Ramblings

Saunterings

Ramblings: about North-West England

Ramblings is a set of articles about North-West England, of unknown authorship and

indeterminate date, believed to have been written for amusement on rainy days,

which are not unknown in North-West England.

35. More Books for Offcomers

Here are two more books that may help offcomers become assimilated in the fine county of Cumbria:

Cumbrian Weather by Jeremy Winder

Cumbrian Weather: A Psychosociohistorical Study, by Jeremy Winder

(Keswickian Press, £24.99), 378 pages with innumerable tables,

charts, diagrams, figures, photographs and maps (and quite a few

words).

Gaining admission to the fine county of Cumbria is only the

first step on the long and treacherous road to assimilation. The

natives are rightly wary of aliens from places such as Letchworth

and Worksop. It requires extensive study and careful application to

begin to gain acceptance. This in-depth monograph on Cumbrian

weather should prove more than useful.

Gaining admission to the fine county of Cumbria is only the

first step on the long and treacherous road to assimilation. The

natives are rightly wary of aliens from places such as Letchworth

and Worksop. It requires extensive study and careful application to

begin to gain acceptance. This in-depth monograph on Cumbrian

weather should prove more than useful.

Cumbria has 35% more weather than any other English county

and the natives are proud of all of it. In your first two or three

decades in the county do not offend the natives by pretending more

familiarity with the weather than you have. Do not, for example,

refer to the Great Deluge of 1966 because the natives will know

that you did not directly experience it: they will dismiss you as an

ingratiating ingrate. Just say “a bit nippy today” or “at least it’s

not raining as hard as yesterday” or “they say it’ll stop snowing

tomorrow”, as appropriate.

Eventually, however, you will be able to employ the

voluminous facts provided by Cumbrian Weather. For example, you

might manage something like the following:

Neighbour: A bit wet today, Jim.

You: Sure is, but not as wet as forty years ago today.

Neighbour: Really? What happened then?

You: That was the day of the Great Deluge of 1966, when five

inches of rain fell in half an hour and old Mrs Hargreaves at

High Dudgeon had two barns washed away.

Neighbour: Oh, yes. I remember. And Fred Brisket’s horse was

buried under an avalanche of mud.

And so on and so forth. Of course, you can only carry this

off if you’ve been around long enough for your neighbour to have

forgotten that you weren’t here for the Great Deluge.

Emboldened by this triumph, you can then move on to the

really fascinating parts of Jeremy Winder’s study of the impact of

the weather on Cumbrian life and psyche. His general point is that,

for Cumbrians, weather does not just happen: it has a meaning and

a purpose. You can integrate this philosophical insight into your

exchanges. For example:

Neighbour: Not doing too well in the Test Match, eh, Jim.

Neighbour: Not doing too well in the Test Match, eh, Jim.

You: Aye. And it’s all our fault.

Neighbour: Our fault? What do you mean?

You: Well, there’s never been a Cumbrian test cricketer.

Neighbour: Really? Why’s that then?

You: Partly because there are only three places flat enough for a

cricket pitch. But really because of the weather. Did you know

that in summer, in the hours we could be playing cricket, it is

raining 43% of the time. And when it’s not raining the pitch

is still waterlogged for another 26% of the time. So really it’s

not worth the bother of putting the pads on. Mind you, if we

Cumbrians had stood in a field all day long we wouldn’t have

got on with more important things, such as ...

And on and on and on. I have paraphrased this monologue

in order to fit it within the confines of this column, but, after a

thorough study of Jeremy Winder’s book, you could easily extend it

to last an hour or two. Take care, however, for although Cumbrians

love their weather they hate a smart-arse. But at least at the end of

it you will feel like a real Cumbrian, especially if it is raining and

you are soaked through.

The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane

The Wild Places, by Robert Macfarlane (Granta Books, £18.99), 340

pages with 16 black-and-white photographs and 1 upside-down map.

The Wild Places, by Robert Macfarlane (Granta Books, £18.99), 340

pages with 16 black-and-white photographs and 1 upside-down map.

This book should help offcomers to develop an appreciation

of the wilder regions of the Lake District. Following the tradition

of Homer’s Odyssey, the Norse sagas, Cervantes’s Don Quixote and

Lear’s The Owl and the Pussycat, The Wild Places describes a series of

fantastical adventures during which our hero (the author) muses

upon wilderness and the nature of nature.

