ireby Beck is incontrovertibly established it

heads past some unnatural-looking mounds on the fell

(old diggings or homesteads?), by Over Hall, a tower

house dated 1687 and recently smartened up, with a

cairn-like structure in the drive, towards the village

of Ireby. As a rule of thumb, any village with a beck

flowing through its centre is at ease with itself. It soothes

and adds a timeless quality. In Ireby, the old-style red

telephone box, the only public amenity, enhances this

feeling. The houses, some of the 17th century, have been

tastefully renovated and given countrified names – all

very nice but perhaps without the character to detain a

visitor.

The fields west of Ireby Hall Farm form pleasant

and peaceful farming country, with fine views of

Ingleborough and Leck Fell. The Roman road that we

have been following cuts across here, but you would

not notice it on the ground without being told. Cowdber

Farm is so isolated that it feels it needs to put a “you are

nearly there” sign on the track to it. But the quietness

has its benefits: in the plantation near Churchfield House

is the largest heronry in Loyne. Southeast of Cowdber

is Collingholme, which promotes the good name of

the region through its Lune Valley Hampers business,

supplying luxury goods from locally produced food.

Most farms in the region have been converted, partially

or wholly, into homes for holidaymakers. Laithbutts

has gone further: it provides a home for holidaymakers’

homes. If you wish to put your caravan into storage,

there are large barns for it at Laithbutts.

To the south, Cantsfield is a small community on

the A687. The rather fine Cantsfield House, dating back

to the 16th century or earlier, has an oddly appealing

asymmetric frontage that was built by the Tatham family

in the early 18th century.

A visitor’s impression of a place can be unfair. I

noticed a sign saying “This bridleway is over private

land and is for the sole purpose of making a journey

to Tunstall and Tunstall Church. It is not a dog loo.

Please keep out unless you intend to complete the full

journey.” The map says that this is a public bridleway.

It runs through land for cows, horses and sheep and

at Abbotson’s Farm I had just plodded through their

contribution (much more substantial than a dog’s) to the

countryside aroma. And why must I complete the full

journey and not turn back?

Right: St John the Baptist Church, Tunstall

Right: St John the Baptist Church, Tunstall

As it happens, I had no wish to return to Cantsfield.

I pressed on to Tunstall’s St John the Baptist Church,

on the site of a chapel recorded in the Domesday Book.

It escaped the 19th century renovations that ‘improved’

most Loyne churches and as a result is mainly of the

15th century, with some parts thought to be pre-Norman.

A Roman votive stone from the Over Burrow fort was

built into an eastern window during a 1907 restoration.

Despite all its merits the church is best known for the fact

that some girls used to come here in 1824. The Brontë

sisters ate their packed lunches here and it became the

Brocklebridge Church of Charlotte’s Jane Eyre.

Tunstall itself is 1km to the west, past the Old

School House of 1753. The old Post Office (which

it no longer is) bears a date “circa 1640”, which is

refreshingly honest and a warning to treat other dates (of

which there are several in Tunstall) with some suspicion.

Especially, perhaps, Marmaduke House, with a plaque

“Sir Marmaduke Tunstall 1506-57”, which I take to

be the date of Sir Marmaduke, not the house. As this

indicates, we are nearing the historic Tunstall family

home, Thurland Castle, by which Cant Beck flows.

Thurland Castle is open to the public only in the sense

that if you have half a million or so to spare you can buy

a flat and live in it – which is a shame for Loyne is short

of castles with pedigree. In Saxton’s map of 1579, often

regarded as the first map of England, Thurland Castle is

one of only four places in Loyne to be shown, the others

being Lancaster, Kirkby Lonsdale and Hornby Castle.

Sir Thomas Tunstall, knighted at Agincourt, was

granted a royal licence to fortify the site in 1402. The

most famous of the Tunstalls were Cuthbert, who became

Bishop of Durham from 1530 to 1559, and Sir Brian,

who was slain at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513

– the ‘stainless knight’ described in Scott’s Marmion:

“Tunstall lies dead upon the field, His life-blood stains

the spotless shield”.

The Tunstalls sold the castle in 1605 to the

Girlingtons and they were the owners when it was razed

to the ground during the Civil War. It was restored in the

old style in 1809 and in the 1860s was owned by Major

North North. No, that is not a misprint: he was born

North Burton and assumed the surname of North when

he succeeded to the estate of Richard Toulmin North, his

great-uncle.

The castle was rebuilt again in the 1880s after a fire.

It has, no doubt, been tastefully renovated for the tenants

of the twelve flats created from the castle and adjacent

stables. The castle can now only be glimpsed from afar

through trees. It consists of a circuit of walls and towers,

enclosed in a moat, with a drawbridge into a courtyard

but with no keep.

The estate agents try to give the castle some prestige

by asserting that “in 1809 the architect James Wyatt,

who was working on Windsor Castle at the time, was

commissioned to restore the castle.” James Wyatt (1746-1813) was the principal architect of the day and was

notorious for taking on more commissions than he could

manage. His nephew Jeffry Wyatt (1766-1840), later

Wyattville, was probably more involved with Thurland

Castle and it was he who later (1824 to 1836) carried out

a major renovation of Windsor Castle. Thurland Castle

does not feature highly in either architect’s portfolio.

A short distance after Cant Beck has joined, the

Greta reaches the Lune, which it enters in a straightened

westerly channel, as old maps show the Greta entering

the Lune in a long curve to the south of its present course.

The Greta joins the Lune

Then, unnoticed (almost), Newton Beck sidles into the

Lune from the west.

Newton Beck

Like most becks on the west bank of the Lune,

Newton Beck begins in desultory fashion among

the low, rolling hills and never really gets going. It

runs alongside the Lune for 5km from High Biggins,

just south of Kirkby Lonsdale. At High Biggins there

are, apart from the Old Hall, three halls of strikingly

different architecture: Biggins Hall Farm, a black-and-white, seemingly half-timbered house with a red-tiled

roof; Lonsdale Hall, a white Georgian mansion; Sellet

Hall, a more vernacular stone building.

In 2006 the farm was sold in six lots (a subsequent

proposal to use some buildings for storage was rejected);

Lonsdale Hall houses a management consultancy; Sellet

Hall is the home of a forestry management company.

Loyne has no stately mansions like, say, Chatsworth

House, but it has many halls for the landed gentry of

the Middle Ages and later. The story of these halls, and

the attempts, of mixed success, to find them a role in the

21st century, would make a fascinating contribution to

the social history of the region.

Sellet Hall Beck and Pinfold Beck converge in the

village of Whittington, near an even more impressive

hall, Whittington Hall. It was designed in 1831 for the

Lancaster MP, Thomas Greene, by George Webster, four

of whose halls we have already met: Ingmire, Rigmaden,

Whelprigg and Underley. It is similarly in the Elizabethan

revival style, in this case with medieval features, such as

a peel tower. The best view of Whittington Hall is to be

had on the path north from Outfield, where a walk is in

silence apart from the screech of disturbed pheasants.

The hall is seen, from a distance admittedly, with the

Howgills and Middleton Fell behind.

East of the Hall is St Michael’s Church, which was

probably founded as the chapel within

the bailey of a motte and bailey castle.

The tower, of 1600 or so, is the oldest

part of the present church, which was

rebuilt in 1875. In the graveyard is a

headstone that reads “In memory of

Edward Baines of Whittington who

died of Asiatic cholera on board the ship

Brutus midway to America and was

buried at sea June 3rd 1832”. Historians

of Lancashire will be familiar with

Baines’s Gazetteer, that is, The History,

Directory and Gazetteer of the County

Palatine of Lancaster, written by Edward Baines in 1824

– which contains details of Whittington’s illustrious

history. They are, however, not the same Edward Baines

and, as far as I can determine, were unrelated.

Left: William Sturgeon plaque

Left: William Sturgeon plaque

According to Baines (of the Gazetteer), before the

Norman Conquest, Tostig, Earl of Northumbria and

brother of Harold II, owned six carucates (over 2 sq km)

in Whittington, which was regarded as the capital of the

region between Sedbergh, Ingleton and Gressingham.

Tostig owned a further 20 sq km within this region. After

Tostig’s death at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, the estate

was broken up and by 1090 Whittington had passed into

the hands of Roger of Poitou, who eventually owned all

of what was to become Lancashire. At Baines’s time,

Whittington was one of five parishes in the deanery of

Lonsdale (the others being Claughton, Melling, Tatham

and Tunstall).