The narrative takes the form of mythological outings to actual

wild areas of the British Isles, from the peak of Ben Hope to the salt-marshes

of Dengie. Chapter 10 is of particular interest to would-be

Cumbrians, being based upon the standard walk from Buttermere

to Red Pike and High Crag. Of course, for our hero the standard

walk would not be wild enough. He must walk at night, alone, and

in a blizzard.

The metaphorical nature of the expedition is first emphasised

by the surreal discovery of a trail of one-inch high red pinnacles

sticking from the snow. These, we are told, are formed by drops

of blood freezing in the snow, which has then been blown away.

This, of course, is allegorical: it is intended to convey the mortality

of man, who may, with fortitude such as that of our hero, rise above

the severest conditions.

The metaphorical nature of the expedition is first emphasised

by the surreal discovery of a trail of one-inch high red pinnacles

sticking from the snow. These, we are told, are formed by drops

of blood freezing in the snow, which has then been blown away.

This, of course, is allegorical: it is intended to convey the mortality

of man, who may, with fortitude such as that of our hero, rise above

the severest conditions.

The explanation for this imaginary phenomenon is nonetheless

intriguing. Nowadays, whenever it snows, I take my wife for a walk

and, as we stroll along, I prod her with a fork (a fork, I find, is better

than a knife as it produces four drops not just one). I then return

along the path at three-hourly intervals, hoping to find little red

pinnacles. So far, I have only seen rather unpleasant red blotches.

This may be because my wife has donated so much blood that what

she has left is too dilute to stand firm.

To return to the narrative of Chapter 10, our hero continues his

walk up Red Pike only to find that the blizzard is so strong that he

cannot distinguish land from sky or even stand up. So he decides

to have a nap upon a frozen tarn. Now, for the benefit of offcomers,

I must emphasise that this is a fantasy. Survival handbooks do not

recommend going for a lie-down on a frozen tarn if caught in a

blizzard. Anyone familiar with the reminiscences of Silas Jessop

(see Rambling 3) will know that this is fraught with danger.

Our hero, however, sleeps “for some hours” and on awaking

finds that he has melted a sarcophagus in the ice. In reality, he

would awake to find rigor mortis had set in.

This, however, is not reality. Our hero now finds that the

blizzard has miraculously abated. He walks towards High Crag to

find that he has moonlit views of winter hills all around him. He

reflects at length on the deeper optical sensitivity and the profound

insight that this experience affords, with extra wildness conferred

on a metallic landscape.

However, in a slight inconsistency in the tale, when he reaches

High Crag he decides to pitch his bivouac and have another sleep.

Now, walkers in inferior day-time conditions would think little of

continuing over Haystacks and Fleetwith Pike and maybe even

around to Robinson. But our indolent hero, after only a one hour

walk from Red Pike, has apparently had enough of the unique

experience that he has just eulogised.

He awakes before dawn and makes a seat in the snow to watch

the sun rise. Of course, it is not an overwhelming surprise when

the sun does appear but a sunrise invariably stimulates those of a

poetic bent, like our hero, to an excess of romantic effusions.

That obligation over, he walks down to the lake, where there is

a bizarre episode which encapsulates the spirit of the book.

He picks up a rock and contemplates the manifold ways that

it is actually moving in the universe and the manifold forms of

radiation that are bombarding it (you can see why he walks alone).

He then purges himself of such idle thoughts by stripping off

and sitting up to his neck in icy water. This is clearly intended to

symbolise the return from wilderness to the cold reality of our tame

modern life.

After a number of such epic adventures, our hero comes to

the conclusion that it is, after all, unnecessary to indulge in such

extreme behaviour to experience true wilderness. It can be found

rather more easily in local woods and hedgerows, which I am sure

will come as a relief to offcomers.

Photos:

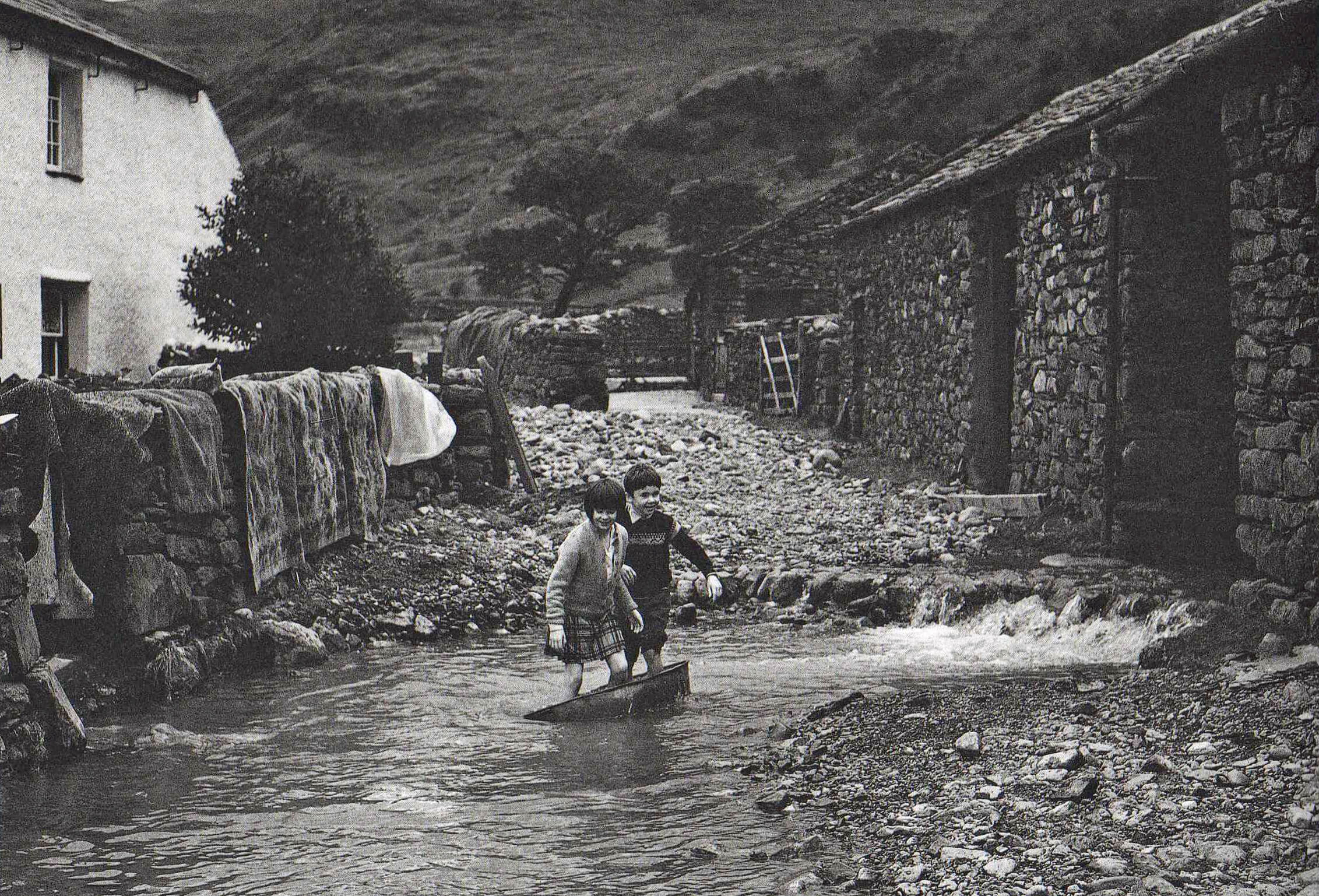

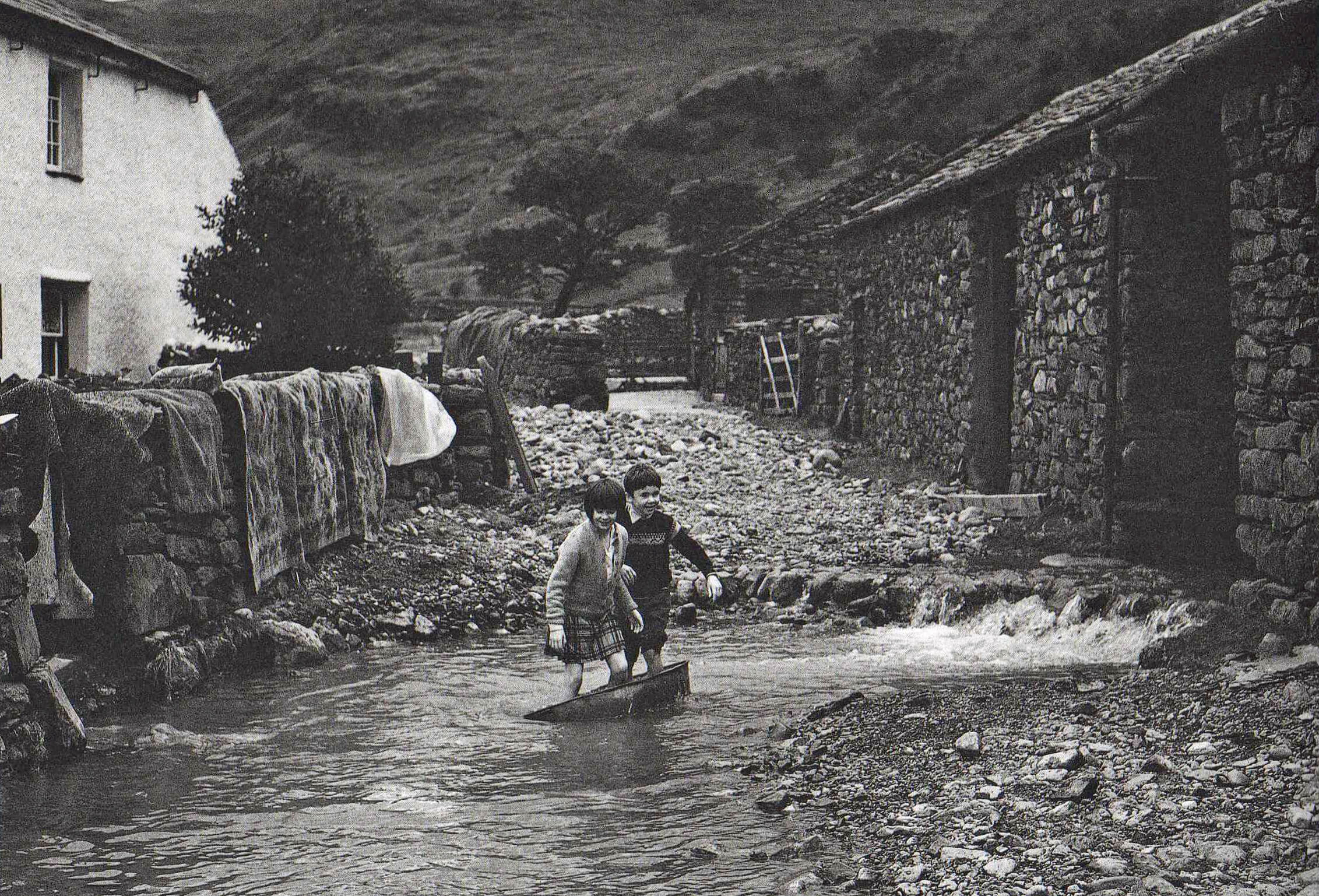

Seathwaite Farm in Borrowdale after the Great Deluge of 1966, when they

had to live upstairs for seven months while downstairs dried out.

A car that says "Kendal's professional cricketer

Ross McMillan" on its side.

The Wild Places book covers.

Bleaberry Tarn, where Macfarlane had a sleep.

Comments:

• I think you are confused about the two

book covers for 'The Wild Places'. They are two different books.

The second one (the one with the mermaid) looks more enticing.

Ramblings

Saunterings

© John Self, Drakkar Press, 2024-

Top photo: Rainbow over Kisdon in Swaledale;

Bottom photo: Ullswater

Gaining admission to the fine county of Cumbria is only the

first step on the long and treacherous road to assimilation. The

natives are rightly wary of aliens from places such as Letchworth

and Worksop. It requires extensive study and careful application to

begin to gain acceptance. This in-depth monograph on Cumbrian

weather should prove more than useful.

Gaining admission to the fine county of Cumbria is only the

first step on the long and treacherous road to assimilation. The

natives are rightly wary of aliens from places such as Letchworth

and Worksop. It requires extensive study and careful application to

begin to gain acceptance. This in-depth monograph on Cumbrian

weather should prove more than useful.

Neighbour: Not doing too well in the Test Match, eh, Jim.

Neighbour: Not doing too well in the Test Match, eh, Jim.

The Wild Places, by Robert Macfarlane (Granta Books, £18.99), 340

pages with 16 black-and-white photographs and 1 upside-down map.

The Wild Places, by Robert Macfarlane (Granta Books, £18.99), 340

pages with 16 black-and-white photographs and 1 upside-down map.

The metaphorical nature of the expedition is first emphasised

by the surreal discovery of a trail of one-inch high red pinnacles

sticking from the snow. These, we are told, are formed by drops

of blood freezing in the snow, which has then been blown away.

This, of course, is allegorical: it is intended to convey the mortality

of man, who may, with fortitude such as that of our hero, rise above

the severest conditions.

The metaphorical nature of the expedition is first emphasised

by the surreal discovery of a trail of one-inch high red pinnacles

sticking from the snow. These, we are told, are formed by drops

of blood freezing in the snow, which has then been blown away.

This, of course, is allegorical: it is intended to convey the mortality

of man, who may, with fortitude such as that of our hero, rise above

the severest conditions.