Some of this heritage may be appreciated by a

stroll around the village, where several houses bear 17th

century dates. The Manor House and T’Owd Rose Tree,

both 1658, share the prize for oldest house (subject to

appeal). Croft House in Main Street was the birthplace

in 1783 of William Sturgeon. As with other Loyne

notables, the response is probably: Who?

His plaque in Kirkby Lonsdale church predicted that

“His name will be perpetuated as long as the science he

cherished continues to exist”. The science of electricity

has flourished but William Sturgeon has been almost

forgotten. As a boy he helped his father poach salmon

from the Lune. He was then apprenticed to a cobbler

in Old Hutton, near Kirkby Lonsdale, but escaped in

1802 by enlisting in the army where he taught himself

enough science to be able to build the first practical

electromagnet in 1825 and to design the first rotary

electric motor. Perhaps his untutored, practical, blunt,

northern ways led to his neglect by the

gentlemen scientists of the day.

The becks merge to form Newton

Beck beyond Newton, which, like

Whittington, is old enough to be

in the Domesday Book. The beck

eventually makes it way past the flood

embankment to join the Lune near

Higher Broomfield. The finger of land

beyond the footbridge over Newton

Beck is not publicly accessible and

is therefore a haven for birds, such as

snipe.

The Lune from Newton Beck ...

The Lune passes under the bridge for the Wennington-Carnforth railway line. To be precise, it passes

through the second of the six arches, which, although

the largest, seems not large enough for the Lune to be

channelled through. Is there an explanation?

Right: The Melling Viaduct

Right: The Melling Viaduct

There are, 500m east, a further sixteen arches. The

1847 OS map shows the Lune flowing there, with the

present course of the Lune, by Arkholme’s Chapel Hill,

then being a backwater marked as “old Lune”, indicating

that before 1847 the Lune had followed its present path.

Moreover, there is a second “old Lune” marked, near

Melling to the east, indicating a third Lune channel. In

short, the Lune has changed course frequently within

relatively recent times. It is thought that when the bridge

was built in 1867 the embankment between the two

sets of arches was on an island in the Lune. Today the

Melling Viaduct, which would form the longest bridge

across the Lune if only the Lune were still to run under

it, stands over ponds in green fields.

The railway line was built to link Furness Railway’s

eastern station at Carnforth with Midland Railway’s

‘little North Western’ line from Leeds to Lancaster,

and hence to link the growing port of Barrow with the

industries of Yorkshire. They must have been keen to

achieve this as the costs of such a long bridge and the

1km tunnel between Melling and Wennington must have

been high. When the Wennington-Lancaster line closed

in 1966, the Wennington-Carnforth line became part of

the Leeds-Lancaster route.

Left: The old Arkholme railway station

Left: The old Arkholme railway station

There were stations at both Arkholme and Melling

but they were closed in 1960. There is no footpath on

the railway line, the ferry across the Lune ended service

in the 1940s, and the ford has fallen into disuse, leaving

the two villages, only 1km apart, more separated now

than ever.

By fortune or foresight, the road in Arkholme runs

from the old ferry (from the Ferryman’s Cottage, in fact)

west for 1km to meet the Kirkby Lonsdale road at right

angles and is therefore a peaceful cul-de-sac. In summer,

colourful gardens face the road and there is a prettiness

and cheeriness, due to the relative absence of traffic. The

houses are strung out higgledy-piggledy, no two alike,

some old (17th century), some new (21st century).

Most of the older houses have names indicating

their previous lives, although I noticed none that refer

to the industry for which Arkholme was best known,

the making of baskets, from about 1700 to 1950. This

activity was typical of many Loyne industries, being

based on some local resource (here, osiers in the

Lune floodplain), intended to meet local needs (of, for

example, potato growers in Fylde), and passed on as a

family trade, but then succumbing to competition from

larger, more commercial ventures,

especially after the advent of the

railways.

On the other bank, its sister

Melling lies mainly along the busy

and narrow A683 and as a result

its doors and windows are shut, its

gardens are away from the road,

and people do not linger by the

noisy and dangerous traffic. Within

Melling, Green Close Studios,

which opened in 1997, has focussed

on locally-based art activities and

in 2009 initiated the Bowland Arts

Festival.

The future of Melling Hall,

an 18th century manor house,

more recently a hotel and now

a listed building, has been the

subject of a planning debate that

is an interesting example of the

difficulties of conservation policies. The building is a key

part of the Melling Conservation Area, and the Lancaster

District policy is that no pub or hotel will be converted

to residential use unless it can be demonstrated to be no

longer viable, even if, as in this case, it was originally

a residence. No buyer could be found to sustain it as a

hotel and, after some controversy, it has been converted

into flats.

[Update: The future of Melling Hall has continued to provide

confusing entertainment. Melling Manor, the old east wing of Melling Hall and valued at £845,000, was

sold by raffle in 2017.

(I think I was wrong to say that the Hall had been converted into flats.) The present Melling

Hall, valued at £930,000, was to be raffled in 2020 but not enough tickets were sold.

I suppose that means that Melling Hall is still for sale.]

Arkholme and Melling are listed in the Domesday

Book as Ergune and Mellinge, respectively. The parish

boundary between them lies near Melling, where the

Lune once flowed. Both Arkholme and Melling had

their motte and bailey castles and in

both cases a church has been built,

as at Whittington, within the bailey.

Arkholme’s St John the Baptist

Church is tucked below, almost

into, the motte, which is 30m in

diameter. Melling’s St Wilfrid’s is a

larger church, with a long nave and

square tower, and is a Biological

Heritage Site because of the lichens

on its gravestones. The Melling

motte is now a feature in the garden

of the Old Vicarage.

Right: St Wilfrid’s Church, Melling

Right: St Wilfrid’s Church, Melling

The Arkholme motte is close to

the Lune Valley Ramble, which the

Lune has accompanied from Kirkby

Lonsdale, and below Arkholme the

Ramble shares footsteps with the

Lunesdale Walk, a name that is even

more of an exaggeration than the

Ramble since its 59km cover only

6km of the Lune. The walk traces

an elaborate figure of eight route

from Carnforth to Roeburndale.

The Lune runs by flat, green

pastures on the east, where the old

Lune has created many ditches and

where enormous logs have been left

stranded by floods. Bank erosion

continues apace, and the Lune

shifts between various channels,

running by pebble beaches and

new islands. To the west, there are

gentle hills, on the horizon of which

can be seen the turrets of Storrs

Hall, which was rebuilt in 1850,

and from which minor tributaries

such as Bains Beck and Thrush Gill

enter the Lune. The hills are not

high, reaching only 142m at Cragg

Lot, but nevertheless there is an

application to put five 125m wind

turbines on them. This proposal is ominous for

the Lune valley, for if turbines are built in such a

location then no field and no view within the Lune

valley is safe.

Left: Erosion of the Lune bank near Arkholme

Left: Erosion of the Lune bank near Arkholme

The Lune reaches Loyn Bridge, which was

built in 1684 or before – it is known that an earlier

bridge was reported as dangerous in 1591. The

bridge is built of sandstone blocks and has three

arches, the outer ones of 16m and the inner of

19m. The piers have pointed cutwaters that provide

alcoves on the 4m-wide carriageway. The bridge

provides the only vehicular crossing of the Lune

for about 8km in either direction. It is clearly sturdy

enough to withstand Lune floods but no doubt its

builders knew that when the Lune is high it takes a

short cut across the fields to the west, as damage to

the hedgerows shows.

Above Loyn Bridge to the east is Castle

Stede, the remains of a motte and bailey castle

(our eighth, if you are counting). When Castle

Stede was abandoned as a castle, later buildings

did not engulf it, so the original structures are well

preserved. We can see the 15m-high motte and the bailey,

with its defensive ramparts and ditch, and appreciate the

strategic position overlooking the Lune valley. Strictly,

it is off the public footpath but it is tempting to wander

over the causeway (probably where the original entrance

was) into the bailey and transport oneself back to the 12th

century by imagining the bustle of activity – kitchens,

stables, maybe a chapel – below the lord’s hall on the

motte.

At Loyn Bridge we enter for the first time the

Forest of Bowland Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty,

although we are still some distance from typical Bowland

country. The ambivalent regard for the Bowland region

is indicated by the inclusion of “Bowland and the Lune

Valley” (where they mean the lower Lune valley) as one

of twelve projects within the Culture 2000 European

Pathways to Cultural Landscapes programme, funded by

the European Union. This sounds like an honour indeed

– until we read that the project is “dedicated to ‘marginal’

landscapes, border regions and landscapes whose image

is one of poverty and historical insignificance”.

Left: Loyn Bridge

Left: Loyn Bridge

Right: The Norman doorway of Gressingham church

The Lune passes below Priory Farm, which is on

the site of an old Premonstratensian priory, that is, one

belonging to the order of ‘White Canons’ (from the

colour of their habit) founded at Prémontré in France.

Shortly after, the small Gressingham Beck enters from

the west. This beck gathers the waters from the rolling

green hinterland beyond the western ridge and, with

High Dam Beck (which runs from the ‘high dam’ that

used to power the mill), channels them through the

ancient village of Gressingham.

Gressingham is another of Earl Tostig’s holdings

that was listed in the Domesday Book (as Ghersinctune)

but nothing much has happened here since. The small

triangle of homesteads and the line of dwellings by the

beck are quietly attractive, as is the church with its 12th

century arch in the doorway, but the village does little

to draw attention to itself. As far as I am aware, it does

not even claim an association with the one thing that

makes its name famous, the Gressingham Duck, which

features on the best menus. However, assiduous research

(I asked the producers of the duck) revealed that “the

chap who first bred the duck is called Peter Dodd, [who]

lived in the village of Gressingham in Lancashire … the

breeding stock [was moved to] Suffolk in 1990”.

Next, the River Wenning joins the Lune from the

east.

The Forest of Bowland was designated an Area of

Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1964 and its 800

sq km make it the 11th largest of the 41 AONBs in England

and Wales. An AONB designation recognises a region’s

scenic qualities and implies a commitment to conserve

its flora, fauna and landscape features, consistent with the

needs of residents. Only the northern third of Bowland lies

within Loyne. The remainder, reached by the two bleak

roads to Slaidburn or through the Trough of Bowland,

drains to the Wyre or Ribble.

The Forest of Bowland is a forest in the historical sense

of an unenclosed, outlying region of little use except for

hunting. Bowland was originally a Royal Forest, although

no sovereign is known to have hunted here. However, Henry

VI was himself hunted, when in 1465, during the Wars

of the Roses, he hid in Bolton-by-Bowland. Traditional

hunting has long gone, to be replaced by grouse shooting,

mainly on land owned by England’s richest aristocrat, the

Duke of Westminster. Until the Countryside and Rights of

Way Act took effect in 2004 (launched in Bowland), this

was England’s largest area without public access.

Lower Bowland consists of rolling green pastures

with picturesque grey stone buildings. The upland areas are

of millstone grit, with thin layers of sandstone and shale

on the slopes, giving rise to open and wild upland areas

of blanket bog and heather moorland that are incised by

fast becks to form steep cloughs and wooded valleys. The

wilderness areas of Bowland remain largely unspoilt by

exploitation, with the works of the water authorities and

the Forestry Commission lying mainly outside Loyne. The

higher fells have been maintained in a relatively natural

state for the sheep and grouse and, since 2004, humans.

The Introduction

The Previous Chapter (The Greta Headwaters)

The Next Chapter (The Wenning Headwaters)

© John Self

Left: Ingleton Viaduct, where Kingsdale Beck joins Chapel Beck to become the Greta

Left: Ingleton Viaduct, where Kingsdale Beck joins Chapel Beck to become the Greta

Right: The Greta near Barnoldswick

Right: The Greta near Barnoldswick

Left: The Greta at Scaleber Woods

Left: The Greta at Scaleber Woods

Right: Masongill House

Right: Masongill House

Left: Ingleborough from Westhouse

Left: Ingleborough from Westhouse

Right: St John the Baptist Church, Tunstall

Right: St John the Baptist Church, Tunstall

Left: William Sturgeon plaque

Left: William Sturgeon plaque

Right: The Melling Viaduct

Right: The Melling Viaduct

Left: The old Arkholme railway station

Left: The old Arkholme railway station

Right: St Wilfrid’s Church, Melling

Right: St Wilfrid’s Church, Melling

Left: Erosion of the Lune bank near Arkholme

Left: Erosion of the Lune bank near Arkholme

Left: Loyn Bridge

Left: Loyn Bridge